Summary

Confucius Institutes are teaching and research centers located at colleges and universities, underwritten by the Chinese government. Since 2005, more than 100 Confucius Institutes (CIs) have opened in the United States; 103 remain in operation.

These Institutes, many offering for-credit courses in Chinese language and culture, are largely staffed and funded by an agency of the Chinese government’s Ministry of Education—the Office of Chinese Languages Council International, better known as the Hanban. The Hanban also operates similarly organized Confucius Classrooms (CCs) at 501 primary and secondary schools in the United States. These 604 educational outposts comprise a plurality of China’s 1,579 Confucius Institutes and Classrooms worldwide.

Confucius Institutes frequently attract scrutiny because of their close ties to the Chinese government. A stream of stories indicates that intellectual freedom, merit-based hiring policies, and other foundational principles of American higher education have received short shrift in Confucius Institutes.

The Hanban has shrouded Confucius Institutes in secrecy. At most Institutes, the terms of agreement are hidden. China’s leaders have not assuaged worries that the Institutes may teach political lessons that unduly favor China. In 2009, Li Changchun, then the head of propaganda for the Chinese Communist Party and a member of the party’s Politburo Standing Committee, called Confucius Institutes “an important part of China’s overseas propaganda set-up.”1

We conducted case studies at twelve Confucius Institutes—two in New Jersey and ten in New York—and asked about hiring policies, funding arrangements, contracts between the Hanban and the university, pressure on affiliated faculty members, and more. This report is the result of that investigation.

We found cause for concern in four areas.

- Intellectual freedom. Official Hanban policy requires Confucius Institutes to adhere to Chinese law, including speech codes. Chinese teachers hired, paid by, and accountable to the Chinese government face pressures to avoid sensitive topics, and American professors report pressure to self-censor.

- Transparency. Contracts between American universities and the Hanban, funding arrangements, and hiring policies for Confucius Institute staff are rarely publicly available. Some universities went to extraordinary efforts to avoid scrutiny, cancelling meetings and forbidding NAS from visiting campus.

- Entanglement. Confucius Institutes are central nodes in a complex system of relationships with China. Confucius Institutes attract full-tuition-paying Chinese students, fund scholarships for American students to study abroad, and offer other resources. Universities with financial incentives to please China find it more difficult to criticize Chinese policies.

- Soft Power. Confucius Institutes tend to present China in a positive light and to focus on anodyne aspects of Chinese culture. They avoid Chinese political history and human rights abuses, present Taiwan and Tibet as undisputed territories of China, and develop a generation of American students with selective knowledge of a major country.

We recommend that all universities close their Confucius Institutes.

If a college or university refuses to close its Confucius Institute, we recommend faculty members and administrators push for the following reforms.

- Provide transparency. Make available for easy download all memoranda of understanding, contracts, and other agreements between the university and the Hanban, or between the university and the Chinese partner institution. Annually disclose how much funding the university receives from the Hanban or the Chinese partner institution for the Confucius Institute, and disclose how much the host university contributes (separating in-kind contributions from real expenses). Disclose all trips, honors, and awards bestowed on university officials by agencies of the Chinese government.

- Ensure that all CI budgets are separate from university budgets, and that all Confucius Institute events are advertised as such. As much as possible, Confucius Institutes should be distinguished from their host institutions. Confucius Institute events should not be listed on university calendars, promoted on the university website, or used as assignments or count toward extra credit for students. The Hanban considers Confucius Institutes standalone nonprofit organizations, yet houses them in universities and benefits from the status and prestige of the university. Reduce this free-riding.

- Cease outsourcing for-credit courses to the Hanban. Ensure that Chinese language classes are taught by professors or instructors selected and paid by the university.

- Renegotiate contracts to remove constraints against “tarnishing the reputation” of the Hanban. Scholarship should be civil, but it should not be constrained by the fear of punishment for offending Chinese sensitivities.

- Formally ask the Hanban if its hiring process complies with American non-discrimination policies. Does the Hanban prioritize members of the Communist Party? Are members of Falun Gong still excluded? Is the selection based purely on merit? Ask the Hanban for a formal written answer.

- Change the wording of all contracts to clarify that legal disputes should be settled only in the jurisdiction of the host institution (in our cases, American courts). Add language specifying that in all disputes between Chinese and American law, American law takes priority. The Hanban should assume legal liability if it violates American law when operating a Confucius Institute in America.

- Require that all Confucius Institutes offer at least one public lecture or class each year on topics that are important to Chinese history but are currently neglected, such as the Tiananmen Square protests or the Dalai Lama’s views on Tibet. Ensure that these programs are fair, balanced, and free of external pressures.

- Include in orientation for every Confucius Institute teacher and Chinese director the university’s policies on academic freedom. Ensure that all teachers enjoy the same rights.

- Make the Confucius Institute director’s position a voluntary service position, with no additional pay, thereby reducing financial pressures for CI directors to cater to the Hanban’s preferences.

We also recommend that state and federal legislative bodies exercise oversight.

- Congress should open an investigation of Confucius Institutes and inquire whether American interests are jeopardized by these institutes. Congress should ask universities to turn over copies of their agreements with the Hanban and their partner Chinese universities.

- State legislatures should hold similar investigations on all public universities with a Confucius Institute in their state.

- Congress should also evaluate risks to national security. It should consider whether Confucius Institutes increase the risks of a foreign government spying or collecting sensitive information.

- Congress and state legislatures should also investigate the Chinese government’s use of Confucius Institutes to monitor, intimidate, and harass Chinese students. Congress should evaluate whether Confucius Institutes improperly curtail students’ freedom to study.

Our primary recommendation is that all American universities—and school districts—with Confucius Institutes or Classrooms should close these centers and end all contracts with the Hanban. We urge these secondary reforms as intermediary steps to protecting the integrity of American education and intellectual freedom.

Preface

“Confucius Institutes” are a project by the Chinese government to shape American attitudes towards that nation’s Communist government. The Institutes are housed at American colleges and universities, and there are currently more than one hundred of them. The name “Confucius Institute,” like almost everything else about the initiative, is misleading. Confucius Institutes have nothing to do with the ancient Chinese sage. They are ostensibly centers for teaching American students Chinese language and puff courses on Chinese arts. In reality, they are instruments of what Harvard University professor Joseph Nye calls “soft power.” That is, they attempt to persuade people towards a compliant attitude, rather than coerce conformity.

But even this is not quite exactly right. Confucius Institutes don’t overtly force their views on Americans, but behind the appearance of a friendly and inviting form of diplomacy lies a grim authoritarian reality. The Confucius Institutes are tightly managed from China by an agency of the government. They are staffed by Chinese nationals on short-term contracts. Their relations with their American hosts are governed by secret agreements enforced in Chinese courts under Chinese law. And many students from China studying in the U.S as well as faculty members believe the Institutes are centers of surveillance. There is no positive proof that the Institutes are also centers for Chinese espionage against the United States, but virtually every independent observer who has looked into them believes that to be the case.

The study that follows says nothing about that speculation, but not for lack of testimony. The author, Rachelle Peterson, spoke to numerous individuals who demanded total anonymity as the condition for saying anything. Their stories go unreported here because the body of this report presents only verifiable facts. In this preface, however, I am granting myself license to go beyond what we can fully verify. That’s because the off-the-record stories we collected were consistent in their portrayal of the Confucius Institutes as centers of threats and intimidation directed at Chinese nationals and Chinese Americans, and as cover for covert activities on the part of the Chinese government.

Possibly this is a collective illusion harbored by Chinese nationals and by Americans who hold hostile views of the Chinese Communist government. We cannot with certainty say whether the accusations are warranted. But it would be a failure on our part if we did not report the allegations, which form a forest of suspicion surrounding the castle of Confucius Institutes.

A major question that hangs over this report is why American colleges and universities lend themselves to serving as hosts for the Confucius Institutes. Are they unaware of the unsavory reputation of these instruments of “soft power” in the hands of one of America’s international adversaries? Are they naïve about the appearance of putting the credibility of their institutions at risk by making them subject to the whims of a foreign government that summarily rejects the freedom of expression and open inquiry that are bedrock principles of American higher education? Are they indifferent to the possible abuse of the rights of the Chinese students studying in the United States?

They are definitely not unaware of the unsavory reputation of Confucius Institutes. Within the world of American higher education, word has spread, and no college president could entertain an offer from the Hanban (the Chinese government body that orchestrates this effort) without finding out about the controversies that swirl around the Institutes.

The unfortunate answer to the other two questions is yes. The American colleges and universities that sign up are naïve, and they are generally indifferent to the consequences. What motivates the college administrators who accept these invitations is a combination of greed and vanity. The Hanban knows exactly how to play the contemporary American college president and his staff.

As Rachelle Peterson explains in the pages that follow, Confucius Institutes pay their way. Typically they enter into five-year contracts in which they pay their host universities a substantial annual fee. And they provide services, such as Chinese language instruction, that the host university need not pay for. It seldom stops there. The officials of the host university are invited to junkets in China where they lecture and are feted. And the Hanban supplies Chinese officials who hold impressive titles to speak at events on the American campuses.

The beribboned accolades go surprisingly far in turning the heads of American college presidents, but that isn’t all there is to the Chinese soft-power strategy behind the Confucius Institutes. The Chinese government fully realizes the vulnerability of American colleges and universities that lies in their financial dependence on tuition. China can turn on the tap to full-tuition paying Chinese students, turn it down, or shut it off. A college or university that becomes dependent on this flow of international students is loath to offend the Chinese government. China is now by far the largest source of international students in the U.S., comprising 31 percent of the total. In 2015, there were some 328,000 Chinese students studying in American universities.

Vulnerability to China’s control of the flow of students to the U.S. is one thing. The opportunity for American colleges and universities to their own open programs in China is another. This prospect is regularly dangled in front of American college and university presidents, and with it comes both a potentially large new income stream and international prestige.

Forfeiting a bit of academic integrity to attain such rewards must seem to many college presidents a small price to pay. Or if not “many” college presidents, at least the hundred or so who have said yes to the offer to have a Confucius Institute on campus.

There is much more to this story, but I will leave it for Rachelle to tell. She is the intrepid researcher who has ventured forth on a series of NAS projects that have taken her into counsels of groups that are not naturally friendly to the National Association of Scholars. Rachelle was the lead researcher and first author of Sustainability: Higher Education’s New Fundamentalism (2015); researcher and author of Inside Divestment: The Illiberal Movement to Turn a Generation Against Fossil Fuels (2015); and our observer at a Black Lives Matter training seminar. Studying Confucius Institutes proved even harder than these previous assignments. It became clear that the Chinese government did not at all welcome our attention.

A last few words of prefatory caution. We limit ourselves in the body of this report to what we know for sure. There are no smoking guns. There is instead a scrupulously clean room and a cast of very polite people who have hardly anything to say beyond banalities. Rachelle describes this eerie scene in exact detail and without shading. The reader is free to take all this at face value, in which case the report will supply only a minimalist description of décor. All nations, after all, attempt to put their best foot forward with both friends and rivals. There is no harm in that, and it is possible that Confucius Institutes are best seen as the equivalent of the Alliance Française, the Goethe-Institut, the British Council, the Instituto Cervantes, or the Società Dante Alighieri. You must be the judge of that.

Introduction

Since 2005, more than 100 Confucius Institutes have opened at American colleges and universities. One hundred three remain in operation. These centers, many offering courses in Chinese language and culture, are funded by an agency of the Chinese government’s Ministry of Education—the Office of Chinese Languages Council International, better known as the Hanban. The Hanban also operates similarly organized Confucius Classrooms at 501 primary and secondary schools in the United States. These 604 educational outposts comprise a plurality (38 percent) of China’s 1,579 Confucius Institutes and Classrooms worldwide.

China’s investment in these overseas centers is increasing. In the last year, the number of Confucius Institutes and Confucius Classrooms in the world rose by almost 40 percent, from just over 1,110. In the US, the number of Confucius Institutes (CIs) and Confucius Classrooms (CCs) increased by nearly 35 percent. The growing number of US Institutes and Classrooms led the Hanban to open a branch office in Washington, D.C. The Confucius Institute U.S. Center, which organizes and supports the CIs and CCs in the United States, was chartered in 2013 but only in recent months hired senior staff and recruited board members.2

In the last decade, many observers have questioned the innocence of China’s interest in operating Confucius Institutes. The Hanban, part of the Chinese Ministry of Education, has shrouded Confucius Institutes in secrecy. At most Institutes, the terms of agreement are hidden. China’s leaders have not assuaged worries that the Institutes may teach political lessons that favor China. In 2009, Li Changchun, then the head of propaganda for the Chinese Communist Party and a member of the party’s Politburo Standing Committee, called Confucius Institutes “an important part of China’s overseas propaganda set-up.”3

The Hanban wields hefty influence in its Institutes. Confucius Institute instructors are screened, trained, and “dispatched” from China by the Hanban, which also pays their salaries and often provides housing.4 The Hanban supplies textbooks, along with annual grants around $100,000 to cover operating expenses and subsidize university staff salaries. The Confucius Institute Constitution on the Hanban’s website implies that Chinese law applies within the premises of its Institutes. Many Institutes are reluctant to criticize the Chinese government or discuss subjects censored in China, such as the Tiananmen Square massacre. Host universities have on occasion felt compelled to comply with Chinese political preferences. In 2009, North Carolina State University (NCSU) rescinded an invitation to the Dalai Lama to speak on campus. NCSU has a Confucius Institute, and local observation state that pressure from the Confucius Institue was responsible for NCSU’s about-face.

A number of professors have protested the establishment of Confucius Institutes at their universities, charging that the Institutes usurp faculty control and leave the university beholden to a foreign funder. The University of Chicago closed its Institute in 2014 after 100 professors signed a petition noting the “dubious practice of allowing an external institution to staff academic courses within the University.”5 Shortly afterward, Pennsylvania State University announced that it, too, would sever its relationship with the Hanban. Other universities have retained their Institutes to the chagrin of some professors. Professors around the country report that their university’s Institute, usually established without their knowledge, competes with their modern language department’s regular course offerings in Chinese and operates beyond the purview of the faculty.

Such concerns have led the American Association of University Professors to denounce Confucius Institutes as an arrangement that “sacrificed the integrity of the university.”6 New Jersey Congressman Chris Smith has held two Congressional hearings on the Institutes and asked the Government Accountability Office to investigate.7 University of Chicago anthropologist Marshall Sahlins has documented a series of troubling occurrences at Confucius Institutes worldwide in his book Confucius Institutes: Academic Malware.8 A number of scholars of China have published and testified regarding their concerns, including Perry Link,9 Lionel Jensen,10 and Steven Levine.11

Defenders of Confucius Institutes parry that China’s outreach is friendly, or at least no worse than that of the United Kingdom, France, or Germany, all of which operate educational centers in foreign countries not least as exercises in building “soft power”—a country’s promotion of its culture and its economy as a way to extend its political influence. South Korea and Japan, such defenders aver, also provide funding for courses in their nation’s language and culture. Several administrators or professors connected to Confucius Institutes told us they thought Saudi Arabia’s increasing investment in American higher education has not attracted the same criticism that Confucius Institutes do, perhaps because of a bias against China.

Some directors of Confucius Institutes report that they have never felt pressure to whitewash Chinese history and have been free to use textbooks of their choice instead of the Hanban’s. Some say the hype over Confucius Institutes stems from a few high-profile, poorly understood scandals, and that China’s claim to ownership of Confucius Institutes is only paper-deep. The real authority, they argue, rests with the host university, which accepts the Hanban’s money to support its own initiatives.

Much remains murky about Confucius Institutes. Defenders and opponents have each seized on examples favorable to their case. To evaluate the place of Confucius Institutes in American higher education, the National Association of Scholars examined 12 Confucius Institutes, two in New Jersey and ten in New York. We asked about hiring policies, formal protections for academic freedom, textbooks, course offerings, funding policies, and formal and informal speech codes. Some Confucius Institutes were more open than others, and the depth of the information we were able to procure varies from one Institute to another. But put together, our case studies offer insight into the inner workings of Confucius Institutes at American institutions. Our findings also illustrate the way that Confucius Institutes exert pressure on faculty members and administrators at their host institutions.

We found that certain practices can vary from Institute to Institute. Some Confucius Institutes grant more authority to the host university and to the local faculty than do others. Institutes faced varied levels of scrutiny from the Hanban. Some reported an outright ban on discussing subjects that are censored in China; others reported freedom of speech. But overall we found that to a large extent, universities have made improper concessions that jeopardize academic freedom and institutional autonomy. Sometimes these concessions are official and in writing; more often they operate as implicit policies.

We found cause for concern in four areas.

- Intellectual freedom. Official Hanban policy requires Confucius Institutes to adhere to Chinese law, including speech codes. Chinese teachers hired, paid by, and accountable to the Chinese government face pressures to avoid sensitive topics, and American professors report pressure to self-censor.

Although some teachers and professors within Confucius Institutes claimed complete freedom to express themselves, others did not. Several Chinese directors of Confucius Institutes described taboos on topics that are censored in China, such as the Tiananmen Square massacre.

Formal protection for the academic freedom of Chinese teachers in Confucius Institutes is virtually nonexistent. Almost no teachers within Confucius Institutes are hired as employees of the host university with standard protections for academic freedom. Most are hired by, paid by, and report to the Hanban, which reserves the right to remove teachers who violate Chinese law—including speech codes. There is some evidence that the Hanban may provide teachers with stock answers to questions it wishes to avoid. When we asked Chinese teachers and directors what they would say to a student who asked about Tiananmen Square, several replied that they would talk about the Square’s historic architecture.

There is some evidence that the Hanban may provide teachers with stock answers to questions it wishes to avoid. When we asked Chinese teachers and directors what they would say to a student who asked about Tiananmen Square, several replied that they would talk about the Square’s historic architecture.

We also found that some professors within the university felt pressured to self-censor. Those affiliated with the Confucius Institute sensed the need to maintain a friendly relationship with the Hanban. Those outside the Confucius Institute felt pressure from the university—most immediately from their department—to protect the Confucius Institute’s reputation. In most cases the censorship was relatively mild, but ideological censorship of any kind is out of place in higher education. Some reported the temporary removal of Taiwanese flags or literature when Hanban officials visited. Others described extended debates over language calculated to sidestep political quagmires in China.

- Transparency. Contracts between American universities and the Hanban, funding arrangements, and hiring policies for Confucius Institute staff should be publicly available. Some universities went to extraordinary efforts to avoid scrutiny, cancelling meetings and forbidding NAS from visiting campus.

None of the 12 Confucius Institutes we examined discloses publicly its contract with the Hanban, its budget, or its funding arrangements. Many contracts include nondisclosure agreements, in which the Hanban asks the university to “treat this Agreement as confidential,” and not to share it without the Hanban’s express written consent. The director of one Confucius Institute, at Pace University, agreed to share an unsigned draft version. None of the 12 universities agreed to release signed final copies of its contracts until NAS filed requests under the Freedom of Information Law in New York and New Jersey. Through these requests, we obtained contracts from the eight public universities among our case studies.

NAS also met significant resistance to any questions about the Confucius Institutes. At only two of the 12 institutes did the director agree to speak to us. Two directors, at the University at Albany and Binghamton University, agreed to a meeting but cancelled at the last minute. At Binghamton University, director Zu-yan Chen also cancelled our meetings with members of the Confucius Institute staff. The Alfred University provost, upon learning that Rachelle Peterson had secured permission from a Confucius Institute teacher to visit her course, interrupted the class to eject Rachelle and forbid her from returning to campus.

We did find some university administrators open to conversation. At the University at Buffalo, vice president for international education Stephen Dunnett spent an hour and a half with Rachelle Peterson, but did not respond to follow-up queries or provide further information he promised during the meeting. Rutgers University chancellor Richard Edwards also agreed to a meeting, and called back a week later to give more detailed information. But in most cases, universities merely gesture at transparency.

- Entanglement. Confucius Institutes are central nodes in a complex system of relationships with China. Confucius Institutes attract full-tuition-paying Chinese students, fund scholarships for American students to study abroad, and offer other resources. Universities with financial incentives to please China find it more difficult to criticize Chinese policies.

Confucius Institutes are part of a growing web of connections between American universities and China. Other strands of this web include American satellite campuses in China, such as New York University’s Shanghai campus; an increase in semester-long student and faculty exchanges; and the skyrocketing number of Chinese students enrolling in American universities. According to the Institute of International Education, 328,547 Chinese students enrolled at American universities during the 2015-2016 school year—31.5 percent of all foreign students in the US.12 Those numbers are up from 62,582 Chinese students in 2005-2006.

NAS supports the exchange of ideas across countries and we welcome opportunities for American and Chinese students to visit and study in other countries. There is some cause for concern, though, that American universities have already become financially dependent on their ties to China. Foreign students, in particular, pay out-of-state tuition and become lucrative prospects for universities to recruit.13

As numerous professors and administrators at universities with Confucius Institutes reminded us, the Hanban’s funding of Confucius Institutes comes at a time of university budget cuts, making the influx of Chinese cash especially alluring. The Hanban generally requires host universities to contribute 50 percent of the Institutes’ operating budgets, but most universities fulfill a substantial portion of this requirement with in-kind contributions of classroom space and office equipment.

Confucius Institutes also play a major role in cementing relationships between American universities and China. Universities that pass the Hanban’s vetting procedures for Confucius Institutes are fast-tracked for approval in student exchanges. They also earn greater name recognition among Chinese students looking to earn a degree from an American institution. Several of the Confucius Institute contracts we examined included plans for student and faculty exchanges, scholarships for American students to study in China, and other incentives.

We do not condemn the introduction of new programs that increase students’ opportunities to study abroad. But we do note that Confucius Institutes have grown into a central node of US-Chinese academic exchanges, making it increasingly difficult for universities to withdraw from Confucius Institutes without jeopardizing other financial relationships.

- Soft Power. Confucius Institutes tend to present China in a positive light and to focus on anodyne aspects of Chinese culture. They avoid Chinese political history and human rights abuses, present Taiwan and Tibet as undisputed territories of China, and develop a generation of American students with selective knowledge of a major country.

Political scientist Joseph Nye coined the term “soft power” to denote a country’s ability to exercise authority by attraction, rather than by coercion. Soft power rests on the ability to shape the interests and desires of the other party to match or become compatible with one’s own.

Confucius Institutes are a textbook example of a soft power initiative. Students who attend Confucius Institutes will develop a natural interest in building professional relationships with those in China. Universities that receive Chinese largesse will find it in their interest to maintain a friendly relationship with China, and may find cause to stay silent in certain controversies such as China’s treatment of dissident professors. We support efforts to enable students and professors to learn more about China—and to share Western values of free expression—but we also note that the arrangement of Confucius Institutes grants significant authority to a party outside the university.

The positioning of Confucius Institutes on college campuses, meanwhile, is a boon to China. Securing a relationship with major American universities, including Stanford and Columbia, boosts China’s image on the world stage. It is naive to think that China’s multimillion-dollar investment in American education stems from pure generosity. We report the findings of our 12 case studies below, along with examples drawn from other Confucius Institutes. We first cover the general structure and history of Confucius Institutes, then specific topics related to intellectual freedom and the autonomy of the university, and finally offer short written accounts of the most prominent Confucius Institutes in our case studies.

The Hanban

“Hanban” is the executive body of the Office of Chinese Languages Council International, an agency under the Chinese Ministry of Education responsible for sending Chinese teachers and resources to other countries. The Hanban was founded in 198714 and opened the first Confucius Institute (in South Korea) in 2004. Confucius Institutes are one project within the Hanban, but as Confucius Institutes have grown to become the Hanban’s most visible project, the Hanban has sometimes referred to itself as Confucius Institute Headquarters. The head and key staff of the Hanban are also the highest ranking authorities of the Confucius Institute Headquarters.

The Hanban is closely tied to the Chinese Ministry of Education, though it obfuscates its relationship to the Chinese government. According to the Hanban’s website, “Hanban/Confucius Institute Headquarters” is “affiliated with” the Chinese Ministry of Education.15 By the Confucius Institute Constitution, the Hanban is “a non-profit organization that has the independent status of a corporate body.”16 The Chinese Ministry of Education lists the Hanban on its website as one of 34 “Affiliated Organizations” along with organizations such as the China National Institute for Educational Research, China Education Television, and China Vocational and Technical Education Society.17

But the Hanban is more closely linked to the Chinese regime than these statements indicate. Hanban’s operations are intertwined with those of the Ministry of Education. For instance, the Hanban’s published criteria for Chinese teachers include the requirement that prospective teachers “satisfy the requirements on selection by the Ministry of Chine (sic) Education.”18 The director general of the Hanban, Xu Lin, is a career government bureaucrat who worked her way up through the Chinese Ministry of Education. When we interviewed Chinese directors of Confucius Institutes, many used the terms “Hanban” and “Chinese Ministry of Education” as near synonyms.

The Hanban’s leadership is saturated with Communist Party leaders and career bureaucrats. Its governing body, the Chinese Language Council International, includes representatives from 12 Chinese state agencies. Most notable among these are the State Press and Publications Administration (which handles state-run media and propaganda), the General Office of the State Council, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Education. The other eight agencies are the Ministry of Finance, the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council, the State Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Culture, the State Administration of Radio Film and Television (China Radio International), the State Council Information Office, and the State Language Work Committee.19 The Council itself is technically a nonprofit nongovernmental organization, but in practice it is composed exclusively of high-ranking members of the Chinese Communist Party and Chinese government.

The Chinese Language Council International is the ultimate authority over the Hanban, though the Hanban has its own executive staff. The Director General of the Hanban is also chief executive of the Confucius Institute Headquarters and the legal representative of the Hanban.20 Xu Lin, who fills these roles, is simultaneously a Counselor in the State Council, the 35-member top-ranking administrative arm of the People’s Republic of China. Xu has held this position since 2009.

Of the four deputy directors general of the Hanban/deputy chief executives of the Confucius Institute Headquarters, three previously built their careers in the Chinese Ministry of Education. (See Appendix II.)

Some Confucius Institute directors have also been rewarded with government jobs at the end of their terms. In November 2015, the former director of the Confucius Institute at Georgia State University (previously the director of the Confucius Institute at Arizona State University) was recommended as the sole candidate for deputy president of the Hong Kong Institute of Education.21

Why Confucius?

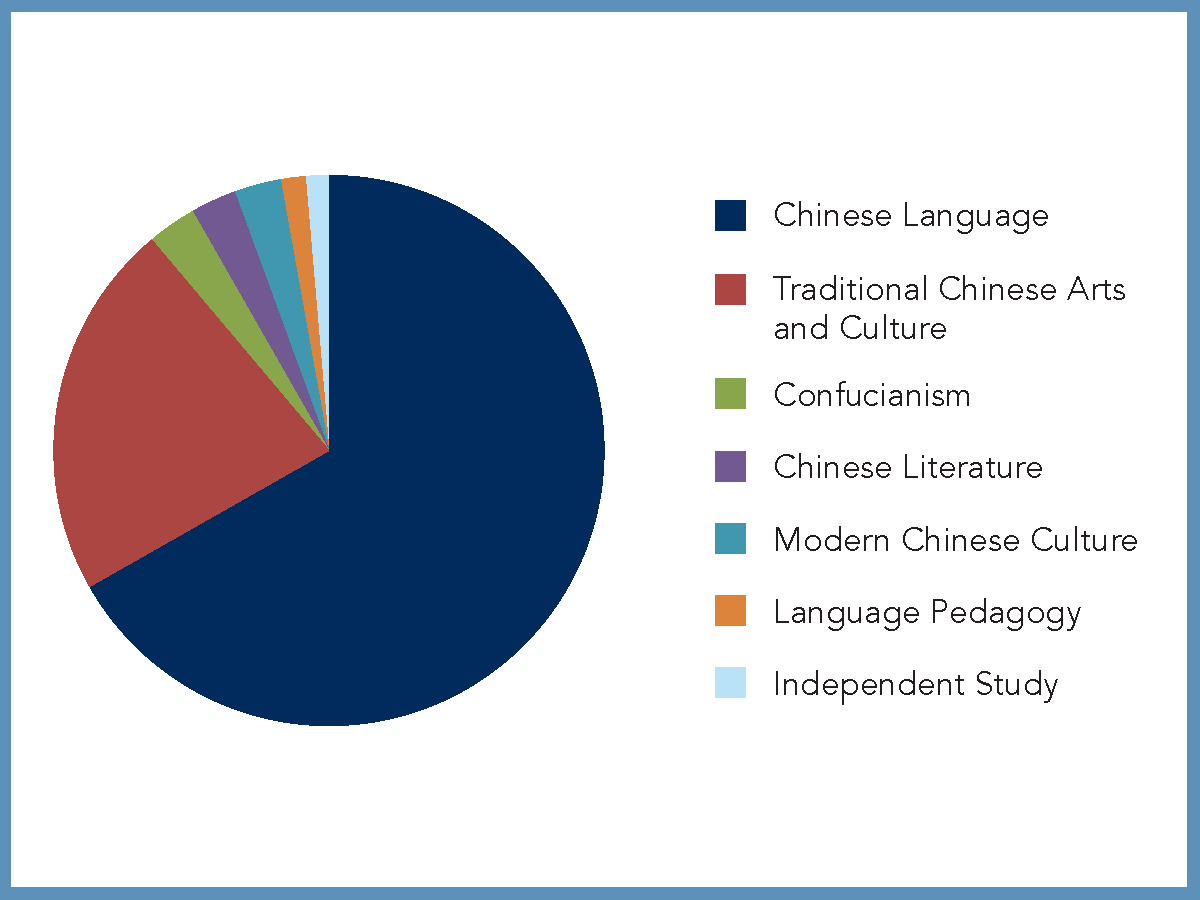

Confucius Institutes primarily teach courses on Chinese language, and offer a variety of traditional arts and culture events such as paper cutting, tea ceremonies, and Chinese New Year celebrations. Few teach about Confucius, so why name the Institutes after him?

Confucius, the fifth century BC Chinese philosopher whose Analects deeply shaped Chinese society, is familiar to many in the West, who see him as among the most accessible, anodyne aspects of Chinese culture. Confucianism has transcended the East to become well-known to the West, making the philosopher’s name a prime tool for cultural diplomacy. “‘Mao Institutes’ would somehow have lacked appeal,” the Economist noted in 2015, reflecting on China’s resurging interest in the philosopher.22

The rise of Confucius Institutes has coincided with a resurgence of interest in Confucianism in China. Mao Zedong rooted out Confucianism, razing temples and destroying the sage’s grave, in order to weed out ancient “feudal” ideas. But in recent years, Chinese President Xi Jinping has encouraged schools to teach children about Confucius and hired once-marginalized scholars to lead seminars for government officials and bureaucrats.23 China is finding that Mao’s demolition of ancient Chinese culture and break-neck social and economic transformation left many uprooted and disconnected from Chinese history. Mr. Xi sees an opportunity to rebuild China’s pride in its history while remaking Confucius’s image to conform to socialist dogmas. In particular, Confucius’s emphasis on “order, hierarchy, and duty to ruler and family” offer openings for appropriation by Mr. Xi’s regime.24

The Economist has noted that Mr. Xi oversaw a 2014 meeting of the Politburo, the Chinese Communist Party’s ruling committee, in which he emphasized the need to used traditional culture as the “wellspring” of the party’s values. That year, he also attended Confucius’s 2,565th birthday party, and in 2015 state media announced that the “hottest topic” in humanities research the previous year was in finding ties between Marxism and Confucianism.25

The Chinese government has invested heavily in molding Confucius’s image and projecting it to an international audience. Projects include a $3.8 million renovation of the Confucius Temple, Mansion and Cemetery in 2010, advertising Confucius’s hometown Qufu in Times Square, and building a railway station for the tiny town along the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway.26

A 2015 survey of Chinese citizens’ political opinions found that interest in Confucianism corresponded with “leftist” opinions supportive of the Communist party’s “authoritarian rule, including supremacy of the state and nationalism.” The authors, Jennifer Pan and Yiqing Xu, found that those with “support for Chinese traditions, for example advocated by Neo-Confucians,” tended to see “Western liberal political and social values” as “hostile.”27

Confucius Institutes Worldwide

The Hanban claims to sponsor 512 Confucius Institutes and 1,074 Confucius Classrooms in 131 nations, for a total of 1,586 educational outposts. We have verified the existence of 103 of the 110 Confucius Institutes the Hanban lists as existing at American colleges and universities. (We remove six Classrooms that appear on the Institutes lists and one Institute, at Dickinson State University, that the university cancelled before it opened.28)

The Hanban’s projects are clustered in English-speaking nations, particularly in the United States. The United States has more CIs and more CCs than any other nation. Its 103 CIs comprise 20 percent of all such institutes, and its 501 CCs make up 47 percent of all Confucius Classrooms worldwide. In all, 38 percent of the Hanban’s sponsored Confucius Institutes and Classrooms are located in the United States.

The United States possesses far more Confucius Institutes and Classrooms than any other nation. The United Kingdom, its closest competitor, has 29 CIs and 148 CCs, or about 11 percent of the Hanban’s outposts. Australia comes third, with 14 CIs and 67 CCs, or 5 percent of the worldwide total.

The Hanban also has high numbers of outposts in Italy (12 CIs, 39 CCs), South Korea (23 CIs, 13 CCs), Thailand (15 CIs, 20 CCs), Germany (19 CIs, 4 CCs), Russia (17 CIs, 5 CCs), Japan (14 CIs, 8 CCs), and France (17 CIs, 3 CCs). In keeping with its increased infrastructure investment in Africa, China has also placed Confucius Institutes or Classrooms in 38 of the 54 nations in Africa.

Each Confucius Institute partners with a Chinese university. The 103 CIs in the US are partnered with 80 different universities in China. One CI, at Pace University in New York, is paired with both a university and a publishing group. Fourteen Chinese universities are partners in more than one American-based Confucius Institute. (See Appendix I.)

Our Case Studies

We concentrate on Confucius Institutes at colleges and universities in the United States. We interviewed CI directors and teachers from Confucius Institutes across the US but focused our examination on the 12 Confucius Institutes located in New Jersey (2) and New York (10). Eleven of these 12 are housed at universities, and one is at a private organization, China Institute.

Of the 11 colleges and universities, nine are public and two (Columbia University and Pace University) are private. Both New Jersey universities are public. Of the seven public New York universities, all are part of the State University of New York (SUNY) system.

Of the 12 CIs we discuss in our case studies, the oldest one opened at China Institute in September 2005, and the second-oldest at Rutgers University in May 2008. The newest CI, at New Jersey City University, opened in June 2015.

Most of the 12 focus on teaching the Chinese language. One, the Confucius Institute of Chinese Opera at Binghamton University, partners with China’s National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts to perform Chinese opera and instruct students in traditional Chinese music. The Confucius Institute for Business at the SUNY Global Center caters to professionals preparing for business trips to China. The Confucius Institute at SUNY College of Optometry works with Wenzhou Medical University to teach students about the Chinese healthcare system and traditional Chinese medicine.

| American Institution | Chinese Institution | Confucius Institute | Confucius Institute Location | Date Started |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Jersy City University | Jilin Huaqiao Foreign Languages Institute | Confucius Institute at New Jersy City University | Jersey City, NJ | 6/1/2015 |

| Rutgers University | Jilin university | Confucius Institute of Rutgers University | New Brunswick, NJ | 5/1/2008 |

| Alfred University | China University of Geosciences, Wuhan | Confucius Insittute at Alfred University | Alfred, NY | 1/20/2009 |

| Binghamton University | National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts | Confucius Institute of Chinese Opera at Binghampton University | Binghampton, NY | 11/6/2009 |

| China Institute | East China Normal University | Confucius Institute at China Institute | New York, NY | 9/1/2005 |

| Columbia University | Renmin University of China | Confucius Institute of Chinese Language Pedagogy | New York, NY | 9/1/2005 |

| Pace University | Nanjing Normal University and Phoenix Publishing and Media Group | Confucius Institute at Pace University | New York, NY | 5/19/2009 |

| Stony Brook University | Zhongnan University of Economics and Law | Confucius Institute at Sony Brook University | Long Island, NY | 5/19/2010 |

| SUNY Global Center | Nanjing University of Finance and Economics | Confucius Institute for Business at SUNY | New York, NY | 12/10/2010 |

| SUNY College of Optometry | Wenzhou Medical University | Confucius Institute at SUNY College of Optometry | New York, NY | 10/27/2010 |

| University at Albany | Southwestern University of Finance and Economics | Confucius Institute for China's Culture and the Economy | Albany, NY | 9/23/2013 |

| University at Buffalo | Capital Normal University | UB Confucius Institute | Buffalo, NY | 4/9/2010 |

Organization

Each Confucius Institute is a joint venture between the host university, a partner Chinese university, and the Hanban. The two universities sign a Memorandum of Understanding that serves as their contract for establishing the Institute.

The host university provides a venue, a director (what the Hanban calls the “foreign director”), some portion of the funding (which includes in-kind contributions such as office space and supplies), and sometimes administrative staff. The Chinese institution grants leaves of absences to some of its professors, who serve as Chinese teachers and as the “Chinese director.” Thus there are two directors: the “foreign” or local (in our case studies, American) director, and the Chinese director.

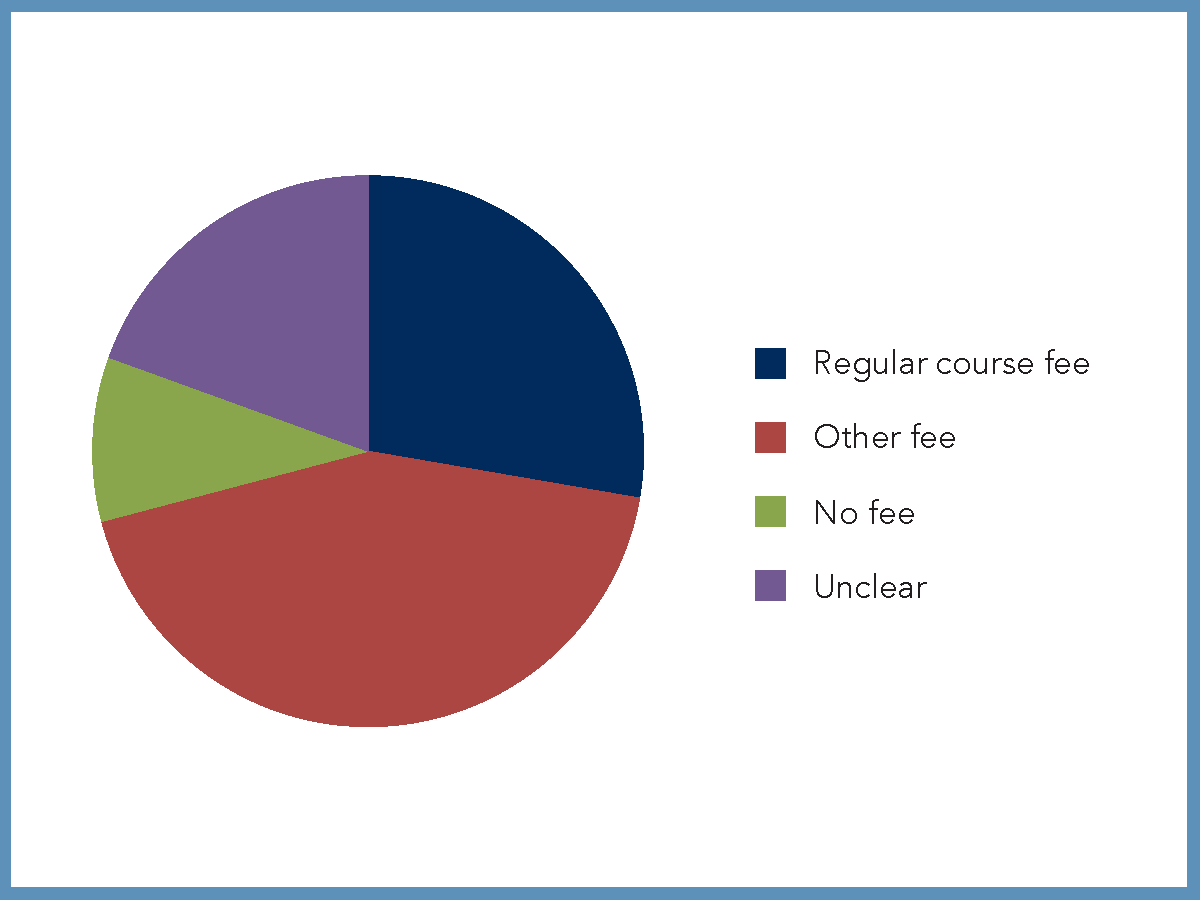

The Hanban supplies textbooks and funds to cover operating expenses and to pay the teachers and Chinese director. Under some arrangements, the Hanban also pays a portion of the foreign director’s salary. Where we were able to obtain information on finances, we found that the Hanban’s start-up grant tends to be around $150,000, with $100,000 for subsequent years.

Most Confucius Institutes are stand-alone enterprises within the university. The Hanban, in its template contract for establishing a CI, proposes that each CI be set up as its own “non-profit educational institution.”29 Few CIs are integrated into academic departments, though some offer their own credit-bearing courses or supply the teachers for credit-bearing courses within other academic departments. More often CIs offer separate, non-credit language instruction, and seminars in Tai Chi or arts such as Chinese paper cutting and painting. Many hold public celebrations of the Chinese New Year.

Each CI is under the jurisdiction of the host university, but to varying degrees. Some measure of authority is shared with the Hanban, which retains the right to dismiss the teachers and Chinese director and to veto CI programs.30

Each year the co-directors of the CI must propose projects and courses to the Hanban, which under the CI Constitution is tasked with “examining and approving the implementation plans of annual projects, annual budgetary items, and final financial accounts of individual Confucius Institutes.” The Hanban is also responsible for “providing guidelines and making assessments to activities carried out by Confucius Institutes” and “supervising their operations” in order to promote “quality assurance.”31 The Hanban also “reserves the right to terminate the Agreements” with Confucius Institutes that “violate the principles or objectives” of the Hanban or “fail to reach the teaching quality standards” of the Hanban.32

In none of the CIs we examined did the host university’s Faculty Senate have authority or an advisory role regarding the establishment of the Confucius Institute or the development of its course offerings. (One, the University at Buffalo, does give relevant academic departments a say in which Chinese teacher to hire from among the Hanban’s nominees, and asks each department to then assess the teacher’s work.)33

A common complaint from professors of Chinese language is that the Confucius Institute classes purporting to teach the Chinese language are established without their knowledge, consent, or professional input. David Prager Branner, who was an associate professor of Chinese at the University of Maryland in 2005 when it became the first American university to open a Confucius Institute, noted that the director of the CI was a physicist who was born in China but had no professional expertise in teaching Chinese. “Even my dean didn’t know of the CI until it was announced by the president,” said Branner, noting that the School of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures was kept in the dark about the arrangement until it was finalized.34

Of the 12 CIs in our case studies, three have a clear institutional department to which to report. At Rutgers University, “the Institute reports directly to the Office of the Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and is overseen by the CIRU Board of Directors.”35 At Alfred University, the CI “is affiliated directly under the Provost’s Office at Alfred University.”36 At the University at Buffalo, “the Confucius Institute is housed within the College of Arts and Sciences” and “collaborates closely” with “many other departments, programs, schools, and student organizations, including: Office of the Vice Provost for International Education, Graduate School of Education, Chinese Language Program in the Department of Linguistics, Asian Studies Program, Chinese Student and Scholar Association.”37 The Buffalo CI is more closely integrated into the rest of the university than any other CI we examined.

All other CIs report primarily to their boards of directors. Most universities retain their authority over the CI’s day-to-day operations through indirect means, such as having the president or provost sit on for instance, at New Jersey City University, the director of the CI, Daniel Julius, is also senior vice president and provost.38 At Binghamton University, the chairman of the CI board is Donald Nieman, Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost.39

The Board

Each CI has a board of directors that oversees its work. The board approves the Institute’s annual plans, reports for the Hanban, and its budget. The board also has a role in appointing and dismissing the foreign and Chinese directors. The Confucius Institute Constitution holds that the board is “responsible for appointing and dismissing Directors and Deputy Directors of the Confucius Institute” and that “The appointments of Directors and Deputy Directors for joint venture Confucius Institutes shall be decided upon negotiations between the Chinese and overseas partners.”40 (We discuss hiring in greater detail in subsequent sections.) CI board, or appointing a senior member of the administration as the CI director.

The Confucius Institute Constitution does not advise the number or balance of board members but defers these questions to “consultation,” presumably between the two partner universities.41 Of the nine CIs we were able to obtain information for, the average number of board members was eight. At eight of the nine institutions, the chairman was a senior administrator of the American institution and the vice-chairman was a senior administrator of the Chinese institution. Only at the SUNY Global Center was the board chairman a representative of the Chinese university (Song Xuefeng, president of Nanjing University of Finance and Economics), while the deputy chairman represented the SUNY Global Center. Pace University, according to a draft contract with Nanjing Normal University, rotates the chair every two years between a representative of Pace and a representative of Nanjing Normal University.42

The largest board size was 15 members; the smallest had six members.

At six of the nine CIs, a majority of the board members were affiliated with the American host institution, usually by one seat. The greatest difference was at Stony Brook University, where six of the seven board members held positions at Stony Brook, and only the Chinese director, Dr. Shijiao Fang from Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, represented the Chinese partner institution.43

One Confucius Institute board had a majority of members from the Chinese partner institution. At the SUNY College of Optometry, four of the seven board members were affiliated with Wenzhou Medical University.44

At two, the University at Buffalo and SUNY Global Center, the eight-member board was evenly divided between representatives of the two partner universities.

With the exception of the University at Buffalo, all board members were affiliated with one of the two partner universities. At Buffalo, one board member was president of a local business, Rich Products. Three other board members were from the University at Buffalo and four from Capital Normal University in China.

| University | Board Members from American University | Board Members from Chinese University | Board Members from Private Companies | Total Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Jersey City University | 6 | 5 | 0 | 11 |

| Rutgers University | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| Alfred University | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Binghamton University | 8 | 7 | 0 | 15 |

| SUNY College of Optometry | 3 | 4 | 0 | 7 |

| Sony Brook University | 6 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| SUNY Global Center | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| University at Albany | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| University at Buffalo | 3 | 4 | 1* | 8 |

*Mr. William G. Gisel, Jr., chief executive officer and head of Rich Products' Executive Leadership Team, Buffalo, NY.45

Staff

The Hanban’s Confucius Institute Constitution delineates the general structure and division of authority between the two partners. According to the Constitution, the foreign (in our case studies, American) director assumes “the main responsibility for the Institute’s daily operation and administration.”46

The Chinese co-director’s responsibilities vary, but typically concentrate on writing reports for the Hanban and supervising Chinese teachers. At Pace University, the Chinese director Wenqin Wang, who previously taught English as a Foreign Language at Nanjing Normal University in China, told us she oversees the Chinese teachers, coaches them to navigate cultural differences, and handles paperwork for the Hanban.47

At the University at Buffalo, the Chinese associate director assists an American associate director “in the administration of the Institute,” prepares “Chinese language versions of plans, reports, and budgets,” and “as time allows and need arises, may provide instruction in Institute programs.”48 At the Confucius Institute for Business at the SUNY Global Center, the Chinese director is “responsible for communicating with: the [Confucius Institute] Headquarters, NUFE [Nanjing University of Finance and Economics], China’s Consulate in New York, and overseas Chinese communities.” The Chinese Director also performs a variety of administrative roles, and helps the American Director “recruit, select and train staff.”49

The teachers and co-directors from China sign short contracts with the Hanban, usually for two years. Some are professors at universities in China, and receive leaves of absence from their home universities for the duration of their stints at Confucius Institutes.50 They typically return to their previous positions in China, depending on their good service at the Confucius Institute. Some go on to another Confucius Institute, and others request and receive extensions for another year at the same CI. At Pace University, director Joseph Tse-Hei Lee planned to request a one-year extension for a teacher who had spent two years helping Pace develop an app to teach Chinese.

None of the Chinese directors or teachers we spoke to had signed contracts with the host university. Tamara Cunningham, assistant director of the CI at New Jersey City University, told us she and the other professors would prefer to hire the Chinese teachers as adjuncts, but could not under the agreement the university signed with the Hanban. Under that agreement, the teachers sign contracts with the Hanban, not the host university, and are paid by the Hanban, which declined to provide lump sums of funding for the university to use in paying the teachers itself.51

Under such arrangements, the Chinese teachers and Chinese directors answer simultaneously to the American director, the CI board, and the Hanban. The American director and Chinese director provide the most immediate oversight, though in most cases it is the Hanban that provides teachers’ salaries and evaluates their performance.

The American director answers to the CI’s board. At some institutions, he also reports to the department under which the CI is organized (see “Organization” above). In cases where his salary is paid in part by the Hanban, he may have some additional obligations to the Hanban.

Hiring, Wages, and Responsibilities

American Directors

The American Director is appointed by and retains his position at the pleasure of the CI board of directors. Because the boards of directors comprise members of both the host university and its Chinese partner, the director receives the approval of both parties, though typically the host university plays a larger role in selecting the American director.

Some universities set forth in their contracts clear guidelines for the hiring process. At the University at Buffalo, the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and the Vice Provost for International Education hire the Confucius Institute director, subject to the formal approval of the Confucius Institute Board of Directors.52 E.K. Tan, the director of the CI at Stony Brook University, told us he was invited to apply for his position by Stony Brook’s Dean of International Academic Programs and Services, who chaired a search committee put together by the CI board of advisors. The board held final responsibility to formally approve Tan as director.53 Most contracts establishing CIs state only that the board of directors has the authority to “appoint” or “approve” the director.

The Director’s responsibilities include oversight of all Confucius Institute activity, though generally formal communication with the Hanban goes through the Chinese director.

Some CIs spell out the qualifications for CI directors. Five of the nine institutions that released copies or draft copies of their contracts had contractual language stipulating that the director must be a professor at the host university. One of these, the University at Buffalo, further specified that the director should be a tenured professor.54 Many contracts included similar language that the director should be one “with administrative abilities, and has been devoted to the Sino-America cultural exchange and the establishment of the Confucius Institute.”55 At Rutgers University, chancellor Richard Edwards, who oversees the Confucius Institute, told us his criteria include fluency in Mandarin, experience in managing and developing new programs, and interpersonal skills. The director at Rutgers need not be a professor, but could be appointed to a staff position, Edwards said.56

In practice, the American director is almost always a faculty member or administrator of the host university. Of the 12 CIs we studied, nine directors had other appointments within the host institution. The director of the one non-university CI, at the China Institute, had no other appointed position within the China Institute. At the SUNY College of Optometry, the director position was empty during the time we conducted our research. And at the University at Buffalo, the CI director Jiyuan Yu passed away while we were conducting our research. His position has not yet been filled.

Of the nine directors with university appointments, seven were professors and two were full-time administrators.

Of the seven professors who direct CIs, five have extensive professional expertise in Chinese language and culture. Dr. Wilfred V. Huang at Alfred University, is a professor of management, and at the University at Albany, Youqin Huang is associate professor of geography and planning. (At the University at Buffalo, where the director’s position is currently unfilled, the previous director Jiyuan Yu was a professor of philosophy.)

| University | Institute | Name | CI Postition | University Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Jersey City University | Confucius Institute at NJCU | Daniel Julius | Director | Senior Vice President and Provost |

| Rutgers | Confucius Institute of Rutgers University | Ching-I Tu | Director | Professor of Chinese and East Asian Studies |

| Alfred University | Confucius Institute at Alfred University | Wilfred V. Huang | Director | George G. Raymond Chair Professor of Management |

| Binghamton University | Confucius Institute of Chinese Opera at Binghamton University | Wilfred V. Haung | Directo | Distinguished Professor of Chinese Language and Literature |

| China Institute | China Institute Confucius Institute | Zu-yuan Chen | Director | None |

| Columbia University | Confucius Institute of Chinese Language Pedagogy | Lening Liu | Director | Professor of East Asian Languages and Cultures |

| Pace University | Confucius Institute at Pace University | Joseph Tse-Hei Lee | Executive Director | Professor of History, Co-director of B.A. program in Global Asia Studies |

| Stony Brook University | Confucius Institute at Stony Brook University | E.K. Tan | Director | Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies |

| SUNY College of Opometry | Confucius Insittute at SUNY College of Optometry | The Director Postition was empty as of November 2016 | ||

| SUNY Global Center | Confucius Institute for Business at SUNY | Mayalice Mazzara | Director | Director, JFEW-SUNY International Relations and Global Affairs Scholars Program |

| University at Albany | Confucius Institute for China's Culture and the Economy | Youquin Huang | Executive Director | Associate Professor of Geography and Planning |

| University at Buffalo | UB Confucius Institute | Jiyuan Yu (passed away during our research; position now unfilled | Director | Professor of Philosophy |

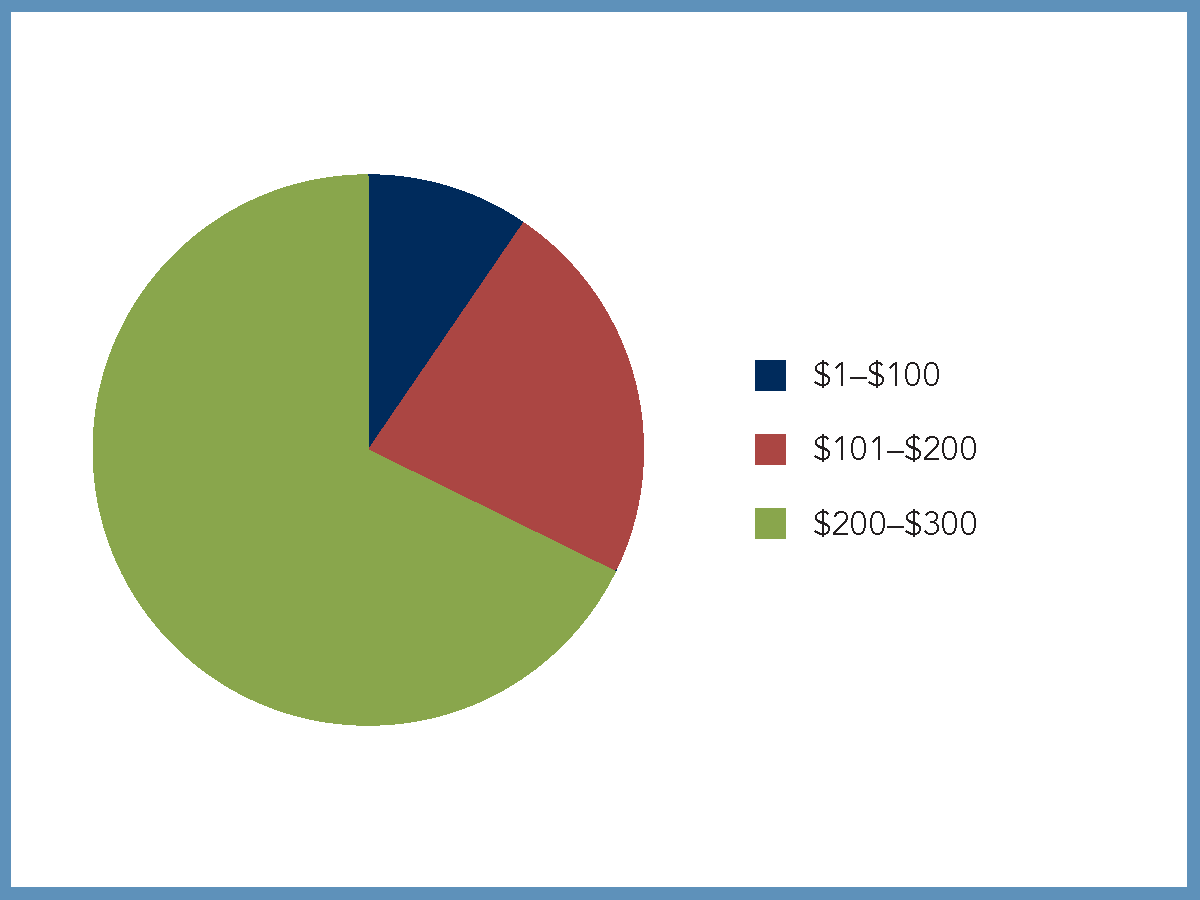

Many CI directors receive some compensation for their work. Of the six CIs that provided information to us, either in person or by copies of their contracts, three directors were paid exclusively by their host university, two were paid by the host university in part with subsidies from the Hanban, and one was not paid at all. At Stony Brook University, where university policies prevent any full-time professor from receiving competing external compensation, the CI director there is appointed to an unpaid service position.

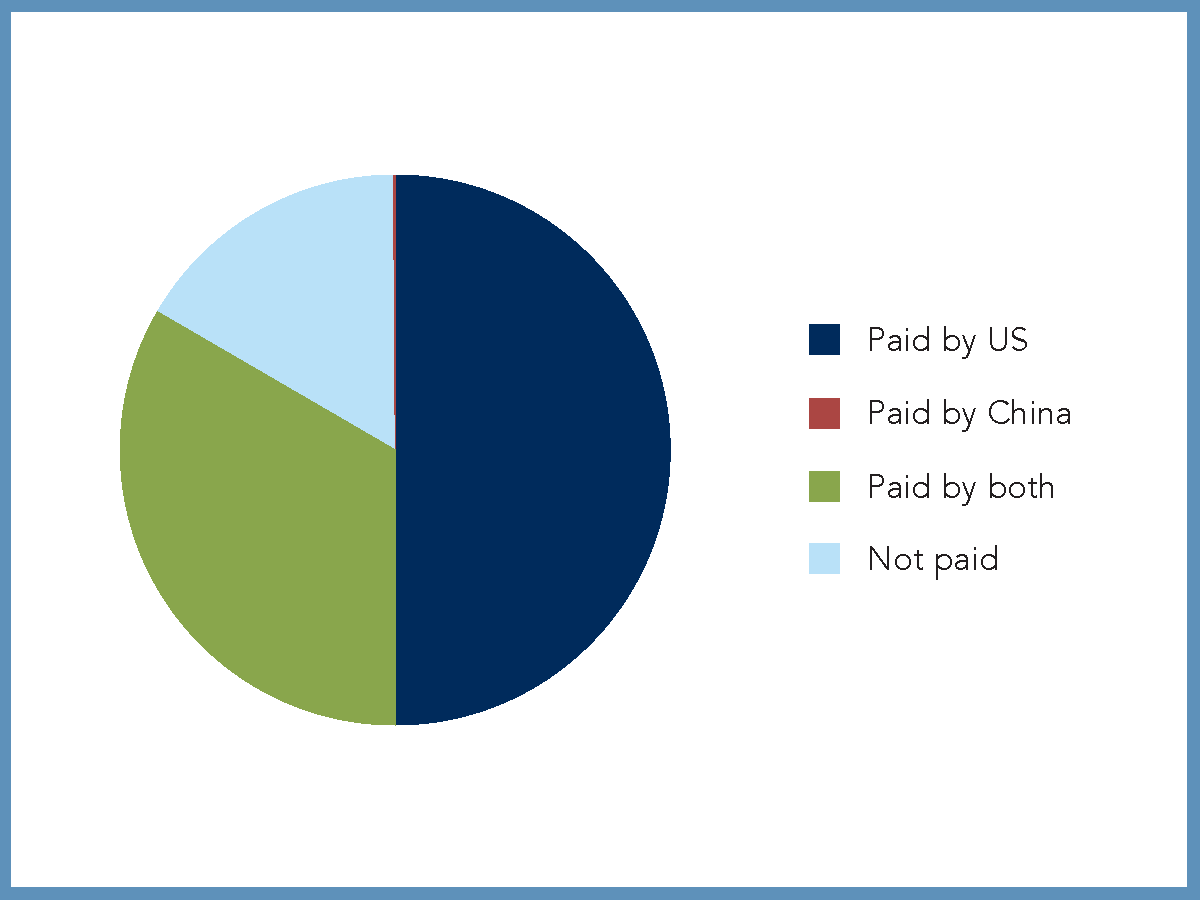

Figure 1 Who Pays Confucius Institute Directors

Chinese Directors

Chinese directors are nominated by a Chinese partner university or the Hanban to the host university, whose CI director usually plays a role in selecting which nominee to accept.

The Hanban puts forth the criteria for Chinese directors. They should be between 35 and 55 years old, healthy, familiar with the country to which they are appointed, proficient in the local language, comfortable using computer software and the internet, and “passionate about Chinese language teaching and Confucius Institute undertakings.” Prospective Chinese directors should hold the title of associate professor or higher, have at least one year’s administrative experience and some experience studying or working in another country, and should “be a qualified leader with cross-cultural communication skills and be efficient at executive tasks.” The requirements also hold that “the nominee must abide by laws and regulations in China and the destination country.”57

The Chinese directors and teachers we interviewed reported that the application process was not particularly competitive. “Not so much,” Pace CI Chinese director Wenqin Wang said when asked if the application process was difficult. “Language is most important requirement,” she said, noting the small pool of professors with sufficient English proficiency.58 Wang said she attended the Hanban’s annual training camp in China for new Chinese directors, along with about 160 other new directors.

Shijiao Fang, at the Stony Brook University Confucius Institute, said her home university in China announced that the Stony Brook CI needed a new Chinese director and invited professors to apply. She submitted her CV to a Zhongnan University panel, which selected which professors could then apply to the Hanban for the position. She estimated ten professors applied for the Chinese director position, compared to an average of 20 to 30 for professorships at universities in China. “For this position, the competition is not very strong, because they have to come to a foreign institution” and speak English well, Fang said. But because the applicants are professors who rose to the top of a “very competitive” process to secure an academic job in China, she felt it was overall a competitive process to earn a spot teaching in a foreign country.59

Most Chinese directors’ roles center on communicating with partners in China, coaching teachers, and handling paperwork for the Hanban. Wang, at Pace University, said her “primary task is to coordinate teachers and coordinate with the Modern Language Department,” which has Confucius Institute teachers run labs for the university’s regular Chinese 101 and 102 classes. Wang also handles “lots of coordinations, and communication with Pace and other organizations” in New York City that recommend students to the Confucius Institute.

At the SUNY Global Center, the Chinese director is “responsible for communication with the Headquarters, NUFE [Nanjing University of Finance and Economics], China’s consulate in New York, and overseas Chinese communities.”60 Likewise the University at Albany Chinese director is to “be the main liaison between the Confucius Institute, SWUFE [Southwestern University of Finance and Economics], and the Hanban.”61

Some Chinese directors also handle applications to the Hanban for funds. At the SUNY Global Center, the agreement between SUNY and Nanjing University of Finance and Economics specifies that the Chinese director is “responsible for applying to Headquarters for financing such events as cultural exchanges, marketing and advertising promotion of the Institute.”62 At the University at Buffalo, the Chinese Associate Director and the SUNY Associate Director are jointly tasked with monitoring the “use of funds allocated by the Headquarters to make sure the funds are used in conformity with regulations of the Headquarters and of the Research Foundation of SUNY.”63

To whom does a Chinese director report? The authority structure is muddled. Most Chinese directors serve as co-directors with the American director, though the American director generally takes precedence. Only at the University at Buffalo was the Chinese director officially subordinate to the American director.64

Chinese directors must balance the authority of the American host institution and the American director against the authority of the Hanban and their own home institution in China. Of the nine institutions for which we obtained contracts or draft contracts, four stipulated that “the institute must accept the assessment of the Headquarters on the teaching quality,” a strong incentive for Chinese teachers and directors to take their cues from the Hanban.65

Two of the nine universities included modified stipulations that balanced the assessment authority between the host university and the Hanban. The SUNY Global Center holds that both SUNY and the Hanban “assess the teaching quality of the teachers,” each in a manner “consistent with the practices employed in the parties.”66 At the University at Buffalo, where the CI also oversees several Confucius Classrooms at local K-12 schools, “the Headquarters, the University and the host K-12 schools” each conduct an “assessment of the quality” of CI programs.67

The source of payment is another clue to the authorities at play. Chinese directors, like Chinese teachers, typically maintain contracts and formal arrangements with the Hanban and with their home institution, rather than with the American host university. New Jersey City University identifies suitable apartments for the Chinese director and Chinese teachers, assistant director Tamara Cunningham told us, but the salary, housing and transportation costs are covered by the Hanban.68 The State College of Optometry is contractually obliged to “provide apartments” to Chinese instructors, and presumably other costs are covered by the Hanban or Wenzhou Medical University, the partner university.69 At the University at Buffalo, the contracts specify that the Chinese director’s salary, health insurance, living stipend, and airfare to and from China are covered by either the Hanban or Capital Normal University, the university’s partner institution.70

Chinese Teachers

Chinese teachers, like Chinese directors, are selected by the host university from a pool of candidates nominated by the Chinese partner university and the Hanban. In every Confucius Institute on which we could obtain data, all Chinese teachers who were Chinese natives were paid by the Hanban or the Chinese partner university. Only at Rutgers, where one Chinese teacher is a full-time Rutgers staff member and former professor, does a Chinese teacher’s salary come from the American host institution.

Some university contracts with the Hanban set forth criteria for prospective Chinese teachers. Many contracts state that teachers “should be qualified in English, Chinese Culture, management and coordination abilities.”71

The Hanban has another, more detailed set of criteria, which prospective teachers must pass before they can be nominated to host universities as candidates for Confucius Institute positions. The current eligibility requirements for Chinese teachers, listed on the Hanban’s website, are that Chinese teachers must be healthy, younger than 50 (exceptions for those who speak rare languages), proficient in Chinese and the host institution’s native language, and competent in “teaching, administration and coordination.” Prospective teachers must also be currently employed as a teacher of Chinese or a foreign language, “have Chinese nationality,” and “have strong senses of mission, glory, and responsibility and be conscientious and meticulous in work.”72

Prospective Chinese teachers must meet the Chinese Ministry of Education’s selection requirements (which the Ministry updated in August 2004, just as the Hanban was launching Confucius Institutes).73 Teachers must also attend and pass a two-week training camp run by the Hanban in China.74

In previous years, observers of Confucius Institutes have noted that the Hanban’s eligibility criteria included the stipulation that teachers have “no record of participation in Falun Gong,” a peaceful religious movement banned as “heretical” in China on the pretext that it engages in terrorism.75 Language barring Falun Gong members disappeared from the English version of the Hanban’s website after a Chinese teacher based in Canada accused the Hanban of religious persecution and claimed refugee status in Canada. (See the section “Falun Gong” for more detail.)

Chinese teachers, like Chinese directors, are selected through a two-stage process by the Hanban and by the host institution. The hiring process itself has several layers. Eligible teachers apply either through the Chinese university where they work or through the Hanban, which screens all candidates and nominates prospective teachers to the host institution. There, the CI director, under the auspices of the board, makes the final decision.

In some cases, universities may simply request a teacher, and the Confucius Institute Headquarters will assign someone to fill the role. Paul Manfredi, associate professor of Chinese at Pacific Lutheran University, which does not have a Confucius Institute, requested a teacher from the Confucius Institute at the University of Washington. The university consulted with the Confucius Institute Headquarters, and “they simply found someone and appointed him,” Manfredi said. “There was no participation on our part in selecting the final applicant.” The CI teacher has taught at Pacific Lutheran University for one semester. Manfredi said he was satisfied with the CI teacher, who replaced a teacher formerly funded by the Fulbright Foreign Language Teaching Assistant Program.76

Some people we talked to described a database of pre-screened teachers maintained by the Hanban. When a position at a Confucius Institute opens, the Hanban selects a slate of candidates from which the Confucius Institute can choose. At Pace University, director Joseph Tse-Hei Lee said the Hanban kept a “database of people who are interested in being a CI teacher,” from which a Hanban agent selects two or three resumes to send to CIs in need of staff. As director, Dr. Lee reviews the resumes, interviews the applicants in both English and Chinese, and selects one. If he is dissatisfied with the candidates the Hanban suggests, he can ask for a new set of resumes.77

Tamara Cunningham, assistant director of the CI at New Jersey City University, described the arrangement as a loan of human resources: “The director and teachers are lent by Chinese government from a partner university.”78 Hanban calls itself a “dispatcher” of teachers, a term Xiuli Yin, New Jersey City University’s Chinese Director, repeated in an interview.79 Shijiao Fang, Chinese Director of the Confucius Institute at Stony Brook University and a professor of economics at Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, said Zhongnan “decided” which professors were allowed to apply to the Hanban, which then recommended candidates to the American partner institution.80

Some Confucius Institutes, such as at the University at Buffalo, also oversee local Confucius Classrooms. The Buffalo CI hosts both visiting professors from the Chinese partner university, Capital Normal University, who teach at the university, and also teachers in public K-12 schools. Both sets of teachers sign contracts with the Hanban, said Stephen Dunnett, Vice Provost for International Education at the University at Buffalo and a member of the CI board of directors there.81

Of the nine Confucius Institutes on which we obtained data on hiring practices, all Chinese teachers “dispatched” from the Hanban are paid by the Hanban. Usually, the Hanban covers rent, airfare to and from China, salary, and sometimes health insurance. Dunnett at the University at Buffalo said that the Hanban also “compensates the schools they [the teachers] leave” when they come to foreign countries.82

Only at Rutgers University was a teacher paid by the host institution. One former Rutgers instructor, Dietrich Tschanz, moved to the Confucius Institute as a full-time staff teacher, because he said he wanted to take advantage of the “perks,” such as the free trips to China, that the Confucius Institute provided him.83 Other than Professor Tschanz, every Confucius Institute Chinese teacher we know of at our 12 case studies is paid by either the Hanban or the Chinese sending university.

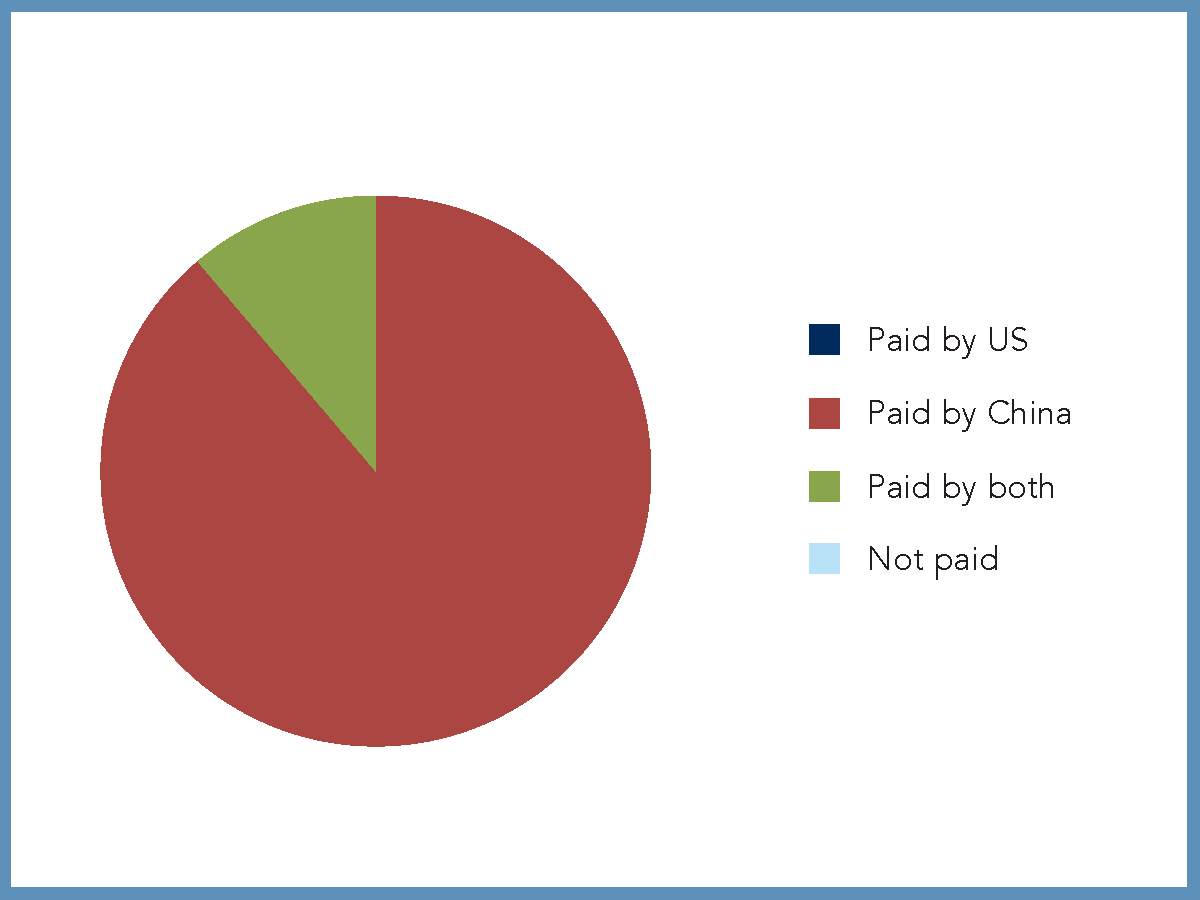

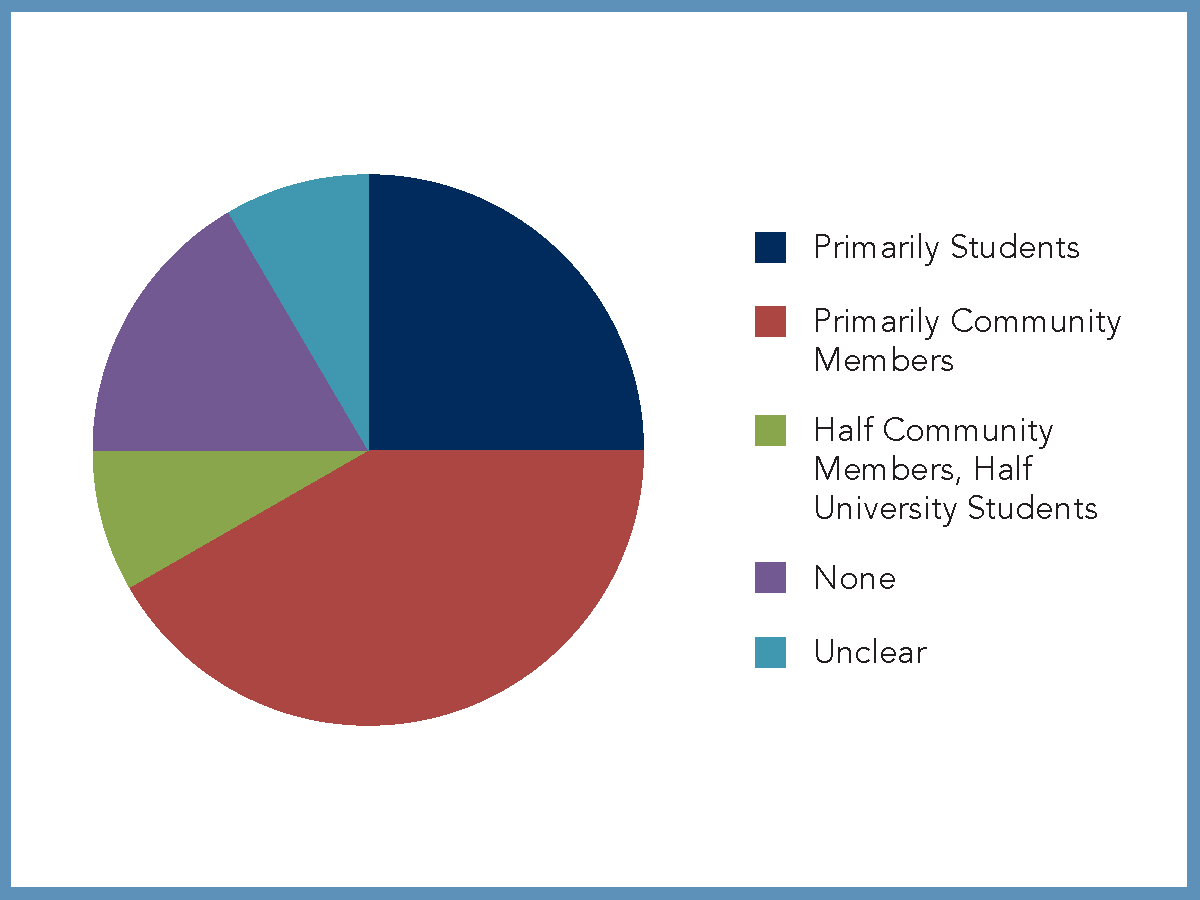

Figure 2 Who Pays Chinese Teachers

Some directors of Confucius Institutes cited their control of the hiring process as evidence that the Hanban does not micromanage its Confucius Institutes, and as confirmation of the host university’s autonomy. The evidence for such autonomy is weak, however, given the Hanban’s role in pre-screening potential applicants and in paying teachers.

At the University at Albany, professors initially were led to believe they would be closely involved in hiring Confucius Institute teachers, said James Hargett, professor of Chinese studies. “The understanding was that we would be involved in the selection of professional teaching Chinese as a second language educators from China, but it didn’t turn out that way,” he said. “We’re not in the process of deciding who to bring. That’s been totally done from the Chinese side.”84

As noted above, we know of only one Confucius Institute teacher who is hired directly by the host university: Dietrich Tschanz at Rutgers. Some CI directors said it was impossible to hire American professors to fill the teaching roles at the Confucius Institutes. E.K. Tan at Stony Brook University cited university transparency guidelines that prevent faculty members from being paid by outside organizations. “We [the Confucius Institute cannot pay an employee on campus,” he said, noting that under Stony Brook rules, “a university professor cannot be paid by a sponsor outside.” Because the CI is funded by the Hanban, no Stony Brook faculty members are eligible for CI positions, unless they agree to take on the responsibilities with no pay, as Tan did.

Other Staff Members

Some CIs have administrative staff hired and paid by the host university. This is the case at Pace University, where the Confucius Institute has a program manager hired by Pace to manage the office, arrange programs, and oversee social media and newsletters in English.85 At the University at Buffalo, the UB Associate Director is a staff member, and therefore a public employee of the state of New York.

University at Buffalo’s contract leaves open the option of hiring a Confucius Institute visiting librarian, to be nominated by Capital Normal University, to catalogue the books provided by the Hanban.86 At Binghamton University, the Confucius Institute periodically works with an affiliated university librarian (an employee of the university) who oversees culture and arts displays in the library foyer.

CIs that have been established for at least two years with at least 200 registered students may add the position of “Head Teacher” to oversee the teachers and develop lesson plans and resources.87 The Hanban requires that the Head Teacher must meet the additional requirements of having “overall capacities such as cross-cultural communication and organizational skills,” and either two years of experience teaching at a Confucius Institute or five years of experience teaching Chinese in other settings.88

The Head Teacher, unlike the other Chinese teachers, should sign a contract with the host institution itself, which also must agree to provide health insurance and other benefits, and to share the cost of the Head Teacher’s salary with the Hanban. The host university has the authority to assess the teacher each year, but must include in its assessment the Hanban’s comments on the teacher’s performance. Both the host institution and the Hanban have the authority to fire the Head Teacher for breach of rules, including “Violation of the laws of the host country (region) or China.”89 None of the 12 CIs we examined had a Head Teacher.

Hanban’s Selection Process

Defenders of Confucius Institutes say the Hanban’s role in the hiring process is simply a matter of quality control. In this reading, the Hanban’s criteria ensure that Chinese teachers have the basic skills and language proficiency to succeed, rather than filtering candidates by ideology, religion, or loyalty. In our research, we found no evidence that Chinese teachers in Confucius Institutes act as automaton promoters of the Chinese government or the Chinese Communist Party.

But there is evidence that the Hanban has included litmus tests in screening applicant teachers, for instance, excluding those who practice Falun Gong. And we found in our interviews and research that some teachers felt pressure, ranging from implicit requests to explicit demands, to avoid conversations that would embarrass the Chinese regime or undermine its credibility. (This is discussed in more detail in the “Academic Freedom” section.)