Introduction

In the 1950s, a constellation of philanthropic foundations, multinational corporations, interested scholars, and the U.S. government established the first Middle East Studies Centers (MESC) as part of an effort to improve national security during the Cold War. These centers belonged to a class of newly created academic units called “area studies,” which grouped scholars together by a geographic area of focus rather than by discipline. The founders of these centers intended to shift research and instruction away from ancient history and languages and toward the modern Middle East. They encouraged academics to produce policy-relevant information that benefited the American national interest. Centers also trained students in the languages of the region so that their alumni could work for the government as liaisons in this strategically important area.1

In the aftermath of the Six-Day War (1967) and the Yom Kippur War (1973), whose outcomes turned significantly upon American diplomatic and military support for Israel, wealthy Arab nations realized these centers could be useful tools to influence American policy in the region.

In 1975, Georgetown University academics and administrators collaborated with government officials from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Oman, and Libya to establish Georgetown’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies (CCAS). Critics quickly accused the center of propagandizing for their foreign sponsors instead of pursuing disinterested academic study and serving the American national interest.

Concerns over Georgetown’s CCAS prompted Congress to include a foreign donation disclosure requirement in the Higher Education Amendments of 1986. Proponents of this provision believed that a transparency mandate would at least increase public awareness of the extent and nature of foreign influence, even if it failed to stop it entirely. The Department of Education (ED) rarely enforced this requirement until the Trump administration initiated investigations into several prominent universities in 2019. These investigations prompted universities to back-report more than $6.5 billion in foreign donations. Many of the donations came from governments, institutions, and individuals from Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Concerns over foreign influence generated the bulk of public interest in MESCs over the last two generations. This report is no exception. We began this project to provide an up-to-date and comprehensive account of the history, character, and structure of the centers and to uncover the degree to which foreign funding has corrupted the study of the Middle East.

Previous investigations of the centers found few smoking guns to link foreign funding to the alteration of academic content, but they revealed a troubling pattern of bias, obfuscation, and opacity in the centers’ policies and finances. Our report finds that MESCs still suffer from endemic bias, obfuscation, and opacity to this day. We also discover and explain two far more worrisome developments:

- Centers with little to no foreign involvement teach and research with the same extensive bias as those with significant foreign involvement.

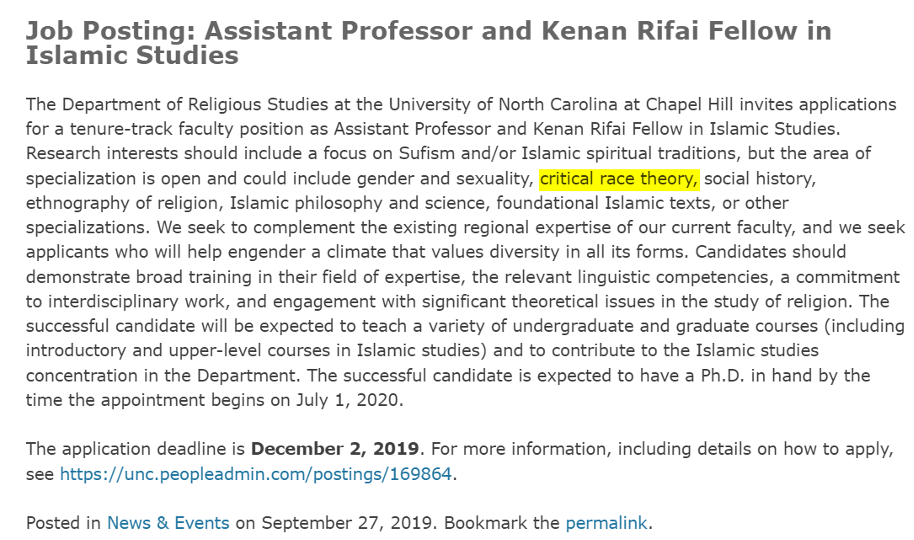

- Foreign governments typically do not fund the most harmful materials produced by the centers, such as critical race theory (CRT) workshops for local K–12 educators. Instead, the U.S. government subsidizes these materials through Title VI of the Higher Education Act.

In other words, the same leftist hysteria which has consumed the humanities and social sciences since the 1960s has spread to MESCs—subsidized by American taxpayer dollars. Academics have repurposed critical theory to galvanize activism on Middle East issues. For instance, they have recast the Israel–Palestine debate as a fight for “indigenous rights” against the supposed evils of colonialism.

Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) became the basis for justifying the application of critical theory to Middle East studies. Said transposed the philosophy of critical theorists such as Frantz Fanon and Michel Foucault onto relations between the Eastern and Western worlds, establishing the neo-Marxist framework that underlies much of the scholarship in the field today. Though Said was not a Middle East studies professor himself, his analysis severely damaged the content and structure of Middle East studies for decades to come.

Said’s framework enabled subjectivity to dominate the study of the Middle East. Centers now focus on notions such as “taking back our stories,” propping up select Middle Eastern groups who putatively suffer from “Western oppression,” and dismissing any criticism of these groups as biased. In fact, they explicitly eschew most criticism of the various cultures, religions, and ethnicities in the region—with Israelis as the notable exception. Affiliated faculty agitate for political causes in their instruction and research, as well as in the outreach materials they create for the local community.

Certain Middle Eastern governments and their representatives clearly benefit from the activities conducted at these centers. The centers aim to dismantle all negative perceptions of Muslims, Arabs, and other Middle Eastern groups.

It is no surprise that foreign governments and individuals fund these centers. But foreign sponsors rarely need to exercise active influence, for the faculty and staff willingly do their bidding unasked. Donors can thus take a hands-off approach, leaving almost no paper trail other than a dollar amount and a few signatures. The funding still serves their interests: continued production of biased material that promotes the political interests of the donors.

Some funds from Middle Eastern donors are not political in nature and support benign projects such as scientific research. But without transparency, it is difficult for Americans to understand the nature of foreign funds to universities.

This report aims to clarify the complex interplay between foreign governments, the U.S. government, private foundations, and scholars at these centers. Figure 1 lists all American Middle East Studies Centers. We provide the necessary historical context to explain how homegrown radicalism in American universities led prominent Middle East scholars to willingly promote the interests of foreign, often anti-American, groups. We demonstrate how foreign governments took advantage of these academics’ ideological commitment over the decades to propagandize Americans. We also show that the scholars are more loyal to their ideologies than to the foreign governments, which explains the apparent tension between their views and those of their foreign sponsors on certain social and political issues. Finally, we examine how the federal government has subsidized harmful material through the centers in recent years.

The corruption of these centers, however, does not mean that we should eliminate the study of the Arab world. Prior to the establishment of these centers, American scholars accomplished important feats through their study of the Middle East, such as the authentication of the Dead Sea Scrolls and discoveries of Sumerian cuneiform tablets.2 American scholars continue to make major contributions in archeology, and American institutional sponsorship (and Bahraini subsidy) makes possible such fine contributions as the New York University Press’ Library of Arabic Literature. Even now, the centers still teach some useful knowledge. They shine particularly in their language instruction, where students can learn both modern and ancient languages.

Scholars increasingly preoccupied with social justice activism, however, cheapen the quality of instruction. Serious changes must be made to restore the rigorous study of Islam and the Middle East. When Middle East studies returns to its roots, American students will receive the robust Middle East education that they desire—and that American taxpayers deserve.

Figure 1: American Middle East Studies Centers3

|

School |

Name of Center/Institute |

|---|---|

|

Boston University |

Institute for the Study of Muslim Societies and Civilizations |

|

Brandeis University |

Crown Center for Middle East Studies |

|

Brown University |

Center for Middle East Studies |

|

California State University at San Bernardino |

Center for the Study of Muslim & Arab Worlds |

|

Columbia University |

Center for Palestine Studies |

|

Columbia University |

Sakıp Sabancı Center for Turkish Studies |

|

Columbia University |

Middle East Institute |

|

Duke University-University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

North Carolina Consortium for Middle East Studies |

|

Florida State University |

Middle East Center |

|

George Mason University |

AbuSulayman Center for Global Islamic Studies |

|

George Washington University |

Institute for Middle East Studies |

|

Georgetown University |

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies |

|

Georgetown University |

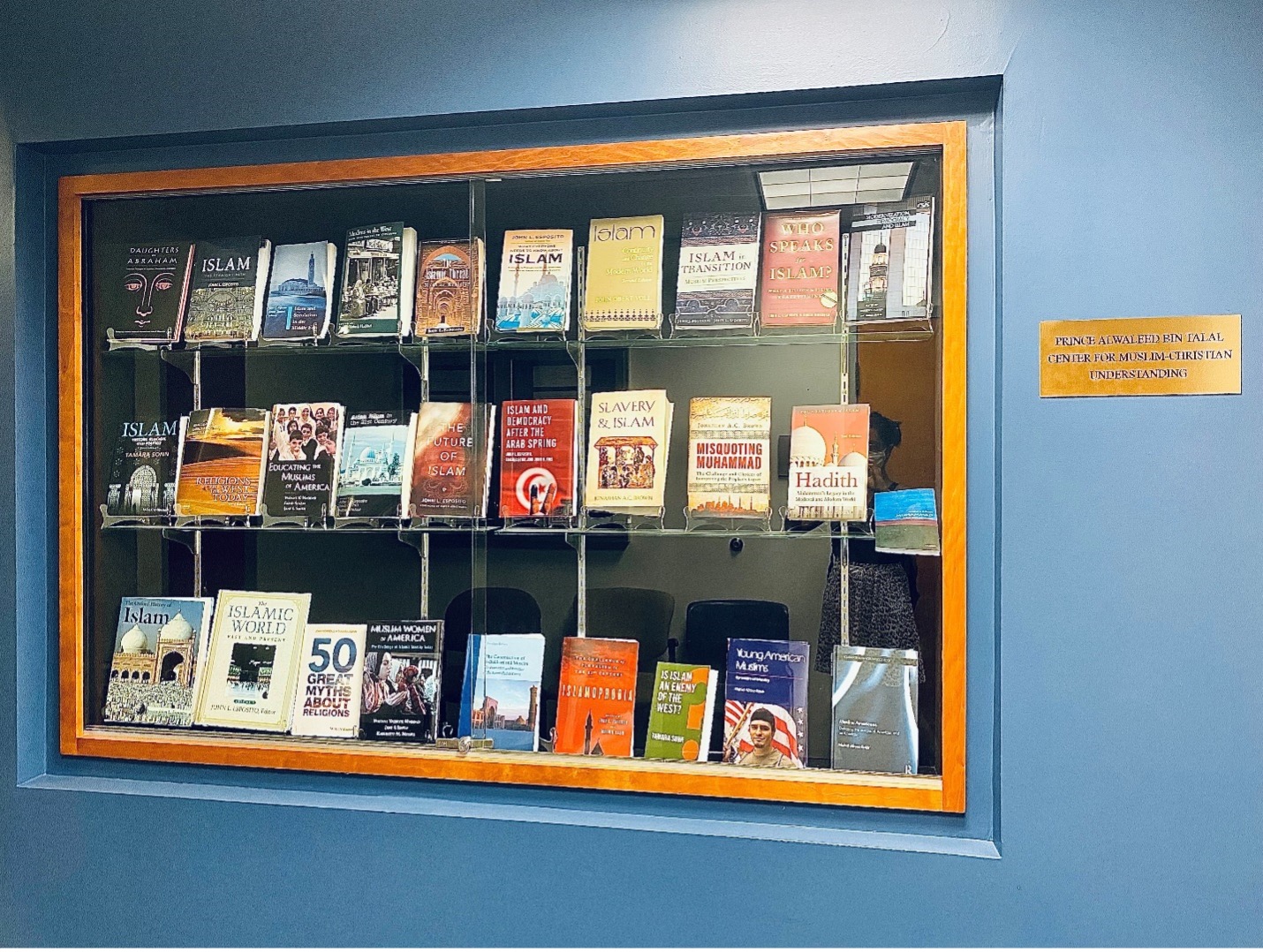

Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding |

|

Harvard University |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies |

|

Harvard University |

Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Islamic Studies Program |

|

Harvard University |

Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture |

|

Indiana University Bloomington |

Center for the Study of the Middle East |

|

Lehigh University |

Center for Global Islamic Studies |

|

Merrimack College |

Center for the Study of Jewish-Christian-Muslim Relations |

|

New York University |

Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies |

|

Northeastern University |

Middle East Center |

|

Northwestern University |

Institute for the Study of Islamic Thought in Africa |

|

The Ohio State University |

Middle East Studies Center |

|

Portland State University |

Middle East Studies Center |

|

Princeton University |

The Institute for the Transregional Study of the Contemporary Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia |

|

Rutgers University |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies |

|

San Diego State University |

Center for Islamic and Arabic Studies |

|

Shenandoah University |

Center for Islam in the Contemporary World |

|

St. Bonaventure University |

Center for Arab and Islamic Studies |

|

Tufts University |

Fares Center for Eastern Mediterranean Studies |

|

University of Arizona |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies |

|

University of Arizona |

School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies |

|

University of Arizona |

American Institute for Maghrib Studies |

|

University of Arkansas |

King Fahd Center for Middle East Studies |

|

University of California at Berkeley |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies |

|

University of California at Irvine |

Samuel Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture |

|

University of California at Los Angeles |

Center for Near Eastern Studies |

|

University of California at Santa Barbara |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies |

|

University of Chicago |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies |

|

University of Denver |

Center for Middle East Studies |

|

University of Florida |

Center for Global Islamic Studies |

|

University of Illinois |

Center for South Asian & Middle Eastern Studies |

|

University of Maryland |

Roshan Institute for Persian Studies |

|

University of Michigan |

Center for Middle Eastern and North African Studies |

|

University of Oklahoma |

Center for Middle East Studies |

|

University of Pennsylvania |

Middle East Center |

|

University of Texas at Austin |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies |

|

University of Utah |

Middle East Center |

|

University of Washington |

Middle East Center |

|

Villanova University |

Center for Arab and Islamic Studies |

|

Washington University in St. Louis |

Jewish, Islamic, and Middle Eastern Studies |

|

Yale University |

Council on Middle East Studies |

|

Yale University |

Abdallah S. Kamel Center for the Study of Islamic Law and Civilization |

Methods

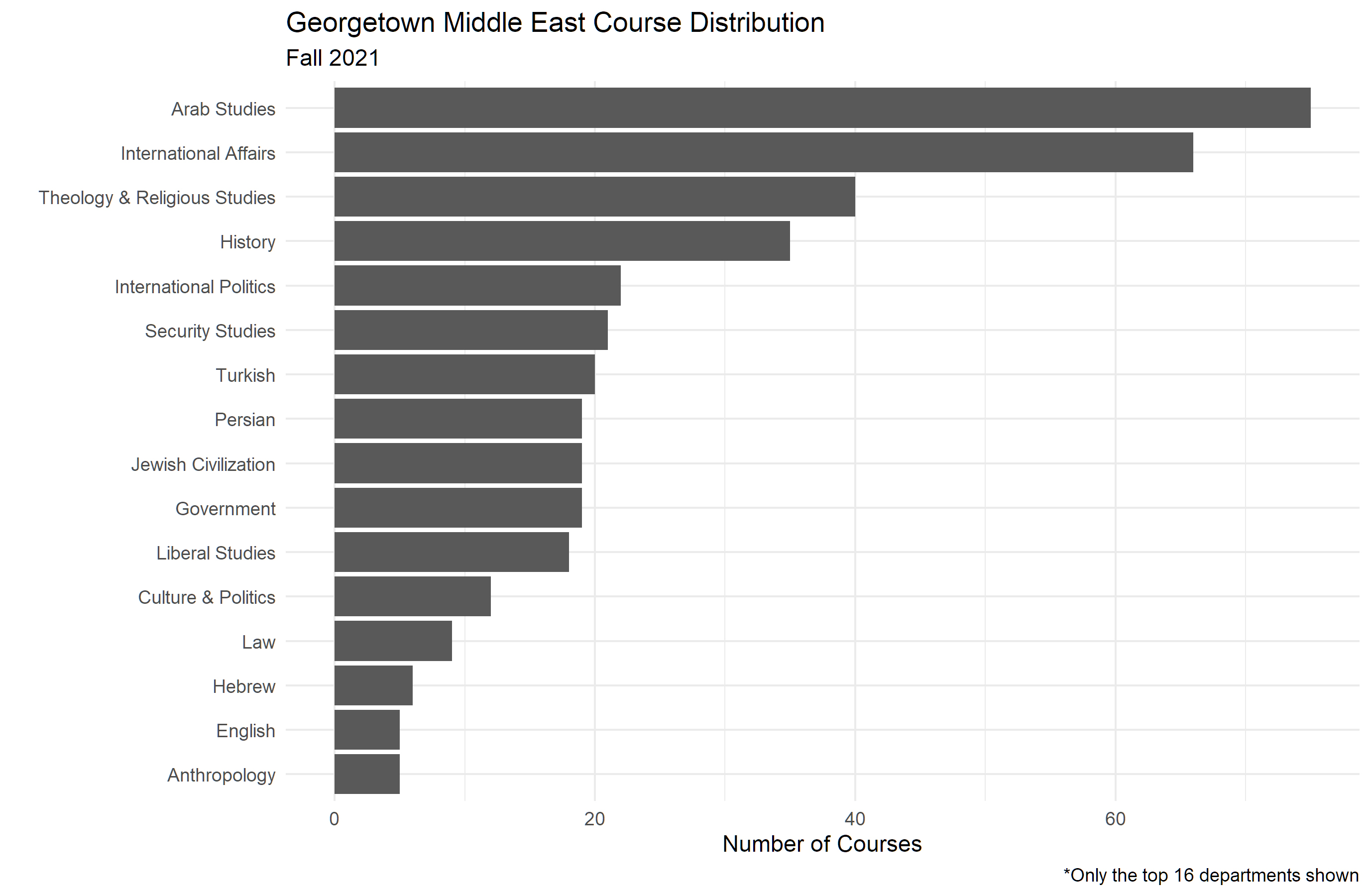

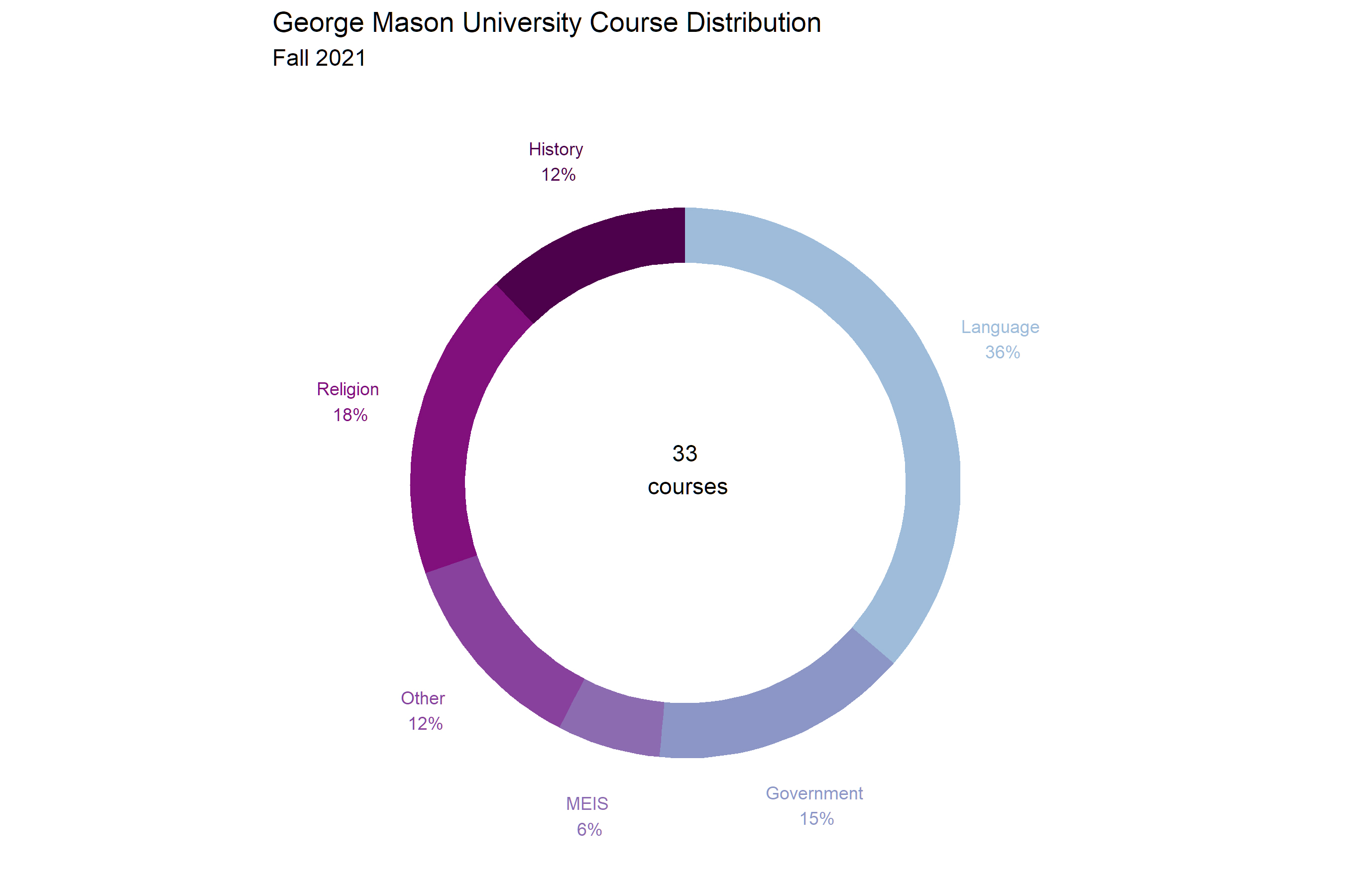

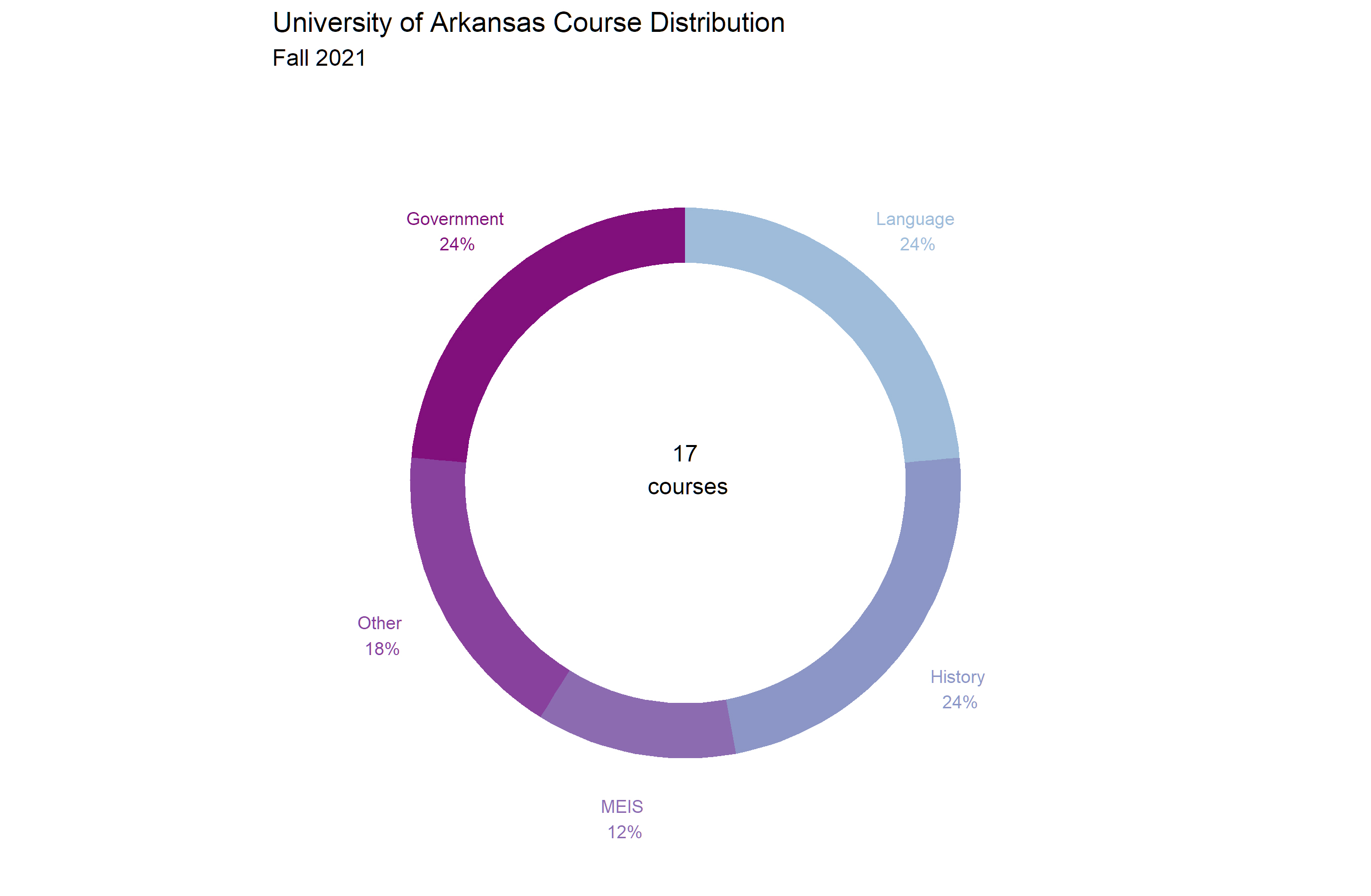

More than 50 academic centers in the U.S. focus on some aspect of the Islamic world. We provide in-depth information through case studies of Middle East and/or Islamic studies centers at eight universities: Harvard University, Georgetown University, George Mason University, University of Arkansas, Duke University/University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Consortium, University of Texas at Austin, and Yale University.

Figure 2: Our Case Studies

|

Institution Name |

Units |

Year First Unit was Founded |

|---|---|---|

|

Harvard University |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies; Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Islamic Studies Program; Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture |

1954 |

|

University of Texas-Austin |

Center for Middle Eastern Studies |

1960 |

|

Yale University |

Council on Middle East Studies; Abdallah S. Kamel Center for the Study of Islamic Law and Civilization |

1970 |

|

Georgetown University |

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies; Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding |

1975 |

|

University of Arkansas |

King Fahd Center for Middle East Studies |

1993 |

|

Duke University/University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill |

North Carolina Consortium for Middle East Studies |

2005 |

|

George Mason University |

AbuSulayman Center for Global Islamic Studies |

2009 |

As of 2022, Duke-UNC has a National Resource Centers (NRCs), a special designation that allows universities to receive federal funds. UT-Austin and Yale had NRCs up until the 2022-2025 funding cycle. The University of Arkansas, Harvard, and George Mason do not have NRCs. Georgetown has a combination of NRCs and non-NRCs. The mixture of NRCs and non-NRCs enables us to compare whether federal funds make any difference in the activities of the centers.

Each case study in our report will include a general history of the centers and a detailed investigation into the extent of foreign donations. This will be particularly useful for scholars and policymakers who wish to understand the basic facts about these centers. We also address a literature gap by providing in-depth histories aggregated in one place. The histories, especially of the financial support for each center, offer Americans an understanding of each center’s fundraising strategy today. Case study lengths will vary, based on the information that was publicly available and information the author gained through interviews.

Our case studies provide an even mix of public and private universities. Harvard, Yale, Duke, and Georgetown are all private and prestigious universities that attract major foreign donations and headlines. In the past decade, Harvard, Georgetown, and Yale have received prominent media attention for their foreign donations. Our analysis goes beyond the headlines to provide an in-depth analysis of outreach and course materials at these elite institutions.

It is equally important to observe how public institutions benefit from foreign funds. These institutions are frequently overlooked, since public attention often focuses on their elite, private counterparts. But, as this report details, public universities also engage in opaque financial practices. More students attend public four-year universities than private ones, and thus bring in more federal funds through student aid. Public institutions which fail to provide transparency in finances and operations fail their students and the states which give them additional funding outside of federal support.

Our investigation intentionally includes centers supported by donations that originated from different countries. Prior studies have focused on Saudi Arabian funds, which account for a majority of foreign donations to American universities. Our research considers two universities which benefited substantially from non-Saudi donations. Georgetown’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies received a hodge-podge of gifts from the UAE, Oman, and Libya during the 1970s, and George Mason’s Center for Global Islamic Studies heavily relied on donations from Turkish businessman Ali Vural Ak, in 2009. Regardless of the originating country, it is vital to assess whether foreign funds affect the academic focus of individual centers or university courses.

In addition to the case studies, our study analyzes both the content that MESCs produce and the financial systems that enable them to operate. We base our findings on an examination of financial data, course syllabi, and interviews with administrators, faculty, and students. We also use archived materials to provide insight into the reasons why these centers were established in the first place. We are also the first, to our knowledge, to provide a broader overview of all Middle East NRCs between academic years 2000 and 2019 based on information from the International Resource Information System (IRIS).

We offer five recommendations, subdivided into two categories:

I. Federal Proposals

- Public university foundations should be subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, while protecting the anonymity of domestic donors.

- The Department of Education should require universities to report all foreign donations prior to the 2019 guidance.

- The federal government should consider withdrawing financial support for National Resource Centers.

II. University Proposals

- Universities should publish details about contracts, memoranda of understanding, and other deals with foreign countries in an easily accessible location on their websites.

- Advisory boards for MESCs should not include members who represent the interests of a foreign country.

Origins & Purpose

The American discipline of Middle East studies was born out of a Western impulse to understand the region, its culture, and its people. Some were captivated by intellectual curiosity: from Jean-François Champollion’s decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics to Richard Francis Burton’s translation of the One Thousand and One Nights. In other instances, the impulse to study the Middle East was driven by the imperial pursuits of English and French scholars.

Any thorough study of Middle East education requires a historical analysis of the academic and external contexts in which the field developed. We must understand how developments inside and outside of academia have shaped the discipline of Middle East studies, especially over the past several decades, to accurately interpret the current behavior of MESCs. The past, more importantly, provides a standard of comparison by which we can assess the current quality and ideological bent of Middle East education.

|

What’s in a Name? The discipline of Middle East studies typically focuses on the modern development, culture, and people of present-day countries in the Middle East, including but not limited to Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, and Egypt. But the region was not always called the “Middle East.” The most antiquated term is the “Orient,” which referred to countries in the Islamic world and Asia. The terms “Near East” and “Far East,” however, were later used to denote the difference between the two areas.4 In our report, we use the term “Middle East” throughout, as this is the most common way to refer to the region today. |

New Beginnings (1600–1880s)

In America, the formal study of the Middle East can be traced as far back as the 1600s. Harvard University was the first higher education institution in the new commonwealth to teach Semitic and Arabic languages, mainly for the purposes of biblical exegesis.5 Other colonial colleges followed Harvard’s example: Yale University introduced Arabic in 1700, the University of Pennsylvania in 1788, Andover Theological Seminary and Dartmouth College in 1807, and Princeton University in 1822.6

Academic and public interest in the region grew significantly after Napoleon discovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799.7 In the aftermath of the Great Awakenings, many American churches launched efforts to evangelize the Islamic world. The missionaries, who were often graduates of universities such as Yale, Dartmouth, and Princeton, gained a first-hand understanding of the region and its people.8 The missionaries’ primary purpose was evangelical, but their contributions in education proved to be vital to the development of Middle East studies in America.

In the 1860s, the missionaries established the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut, Lebanon (renamed the American University of Beirut in 1920) and Robert College in Istanbul, Turkey.9 Decades later, when American political objectives in the Middle East began to expand, scholars at these institutions lent their expertise in the region to both political and academic pursuits.

A Time of Transition (1880–1940)

American universities expanded their curricula to incorporate several new fields at the turn of the 20th century. American industrialists such as Johns Hopkins, Andrew Carnegie, and John Rockefeller spearheaded these endeavors and established well-funded educational institutions. Smaller donors, meanwhile, eagerly looked to sponsor research projects. This era of expansion led to a new approach in Middle East studies and research that extended beyond the earlier emphasis on Semitic languages and religious texts.10

Donors sought to sponsor attention-grabbing projects that would have practical results, which encouraged researchers to depart from the classical style of scholarship.11 In the early 1880s, the American Oriental Society (AOS) organized the first American archaeological expedition to ancient Babylon and Assyria to collect interesting artifacts to display back home.12 The AOS’s successful mission inspired others in higher education to conduct excavations of their own. The University of Pennsylvania organized a trip to Sumer, from which researchers recovered and translated many cuneiform tablets. The University of California, Berkeley, meanwhile, led digs in the Egyptian town of Qift and established an anthropology department at the turn of the 20th century.

The American public became increasingly interested in studying Middle Eastern languages and cultures in the first half of the 20th century. Social and geopolitical developments, such as Britain’s discovery of oil in Persia and the burgeoning Zionist movement among recent Jewish immigrants, likely contributed to the increased public interest.13 But America’s infrastructure for Middle East education was highly underdeveloped at the time and was not immediately prepared to meet the increased interest.

Two leading figures would change that: archeologist James Henry Breasted and professor Philip Hitti.

The University of Chicago hired Breasted as a lecturer in 1905 after he returned from studying Egyptology in Germany.14 During Breasted’s tenure, the Ottoman Empire’s collapse presented archaeologists with an array of new opportunities in lands now under European control. Breasted used his connection to the oil-wealthy Rockefeller family to launch a massive archeological expedition in the Middle East. Breasted’s expedition and his subsequent tenure as director of the Oriental Institute established the University of Chicago as one of the foremost hubs for Middle East scholarship prior to World War II. His connection with the Rockefellers also ushered in an era of significant Rockefeller funding for Middle East research.15

The second mover and shaker in Middle East scholarship in the interwar period was Philip Hitti, a young Lebanese professor who studied at both Columbia and the missionary-founded Syrian Protestant College. In 1926, Princeton recruited Hitti and appointed him as an assistant professor of Semitic philology. Princeton had a glut of untranslated manuscripts from previous archaeological expeditions at the time. Hitti seemed the perfect choice to make use of the findings. Hitti proceeded to assemble a group of scholars at Princeton to study Semitic languages and literature, and through his work, he almost single-handedly established Arabic studies in its modern form.16

Many orientalists continued down the path forged by Breasted and Hitti, studying Semitic philology and applying the knowledge to archeology and anthropology. The motivation for studying the region varied from scholar to scholar. Some scholars undoubtedly desired to catch up with European scholars, who had pioneered the academic study of the Middle East. Others had an academic interest in uncovering the connections that linked the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt with those of Greece and Rome.17

Whatever the motivations of individual scholars, Semitic studies and archaeology ultimately served as the precursors to modern Middle East area studies. The field’s roots significantly influenced its development: the early emphasis on archaeology over anthropology shaped how American scholars studied the Middle East for many years. Archaeologists focused on the region’s distant past, whereas anthropologists were more interested in studying contemporary Middle Easterners. With archaeologists at the helm, the field of Middle East studies was thus more concerned with the history of the region and its people than with contemporary political and social issues.

When the region became politically significant during World War II, the entire field of contemporary Middle East studies was reoriented to serve America’s political interests. Much of the excitement surrounding Middle East studies during the first quarter of the century had slowed down once the Great Depression began in the 1930s. Funding—even from the wealthy Rockefellers—had dried up, and many scholars had become desperate for work. When the government came knocking during World War II, archaeologists, linguists, anthropologists, and other academics eagerly joined the cause.18

New Power, New Problems (1940–1990)

The period between World War II and the end of the Cold War witnessed major developments in American Middle East studies—with decidedly mixed effects. On the one hand, scholars’ careful work during those years led to many great discoveries and academic contributions, including the translation of the Dead Sea Scrolls; continued archaeological expeditions in Turkey, Iraq, and Iran; and new research on pre-Islamic sites.19 But the period also introduced significant government entanglement into the study of the Middle East, which has had a lasting effect on the discipline.

In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the CIA’s precursor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The OSS recruited scholars to gather information on foreign nations with which the United States was currently involved or anticipated future involvement. The Near East division of the OSS, however, quickly discovered that most researchers were unfamiliar with modern political affairs in the region. As future Middle East studies director for the University of Pennsylvania E.A. Speiser put it, “It was not unusual for an Egyptologist to serve as an Arab affairs specialist or for a cuneiformist to investigate the manifold problems in Afghanistan.”20

The federal government and a plethora of external organizations had realized that more Americans needed to receive a robust education in modern world affairs by the end of World War II. The OSS’s structure, which had had divisions based on world region, provided the blueprint for modern area studies in academia.21

But it was the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) and its affiliates who first advocated, in 1947, for a “national program for area studies” that would encompass knowledge about the entire world.22 Two years later, the SSRC’s humanities counterpart, the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS), noted the lack of American academic expertise on the contemporary Middle East.23

The Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation, which had close ties to the SSRC and ACLS, were also interested in funding area studies. The Cold War prompted them to focus initially on sponsoring research on Russia and East Asia. But after Israel secured its independence in 1948, and with an eye to the Middle East as a site of existing and potential Cold War conflict, Rockefeller and Carnegie turned their attention to the lands between Casablanca and Kabul.

Modern Middle East studies faced several challenges in its early days. First, it was not easy to reorient a field that had historically focused on producing more traditional scholarship toward scholarship that supported the American government’s strategic political aims. John Wilson tried to push through such a transformation at the University of Chicago in the mid 1940s, but he was forced to scrap the project due to heavy resistance from other scholars.24 Government interference with academic research was also a major concern, especially in the years following the creation of the CIA in 1947. Some academics were quite enthusiastic about the new funding and research opportunities that partnership with the CIA presented.25 Others, however, feared that the agency’s involvement in higher education would compromise the integrity of the academic research conducted in American universities.26

Regardless of these concerns, the field of Middle East studies proceeded to develop and expand in the following years. Philip Hitti managed to transform Princeton’s Department of Oriental Studies from traditional to modern scholarship, and Princeton provided the blueprint for future Middle East area studies departments.27 Many of the early leaders in Middle East studies secured new opportunities for their departments by maintaining connections with the CIA.

Figure 3: Middle East Scholars’ Connections to Intelligence Agencies

|

Name |

Role(s) |

OSS? |

CIA? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

William Langer |

Director of Harvard’s Center for Middle East Studies |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Richard Frye |

Helped create Harvard’s Center for Middle East Studies; Chair of Iranian Studies |

Yes |

Not confirmed |

|

Nadav Safran |

Director of Harvard’s Center for Middle East Studies |

No |

Yes |

|

T. Cuyler Young |

Chairman of Princeton’s Department of Oriental Studies |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Morroe Berger |

Director of Princeton’s program in Near Eastern Studies |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Ephraim Avigdor Speiser |

Chairman of the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Oriental Studies |

Yes |

Not Confirmed |

|

Carleton Coon |

Professor at the University of Pennsylvania |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Franz Rosenthal |

Yale’s Louis M. Rabinowitz professor of Semitic languages |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Walter L. Wright |

Turkish Language and History Professor at Princeton |

Yes |

Not Confirmed |

|

Lewis V. Thomas |

Professor of Oriental Studies at Princeton |

Yes |

Not Confirmed |

The first Middle East Studies Centers in America received much of their funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation. In the 1950s, the Ford Foundation became one of the primary funders of MESCs as well. Because these private organizations enjoyed close relationships with the government, it is difficult to say whether MESCs were privately or publicly funded in those days. The Ford Foundation (technically a private foundation), for example, actively collaborated with the CIA and appointed a three-person board to funnel CIA funds through its organization to desired targets. Between 1959 and 1963, the Ford Foundation gave $42 million in donations to fifteen universities, with 60% dedicated to area studies and language education.28

Congress soon became interested in these Middle East studies programs. In 1958, Congress passed the National Defense in Education Act (NDEA), an emergency Cold War measure designed to support education initiatives that assisted America’s national defense. As President Eisenhower noted:

The American people generally are deficient in foreign languages, particularly those of the emerging nations in Asia, Africa, and the Near East. It is important to our national security that such deficiencies be promptly overcome.29

In its first year, the NDEA established nineteen National Resource Centers (NRCs), three of which were devoted to the Middle East. The NRCs provided education about a region’s culture and politics. NRCs also offered instruction in “critical languages,” which included Arabic, Hindi-Urdu, Russian, Japanese, Portuguese, and Chinese.30 The government encouraged the NRCs to bring in social scientists, such as anthropologists, political scientists, sociologists, and economists, to aid with the instruction and research conducted at the centers. The inclusion of social scientists reinforced the private foundations’ goals of producing practical, policy-relevant information about the region.

MESCs quickly supplied the deficit of scholars in the field. But they also became hotbeds of political controversy. Not everybody supported Israel’s independence, for example, and fierce debates broke out between scholars at centers across the country. Many prominent figures, such as Philip Hitti and William Wright, vocally supported the Arab contenders. Others, such as William Brinner (who later became president of the Middle East Studies Association), firmly supported Israel. The controversy only increased throughout the 1950s, which saw both the CIA-backed Iranian coup and the Suez Crisis. The temperature of these scholarly quarrels at last reached a boiling point in the wake of the Six-Day War in 1967. The Middle East Studies Association (MESA) was formed partially with the goal of resolving the field’s political rifts.31

It did not, however, prevent continuing radicalization of MESCs in the 1960s and 1970s. Pro-Palestinian pressure emerged from the growing New Left movement in academia, driven by student activist groups such as Students for a Democratic Society. The New Left drew its inspiration from critical theorists of the 1930s and 1940s such as Herbert Marcuse and Max Horkheimer, and later it was greatly influenced by thinkers such as Frantz Fanon and Michel Foucault.32 These New Left thinkers not only provided the intellectual foundation for the sexual revolution of the 1960s but also inspired both the decolonization movement and its “postcolonial” successor.33

At first, New Left students (and, in time, professors) primarily supported African decolonization in states such as Algeria. The decolonization movement, though, adopted a broader stance as the 1960s and 1970s progressed.34 Students began to criticize American interventions in the Third World and launched an extensive campaign against the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. Postcolonial thinkers soon turned their attention to the conflict between Israel and Palestine, in which they compared Israel’s expansion in the region to previous European colonial empires around the world.35 Although European and American support in the late 1940s for the establishment of Israel was strongest among the radical left, within a generation the European and American radical left became the most virulent critics of Israel in the Western world. Supporters of the decolonization movement also criticized U.S. economic and military interventions in the Middle East as neocolonialist actions motivated by the desire to secure American access to oil.

MESCs acquiesced in the extension of the new postmodernist thought throughout their discipline. Partly they believed they could not exclude the New Left, which provided such a large proportion of the younger cohort of scholars.

Perhaps more importantly, in 1975, the Church Committee exposed the shocking activities of the CIA and its affiliates such as the Ford Foundation, which included covert funding of academic research.36 The findings created a rift between academics and the CIA, which led the CIA and its affiliates to significantly decrease their support of and involvement with American academic centers.

The New Left soon received major intellectual reinforcements. In 1978, Palestinian-American literature professor Edward Said published his seminal work Orientalism, which provided a scathing philosophical critique of Western perceptions of the nations of the Orient.37 Said was strongly influenced by thinkers such as Foucault and Fanon and drew his methodology from the critical theory of Theodor Adorno and the Frankfurt School.38 His work strove to discredit the Orientalist approach of the early scholars at MESCs, and the resulting controversy caused another major rift in the field. Older scholars such as British historian Bernard Lewis, who later served as doctoral advisor to Middle East studies critic Martin Kramer, strongly critiqued Said’s work and his dismissal of the existing scholarship on the Middle East as the biased handmaiden of European imperial power—but Said’s school of thought ultimately emerged victorious among American Middle East scholars. Lewis, though well-connected politically and a sought-after advisor during the Bush administration of 2001-2009, became a pariah in the field.39 Said’s book continues to influence most Middle East scholars today, and it has inspired many similar critiques of Western perceptions of other parts of the world.

Amid this broader philosophical shift, many scholars within the field of Middle East studies began to engage in more explicit political activism on behalf of Palestine. As immigration from Middle Eastern nations increased, MESCs welcomed a growing number of Arabic scholars and students, many of whom brought local political ambitions and grievances with them to the field. The new scholars’ penchant for activism only increased the existing enmity between the political establishment and the academics, which had begun to set in after the Church Committee’s revelation of the extent of CIA involvement in the field.

It became highly unpopular for academics to work with the CIA. For example, Harvard’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies director Nadav Safran failed to report CIA funds for an academic conference in 1985 on Islamic fundamentalism. Harvard’s CMES received significant criticism, and Safran eventually resigned from the center, though he remained a professor at the university.40

Ironically, a major American Middle Eastern foreign policy triumph occurred just as academics began to disengage themselves from the CIA. The Reagan administration partnered with Saudi and Pakistani intelligence to arm Islamist Afghan rebels in the fight against the Soviets, and the consequent Soviet–Afghan War served as the final proxy battle of the Cold War. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) went so far as to publish and disseminate jihadist textbooks to the Afghan rebels, which remained in use for years to come.41 America’s adroit support for the Afghan rebels played a central role in bringing about a victory beyond the dreams of most American policymakers: the collapse of the Soviet Union.

That victory created a new range of facts on the ground in the Middle East, which would set the agenda for the next generation of MESCs—above all, how to address anti-Western Islamic sentiment and Islamist terrorism, both within the Middle East itself and among the Middle Eastern diasporas of Europe and America.42

Reinvention (1990–Present)

Americans generally greeted the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War with joy and relief. Yet the end of the Cold War also ended the primary rationale for government funding of MESCs, which now faced a financial crisis. Directors worried that the centers might be headed toward dissolution if they could not find a new purpose.43

To make matters worse, many Americans began to look upon the Arab world with suspicion. The 1973 oil crisis was still an unpleasant memory, while the 1979 Iranian Revolution, along with the resulting hostage crisis, evoked further concerns about the anti-Americanism of Middle Eastern nations. American citizens, in addition, were growing aware of the specific dangers posed by Islamic fundamentalism. The Islamic militants who committed the 1993 World Trade Center bombing were revealed to be disciples of a sheikh who had been brought to the U.S. by the CIA due to his assistance in the Soviet–Afghan War.44 Fears of Islamic radicalism multiplied following the attack, and Middle East scholars grew concerned about the possible repercussions for the discipline and for the Arab world.

Concern about backlash against Arab peoples dominated most Middle East scholars’ responses to pre-9/11 Islamic terrorism. The field’s understanding of contemporary history came to be shaped by its grievances against American foreign policy, whether Palestinian, Iranian, or otherwise. Other critics of MESCs, such as Martin Kramer, have noted the same patterns and wrote critiques of the grievance-oriented approach to studying the region. As a result of their obsession with criticizing American foreign policy, Middle East scholars have consistently downplayed the influence of Islamist leaders such as Osama bin Laden, an approach which Kramer argues has left the U.S. vulnerable to terrorist attacks.45

On the other hand, Middle East scholars did warn with some accuracy of the possibility of a large-scale war in the Middle East, and of untoward consequences that might follow from such a conflict. Middle East scholars tended to believe that America (perhaps prompted by Israel) simply sought a pretext for neo-colonial adventurism in the Middle East to revitalize the American military–industrial complex, though they discounted the possibility of an event such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks.46 Yet the Middle East academics did anticipate that large-scale American military involvement, whether justified or not,47 might bring about a host of unanticipated consequences—an anticipation that was sufficiently justified by events such as the rise of ISIS, the Middle Eastern refugee crisis, the Israeli–Iranian proxy war in Syria, and the American retreat from Afghanistan.48 If the MESCs were blind to the dangers posed to America by Islamic fundamentalism, they should receive credit for realizing that any substantial American intervention would have unforeseen negative consequences.

Over the past thirty years, MESCs have attempted to resurrect themselves by taking an oppositional approach to American foreign policy in the Middle East. In the 1990s, Arab states again began to offer significant foreign funding to American MESCs, even establishing entire centers in some cases (e.g., the Saudi-funded King Fahd Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Arkansas). This foreign funding continued to flow in abundance throughout the 2000s.49 It is, thus, unsurprising that the scholars at MESCs continued to oppose American intervention in the region, as such a stance aligns with the interests of the countries that fund them.

In the years following 9/11, the federal government once again became interested in supporting MESCs, this time as part of its broader effort to combat terrorism. But many of the scholars at the centers were less interested in military development than they were in increasing Americans’ understanding of Muslims—or perhaps more accurately, sympathy for Muslims and Muslim-majority nations.

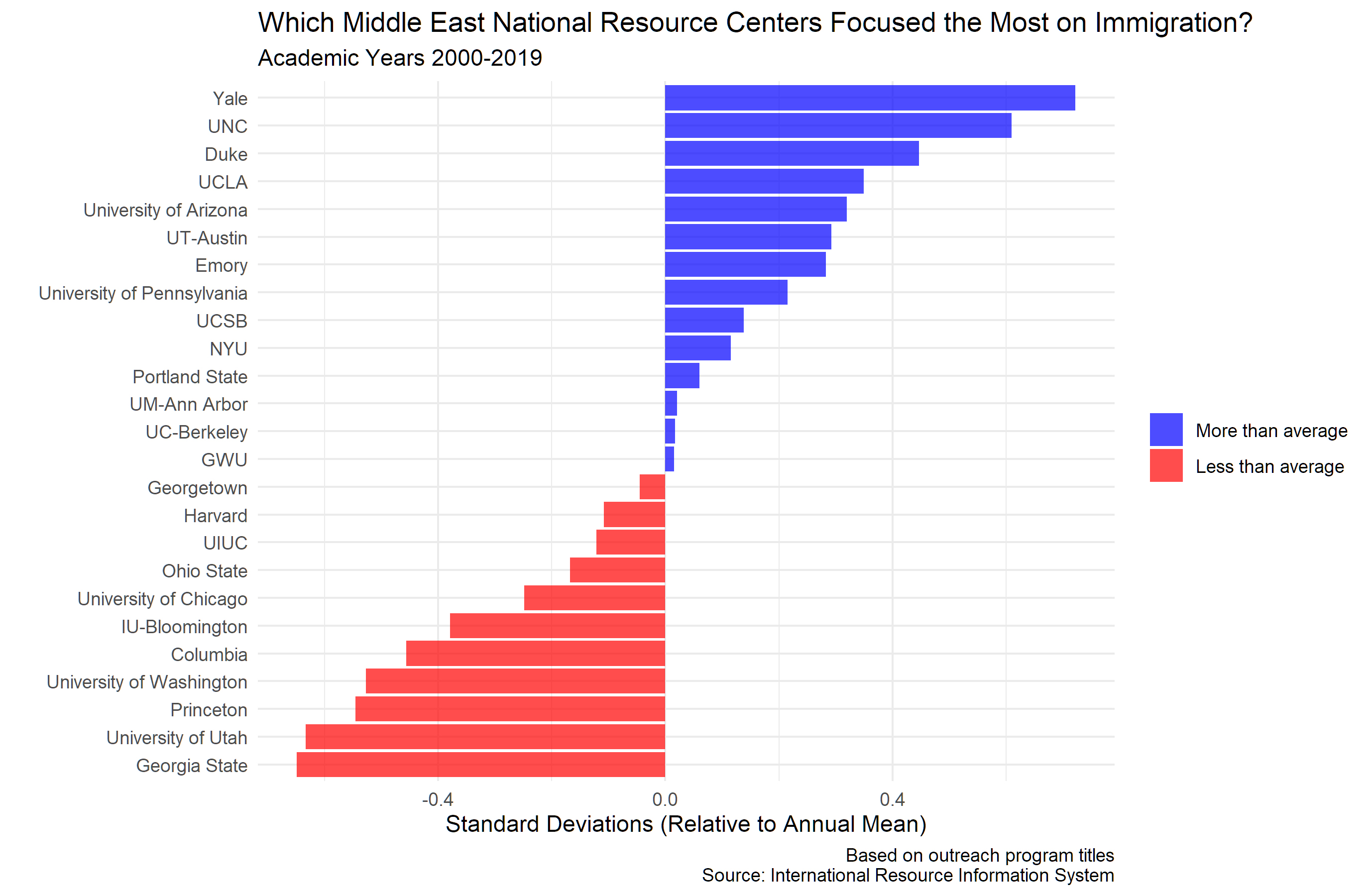

By the 2010s, the discipline of Middle East studies substantially broadened its range of topics. As this report will show, MESCs now offer a plethora of courses and content about North African countries, which previously were not considered within the scope of Middle East studies. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the discipline additionally turned its attention to immigration and refugee issues, which have remained part of the standard curriculum at MESCs ever since.

Overall, the expanded scope of Middle East studies allowed centers to move away from “Euro-centric” perspectives and to highlight the experiences of those in other regions. Melinda McClimans, assistant director of the MESC at The Ohio State University, perfectly captures this new emphasis:

When I talk to classes, I say, “Before we start talking about the Middle East, let’s just ask Middle of where? East of where?” And just, you know, recognize the Euro-centric nature of that term. But I think the other problem with that term is [that], whenever you are studying an area, you’re kind of objectifying it … I don’t know if we should still be called Middle East Studies Centers. I don’t know if we should still call it area studies or maybe just chuck that out the window and talk about something like diverse global perspectives or contexts.50

The discipline of Middle East studies has abandoned its early focus on American national security and has, instead, turned its attention to propagating “diverse” views on American foreign policy.

|

What Makes a Good MESC? The National Defense Education Act (NDEA) intended Middle East National Resource Centers to produce policy-relevant research and train students to work in the American government. Specifically, research would align with and strengthen American foreign policy initiatives. These centers would also address staffing gaps for the government by training students for key areas where America possessed few trained professionals. These two goals, however, are more properly the work of think tanks or job training programs. Neither is really a component of the true purpose of higher education—the pursuit of truth. National resource centers were created as an emergency measure during a time when America possessed little intellectual infrastructure to support its Middle Eastern policies. But emergencies should be temporary. Americans have more foreign language knowledge today than in 1958, when the NDEA was enacted into law. Technological advances such as the internet also have made a great deal of information that was previously known only to trained scholars easily accessible for the public—and for government officials who can receive sufficient information to make policy from dedicated professional training rather than a degree in Middle East Studies. Americans can debate what the government most needs from national resource centers—but they also should debate whether we still need them at all. The Cold War is long over. Higher education’s values are fundamentally different from those of MESCs, and we no longer have a compelling reason to deform America’s system of higher education to facilitate the production of government briefing papers. |

Trends in Middle East and Islamic Studies

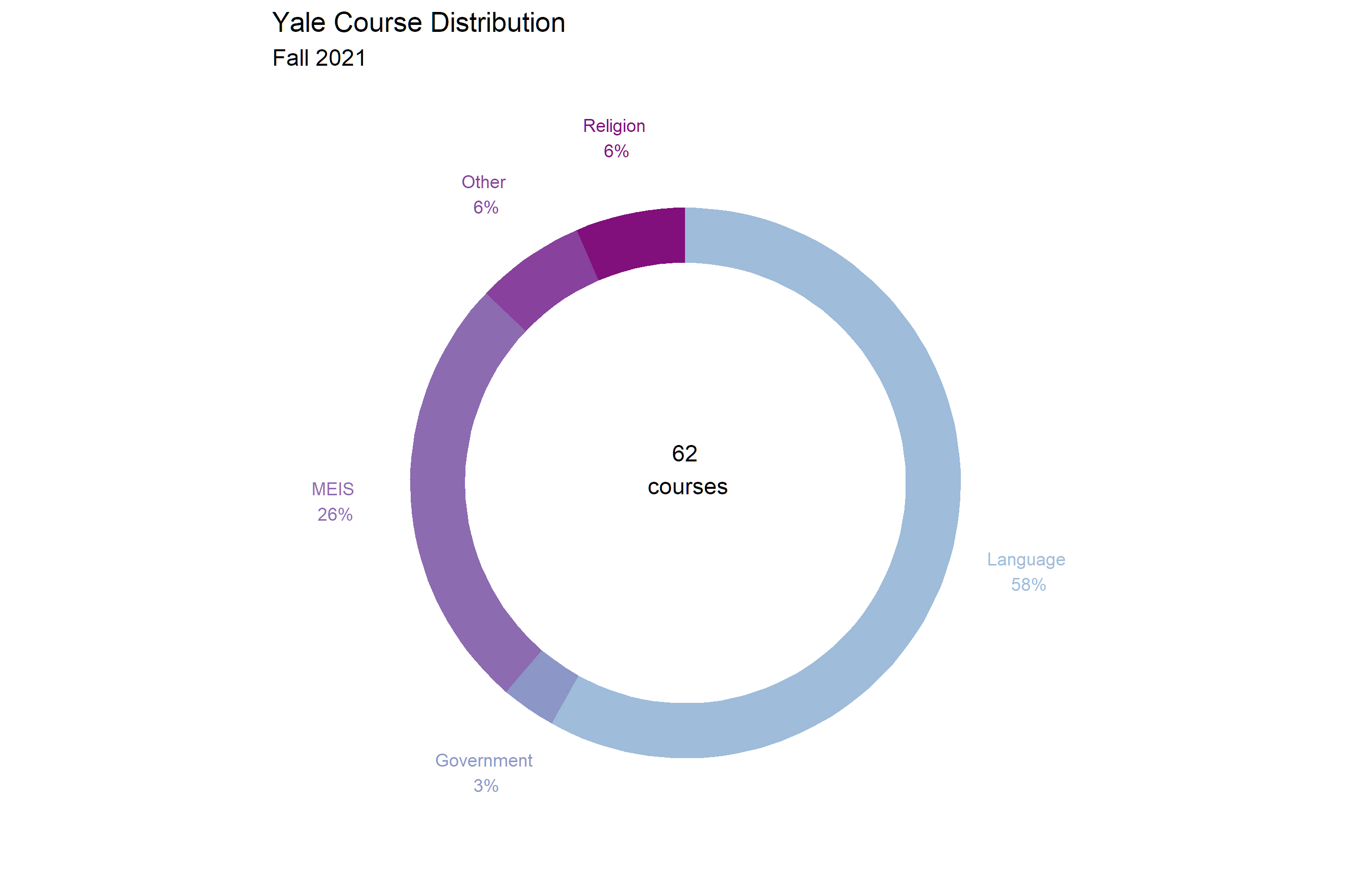

In our case studies, we provide a detailed analysis of seven American universities with Middle East or Islamic studies centers. But many more such centers exist throughout the United States. We have identified almost 50 of them, some established as recently as 2015. In this section, we use data collected from a large portion of these programs to analyze their operations and areas of focus.

Most of the programs analyzed in this section receive financial support from the Department of Education under Title VI of the Higher Education Act, which makes them National Resource Centers (NRCs). We have focused on NRCs for two primary reasons: first, because it is difficult to obtain reliable data on non-Title VI funded programs, as we can only analyze the data that is made publicly available on their websites; and second, because NRCs disproportionately influence the trajectory of MESCs throughout the United States.

Current and former NRCs include Harvard’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies (CMES), Georgetown’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies (CCAS), and the University of Chicago’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies (CMES). Other non-NRC centers typically imitate the actions of these prominent programs, albeit on a smaller scale. By studying the behavior of NRCs, we can thus increase our understanding of non-NRCs.

Practical reasons aside, we have also chosen to focus on NRCs because we believe that the standard of accountability should be higher for NRCs than non-NRCs due to the federal funding they receive. Taxpayers should be made aware of the types of research, course materials, and outreach activities that these centers produce so that they may judge whether NRCs use the funds appropriately. Privately funded or foreign-funded centers still remain a concern, as these centers must consider the interests of countries whose goals sometimes conflict with those of the United States. Nevertheless, it is startling to realize the degree to which government-funded centers engage in the types of activism and propagandization that would be expected of a center funded by a hostile foreign government.

Our analysis of the data available from academic years 2000 to 2019 reveals several major trends in MESCs:

Analysis of Title VI–Funded Programs

Title VI of the Higher Education Act authorizes funding for the ten international education and foreign language studies grant programs that currently exist. The Department of Education’s International and Foreign Language Education (IFLE) division administers these programs. They include Language Resource Centers, Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships, National Resource Centers, and several other grant programs both for institutions of higher education and for individuals interested in topics related to international education and foreign languages.

Recipient institutions must provide the Department of Education with reports on their operations and their use of federal funding. IFLE grants are contingent on compliance with regulations set forth in Title VI, and the reports are intended to ensure that these provisions are met. The Department makes the reported information publicly available through the International Resource Information System (IRIS) website to provide a measure of transparency and accountability. We used this database to obtain most of our information on Title VI–funded MESCs.51

IRIS provides information on grant titles, amounts, and recipients for each Title VI grant. The database also includes a rough breakdown of the use of Title VI funds at each NRC, such as how much was allocated to personnel expenditures or to supplies. IRIS additionally provides program-level data on outreach programs, including titles, descriptions, and intended audiences, along with similar data on funded instructional materials and course offerings.

IRIS’s data has some limitations. NRCs have existed since the 1960s, but IRIS only provides detailed data as far back as the 2000-2001 academic year. Thus, we can only draw conclusions about the behavior of these centers in the past two decades. Comparisons with the early days of the centers can only be made using limited supplemental information provided by the schools themselves. IRIS also relies on self-reported data, which subjects it to the usual caveats of reporting bias and human error. Centers may report data in slightly different formats or use different data collection methods, so comparisons between centers must take a loose rather than a precise interpretation. We believe, nevertheless, that the overall patterns and trends are accurate, and that they reflect important changes over time and differences across centers.

Figure 4: All Middle East National Resource Centers Academic Years 2000-2019

|

Columbia University |

|

Duke University |

|

Emory University |

|

Georgetown University |

|

George Washington University (GWU) |

|

Georgia State University |

|

Harvard University |

|

Indiana University Bloomington (IU-Bloomington) |

|

New York University (NYU) |

|

The Ohio State University |

|

Portland State University |

|

Princeton University |

|

University of Arizona |

|

University of California, Berkeley (UC-Berkeley) |

|

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) |

|

University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) |

|

University of Chicago |

|

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) |

|

University of Michigan-Ann Arbor (UM-Ann Arbor) |

|

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-Chapel Hill) |

|

University of Pennsylvania |

|

University of Texas at Austin (UT-Austin) |

|

University of Utah |

|

Yale University |

Middle East National Resource Centers: Basic Facts

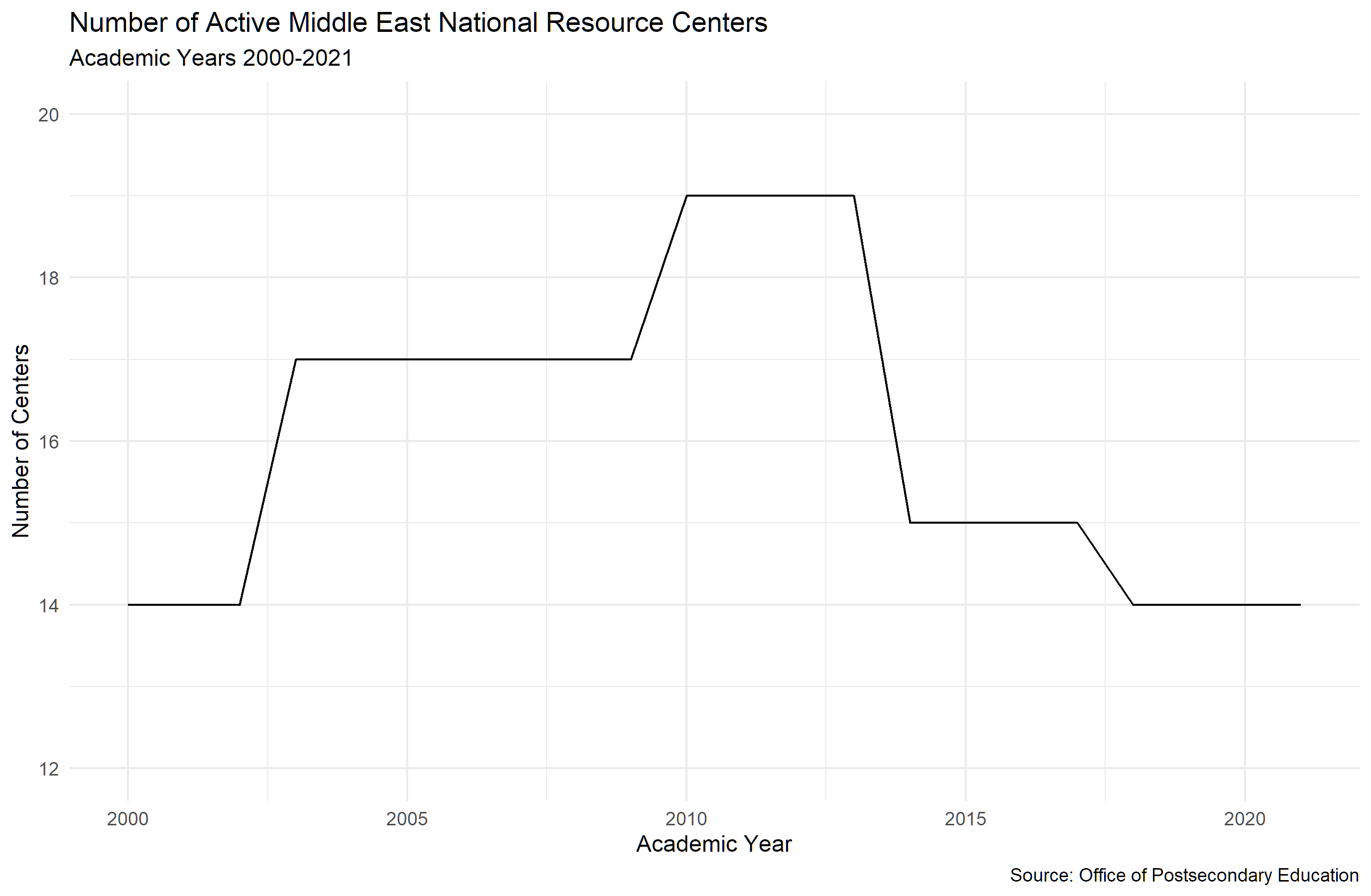

As of December 2021, fourteen National Resource Centers focus on the Middle East. The makeup of the list has changed over the years, even though the same number of Middle East NRCs existed in 2000. Several new NRCs have joined, such as the North Carolina Consortium in 2010, while others ceased to receive Title VI funding, such as Harvard’s CMES. The number of NRCs peaked at 19 and remained at that level between 2010 and 2013 before dropping again in 2014, as demonstrated by Figure 5.52

Figure 5

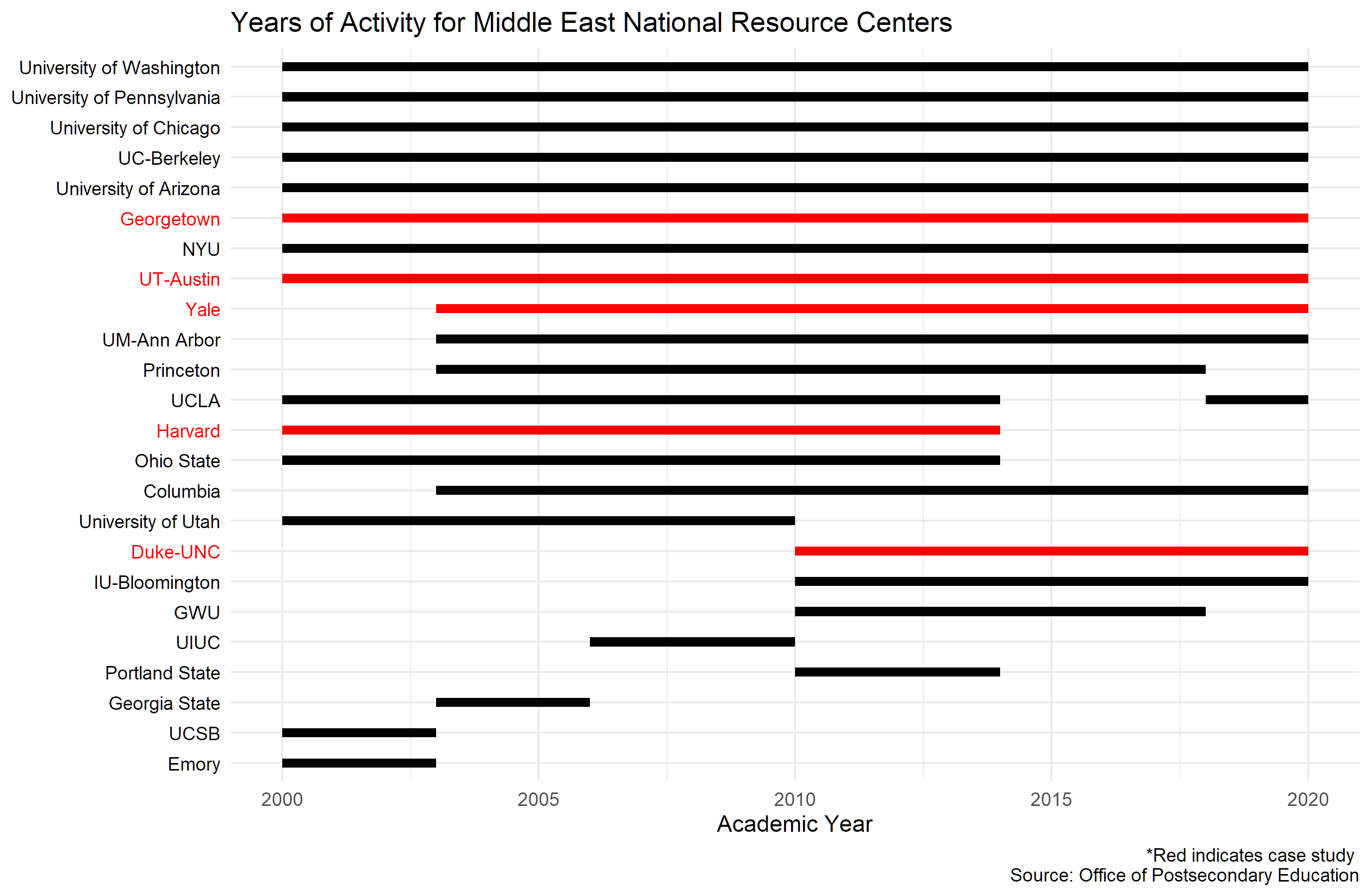

Our case studies include five of the more active NRCs during the 2000–2019 period. The selected NRCs were all active and well-established prior to 2000, apart from the North Carolina Consortium. Figure 6 shows the years of activity for all Middle East NRCs, with the ones included in our case studies highlighted in red.

Figure 6

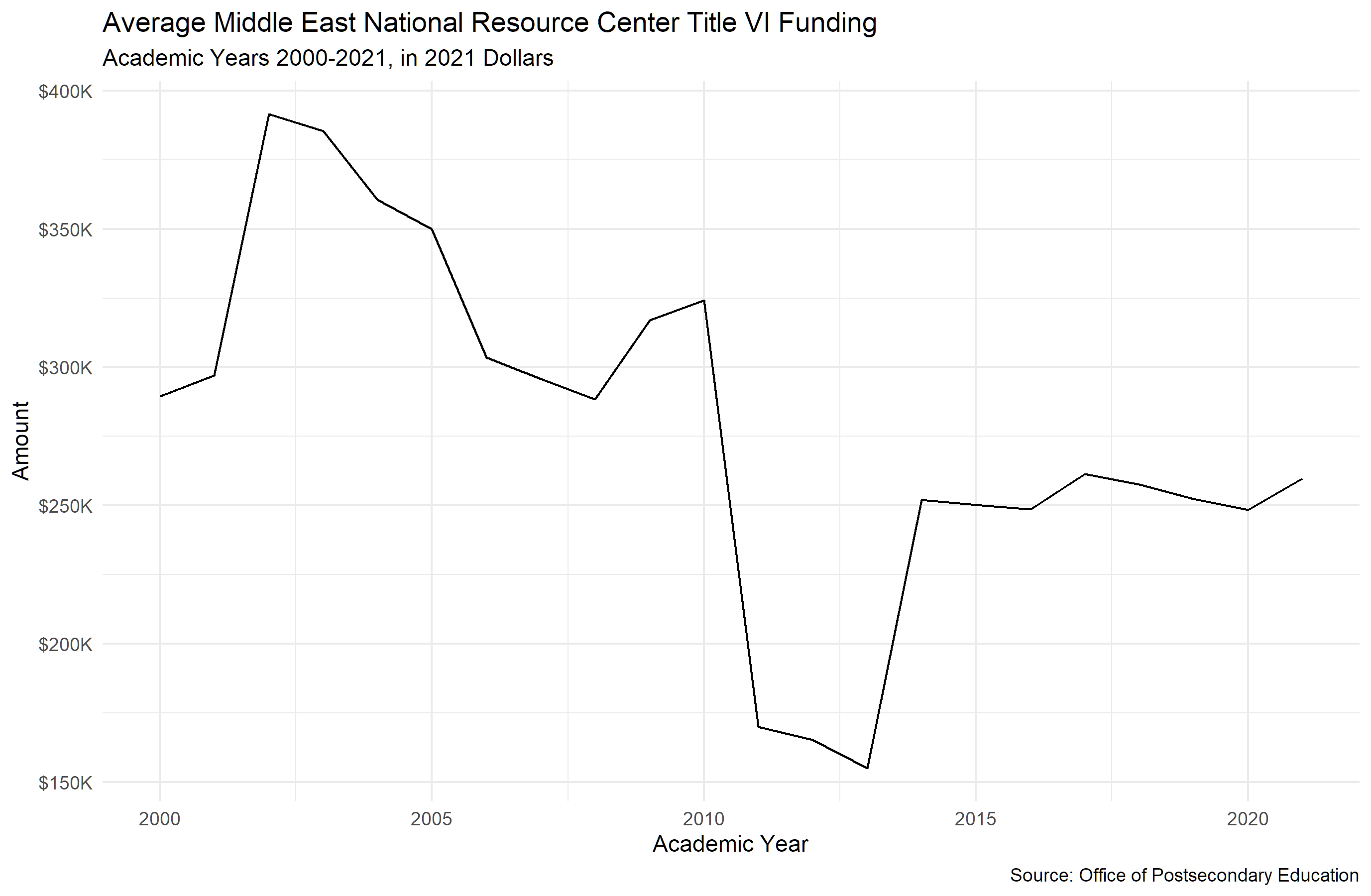

Title VI–funded Middle East NRCs receive an average grant amount of approximately $260,000 annually. Across the fourteen funded centers, this comes to a total of $3.6 million in Department of Education funding. This number, however, only accounts for the direct funding of program operations. The centers also receive government funding through research grants and fellowships for students.

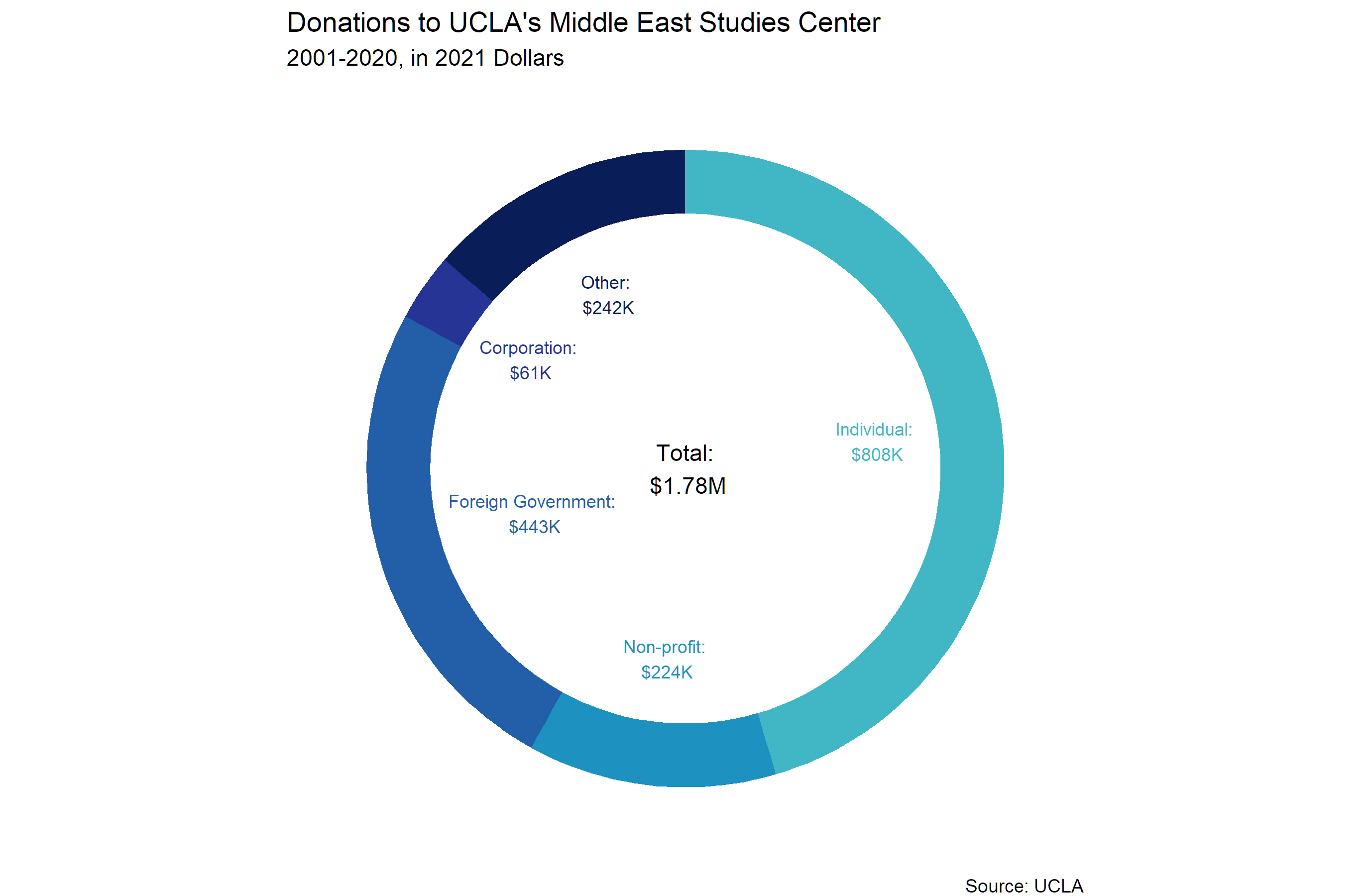

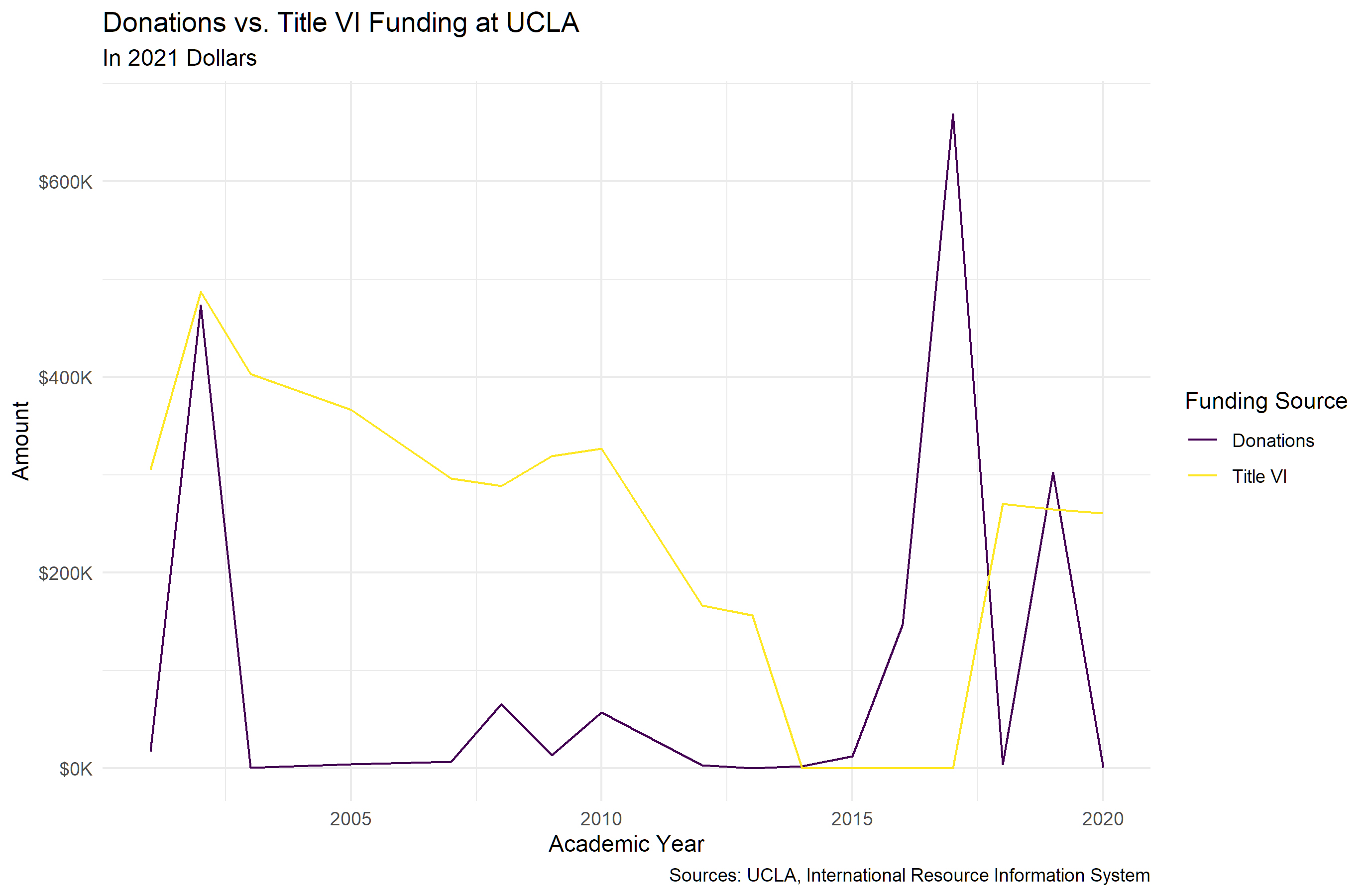

Another source of funding for these centers is direct funding from the university coffers, which may include private donations and foreign funds. This is known as “Other sources.” In our case studies, Harvard and Georgetown used some combination of foreign and private domestic funds to establish their centers. The Middle East studies departments at Duke and UNC have also accepted foreign funds in the past, but no information is available about whether the Consortium currently receives foreign funding. Thus, the distinction between American government-funded NRCs like UT-Austin’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies and foreign-funded centers such as the University of Arkansas’ King Fahd Center is not as stark as it may seem.

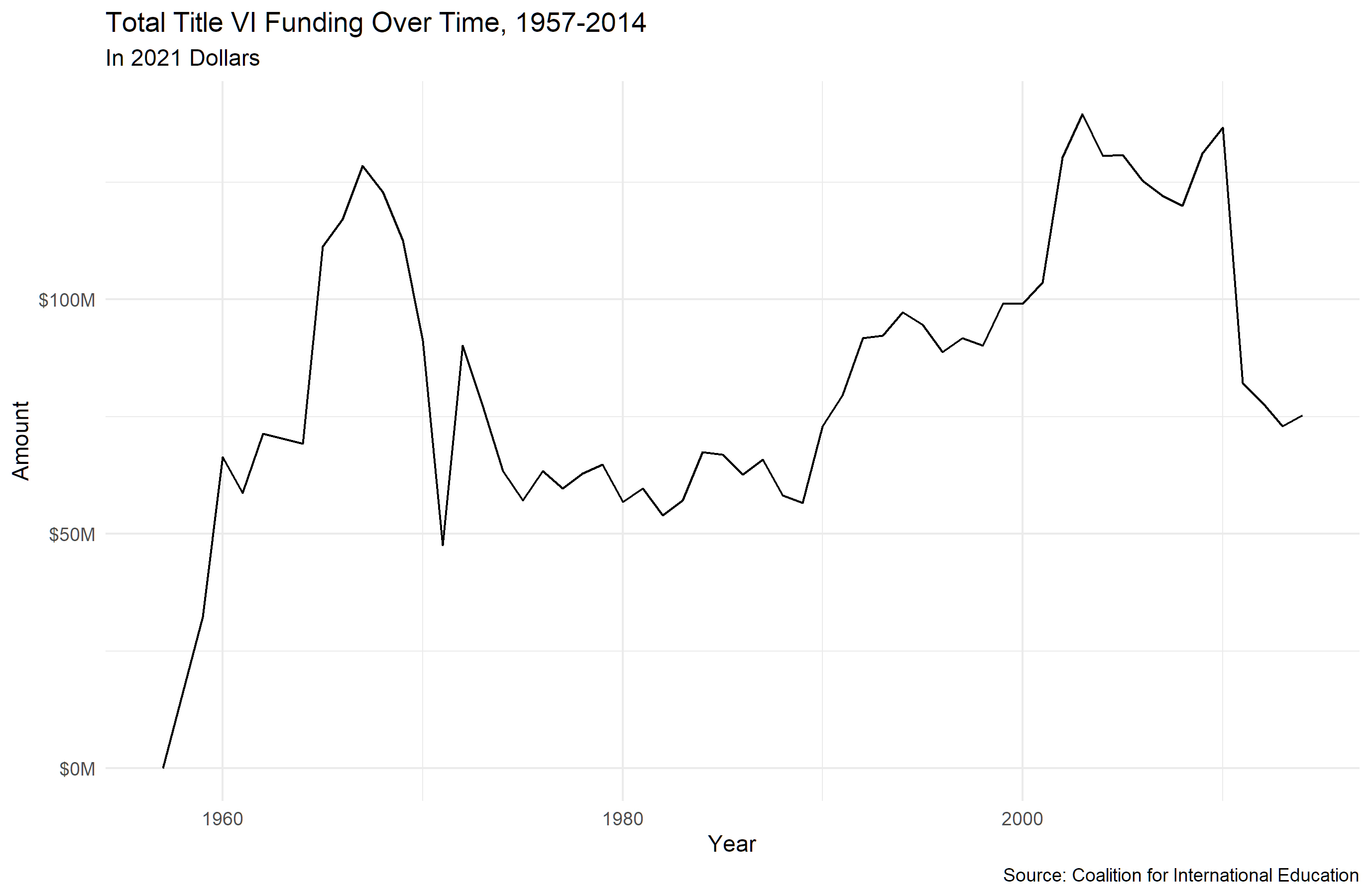

Figure 7

Figure 7 demonstrates that funding for all Title VI NRCs (not just those focused on the Middle East) has varied significantly since it began under the National Defense Education Act in 1958. The funding increased quickly after the program’s launch to a peak of $129 million (in 2021 dollars) in 1967, followed by a steep decline between 1968 and 1971. The funding level stabilized in the late 1970s and hovered around $58–70 million (2021 dollars) until the 1990s. The decrease in overall funding corresponded with a decreased interest in the NRC program, as its initial goal of training foreign language speakers had been realized and the Cold War era politics surrounding its inception had wound down. The post-9/11 Bush era, however, saw a revived interest in national security, leading the program to reach its all-time high in funding at $140 million in 2003 (2021 dollars).

The high level of funding persisted throughout the 2000s, but both overall NRC funding and Middle East–specific NRC funding dropped off steeply in 2011. Our analysis shows an almost 50% drop in Middle East–specific NRC funding between 2010 and 2011, from $6.1 million in 2010 to $3.2 million in 2011. The pattern remains the same when we account for the number of centers: in 2010, each Middle East center received an average of $320,000, while in 2011, each Middle East center received an average of $170,000.

The significant decline in funding for international education in the early 2010s can likely be attributed, at least in part, to a delayed response to the 2008 financial crash. The resulting recession led to funding decreases across the board for higher education and many other government programs, and the NRC program was no exception.

According to North Carolina Consortium director Charles Kurzman, the Obama administration’s focus on K–12 education also contributed to the decline in funding for international education, as the administration deemed the university-level programs a lower priority.53

International education leaders and proponents began to advocate for an increase in Title VI funds in the next congressional budget to reverse these trends.54 Thanks to their lobbying, support for Middle East NRCs increased from $3 million to around $3.8 million between 2013 and 2014. The increase was more pronounced at the center level, as some institutions had dropped out of the program: the average funding per center during those years increased from about $150,000 to about $250,000. Figure 8 shows that funding remained fairly stable at these levels since 2014, resting just below its level in 2000.

Figure 8

Title VI funding for NRCs has varied greatly based on the political circumstances at hand. Nearly every time the funding decreases, NRC advocates respond with apocalyptic predictions about irreversible educational deficiencies that can only be avoided by the immediate restoration of funds.

Taxpayers should be skeptical of these apocalyptic claims. The Coalition for International Education listed the many ways in which its constituents, mainly NRCs and other Title VI–funded programs, purportedly contributed to America’s national security and economic capabilities in a 2012 letter to Obama administration officials.55 The letter emphasized NRC language training capabilities and highlighted the work that NRC graduates have done in business and government.

The websites of many Middle East NRCs, however, reveal a different vision—one that attempts to separate itself from the security-oriented education that first earned these centers federal funding.

Rather than focusing on national security or economic issues, most Middle East NRCs now see themselves as builders of “cultural bridges of understanding” between the East and West who have been appointed to tear down negative stereotypes of Muslims. The stark difference between the way NRCs portray themselves to their peers and the way they portray themselves to the government reveals a fundamental disconnect between the purpose of NRC funding and the intentions of current NRC leaders.

NRC Budgets

Each NRC reports its budget to the Department of Education annually and provides a breakdown of its usage of the Title VI funds that year. The NRCs, however, are not required to submit the budgets for the centers or departments that house them, even though those budgets are often far larger than their own. The reported budgets, therefore, only show how the centers use their Title VI funding and not how they allocate their overall expenditures.

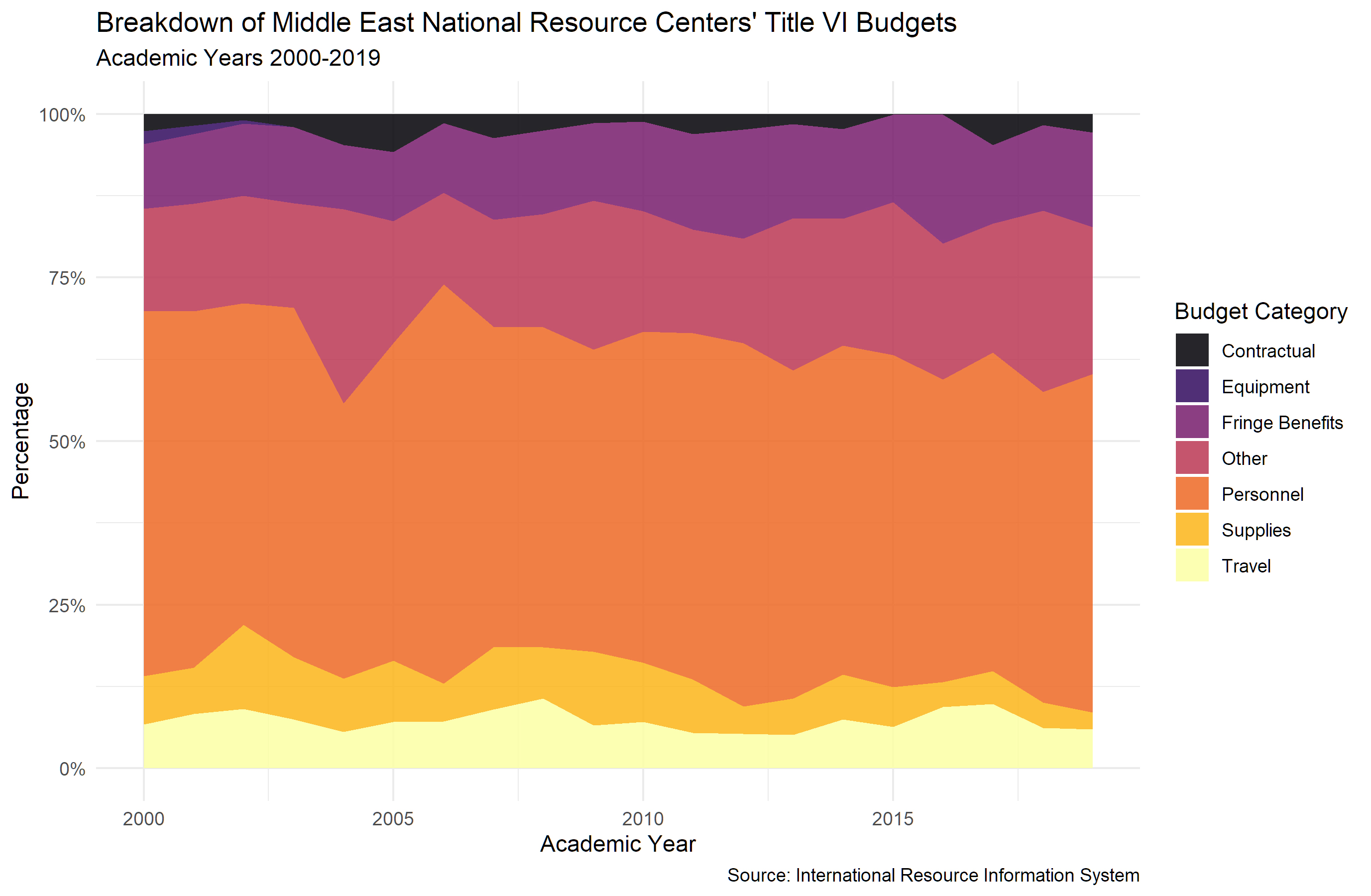

Figure 9 shows that, across all Middle East NRCs, most Title VI funding is used to pay for personnel, including both salaries and fringe benefits. These categories together amount to around 60% of the total budget each year. Personnel expenditures at NRCs mainly go toward the administrative staff who support the center’s operations, as most NRC-affiliated faculty receive their salary and benefits from appointments in other departments or named professorships.

Figure 9

Other than personnel, Title VI funds mainly go toward supplies and travel, with some small expenditures on contracts and equipment appearing intermittently. Centers also report a large, but vague, category of expenditures labeled “Other,” which typically accounts for around 20% of their budget. We can presume that expenditures labeled “Other,” along with “Supplies,” are often related to the organization of events and other programs, since centers are required to use Title VI funds to produce outreach programs and instructional material.

We can infer from the reported budgets that most NRCs use the majority of their Title VI funding to maintain a small administrative staff, with perhaps one or two employees. After this, small amounts of funding, in the low thousands, go toward the supplies for outreach materials and travel for students and faculty. Absent institutional and donor funding, the expenditure budgets paint a picture of small-scale operations in which most of the crucial employees (faculty) receive support through non-Title VI funds. The NRCs do, however, produce a substantial number of instructional materials, and they each facilitate numerous outreach programs. Both categories deserve analyses of their own.

NRC Instructional Materials

National Resource Centers produce a wide variety of instructional materials each year, both for use in their own classrooms and for the use of other educators, particularly K–12 teachers. The centers are intended to serve as resources on the Middle East for the surrounding community, and their work is supposed to increase knowledge about the region among both younger students and college-aged students. Thus, by analyzing these instructional materials, we can determine whether centers are using their Title VI funding in a way that fulfills the statutory purpose of the program.

Since 2000, Middle East NRCs have produced over 2,500 instructional materials, with an average of around 130 new materials across all NRCs per year. These materials range from curricula for undergraduate courses to podcasts and videos for the public.

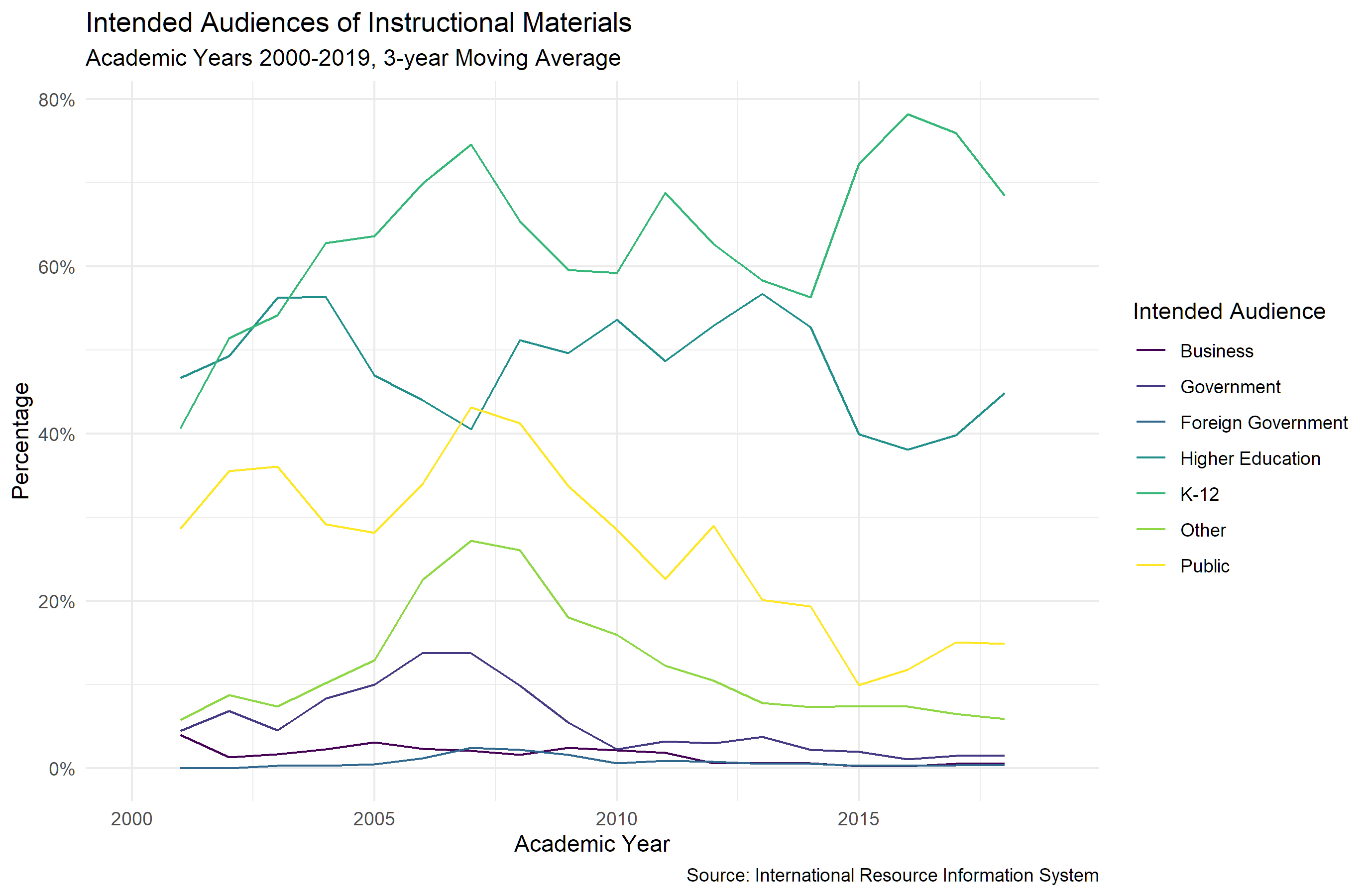

Figure 10 captures the distribution of intended audiences for these materials over time. The instructional materials produced by Middle East NRCs generally cater to K–12 audiences, a focus that has only increased over the past two decades. In recent years, over 70% of the instructional materials have targeted K–12 educators, while the percentage of materials intended for use in higher education settings has dipped below 40%.

Figure 10

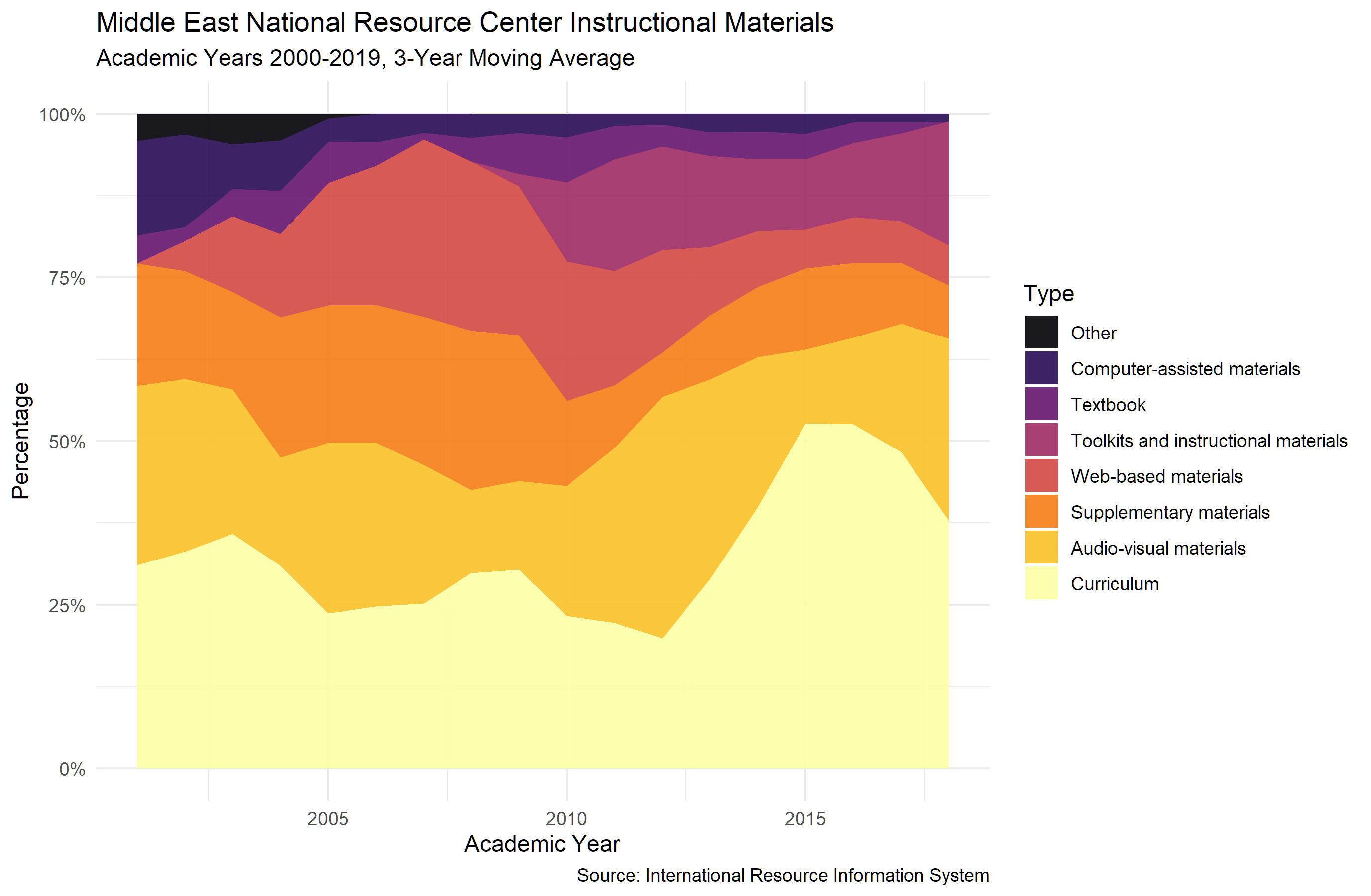

The type of materials produced by Middle East NRCs has also changed over time, as demonstrated by Figure 11. Curricula have consistently accounted for a plurality of the instructional materials produced, but in recent years, they have almost reached a majority. A new category, “Toolkits and instructional materials,” emerged around 2008 and has constituted a large portion of the instructional materials produced since then. Toolkits generally consist of physical or digital resources used for lesson plans, and they often overlap significantly with the resources in the curricula category.

Figure 11

The curricula and toolkits produced by Middle East NRCs mostly target K–12 education, with over 60% of curricula and 70% of toolkits designed for use in elementary and secondary education settings. Many of these materials aim to increase cultural literacy and “globalize the classroom” by exposing children to different cultures and “decentering” the European, Western, and American cultural experiences.

The instructional materials produced by Middle East NRCs often aggressively push a very specific political agenda to accomplish these aims. Consider, for example, a 2017 toolkit produced by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill titled, “‘Women and Gender in the Middle East’ Reading Guide.” The toolkit consists of a set of readings and questions that directs students to resources such as a video on Edward Said’s Orientalism posted by the YouTube channel “Invictapalestina,” speeches from a conference on “pan-Arab feminism,” and an anthology of Arab feminist writing. This list of resources hardly provides a balanced perspective on women’s social issues in the region.56

Other materials encourage the use of controversial educational approaches, such as critical pedagogy, and push harmful ideologies in the classroom, including critical race theory. For example, UT-Austin’s CMES has participated for at least three years in a workshop for K–12 teachers called the “Critical Literacy for Global Citizens Summer Institute.” The university’s Hemispheres Consortium sponsored the event, which is made up of the various Title VI–funded area studies centers at the university. On its website, Hemispheres states that it provides educational resources about “diverse world regions” to educators “under the aegis of [its] Title VI mission.”57

UT-Austin claimed in its 2018 report to the Department of Education that the critical literacy workshop supported “instructional goals for literacy standards for the State of Texas” by “explor[ing] the use of critical literacies and international children’s literature.” Yet so-called “critical literacy” has very little to do with actual literacy. Critical literacy, an approach that falls under the broader umbrella of critical pedagogy, encourages children to find embedded power structures within the texts they read. Children are then taught to relate these power structures to ideas of equity and social justice. Rather than teaching students the basic skills required for reading comprehension, critical literacy trains students to espouse the tenets of critical theory.58

A perusal of the Summer Institute at UT-Austin reveals further evidence of the political agenda behind the program. The webpage for the June 2021 event included the following session topics:59

Although the Hemispheres Consortium claims to have a “Title VI mission,” the material presented at its annual Summer Institute clearly does not promote language acquisition or national security. In 2019, UT-Austin’s CMES contributed ten instructional materials to the Summer Institute, including materials on “Kindergarten Global Citizenship,” “Understanding & Enacting Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy,” and “Starting and Sustaining Critical Race Literacy in the Classroom.”

The ideological bias in Title VI–funded events and materials highlights the need for greater oversight of recipients of government funding, as well as a broader re-evaluation of the state and federal programs that provide support to these centers.

NRC Outreach

In addition to creating instructional materials, NRCs also organize outreach programs for their local communities, which primarily consist of events that engage scholars and the public on topics related to a specific region. All NRCs must report a list of their outreach programs annually to the Department of Education, along with the intended audience for each program and a brief description of its content. Middle East NRCs must justify the utility of their outreach efforts in their annual report and explain how their programs further the public’s education about the region to continue to receive outreach funds.

From 2000 to 2019, NRCs at twenty-five colleges conducted over 22,000 outreach programs. While the average is around 1,100 outreach programs per year, the actual number of programs conducted each year varied significantly, with an early peak in 2005 at just over 1,600. The peak came during a year in which funding for NRCs was quite high, and the number of programs was greater than in previous (and subsequent) years.

Outreach activity also varies significantly across NRCs. Yale’s CMES tops the list with almost 120 outreach programs per year, whereas Georgetown’s CCAS holds fewer than thirty. The variation cannot be attributed to differences in funding: a simple correlation test between the yearly funding levels and the number of outreach programs across NRCs does not yield a statistically significant correlation. The lack of a correlation suggests that the centers decide for themselves how many outreach programs to hold per year rather than deciding based on funding constraints or a mandate from the Department of Education.

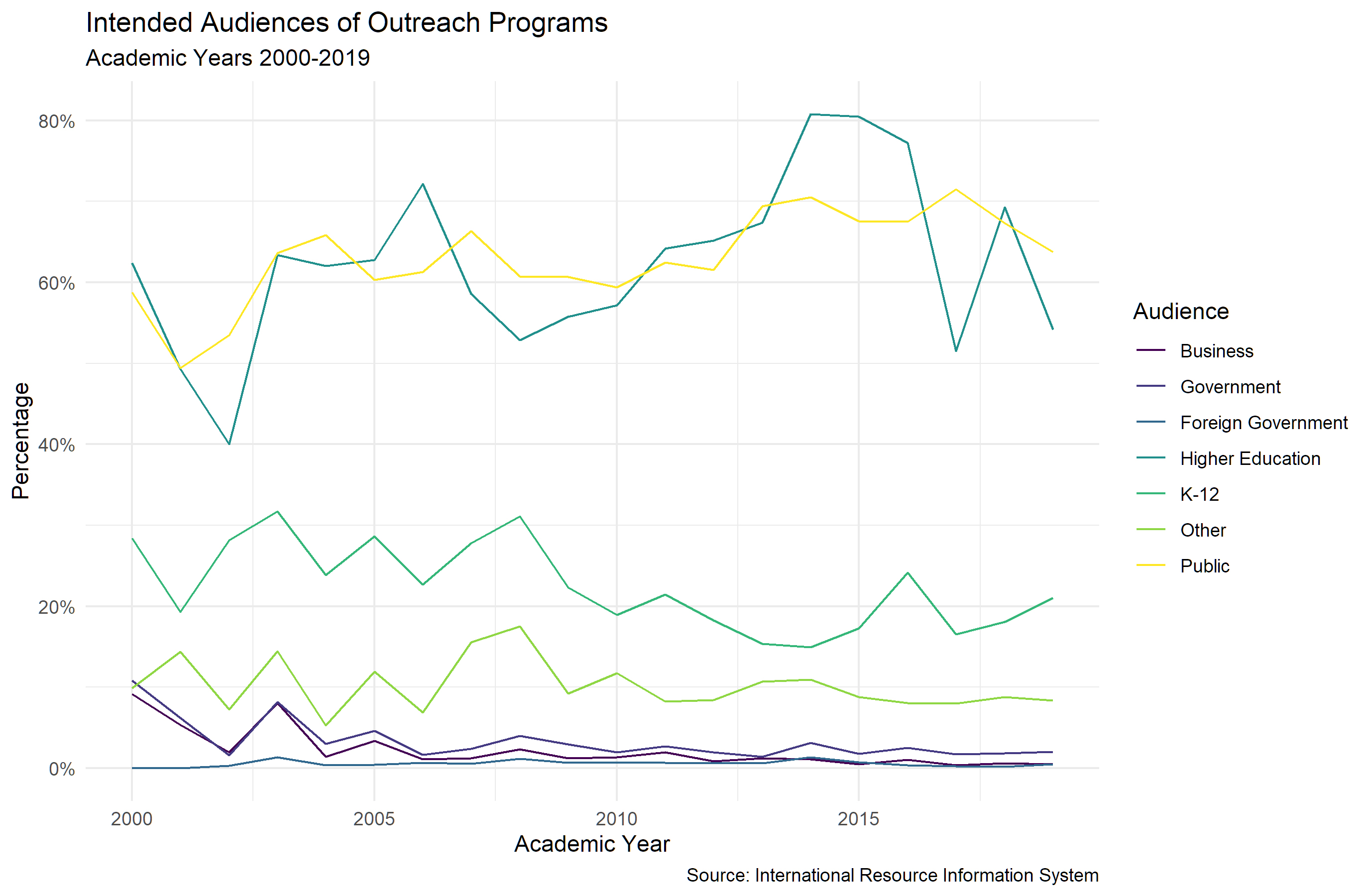

Figure 12

Figure 12 shows that many outreach programs at Middle East NRCs, around 60%, target higher education or the public; this holds true for all years studied. Outreach programs for these audiences primarily consist of lectures from resident or visiting scholars, discussions of books and films, and faculty workshops.

Elementary and secondary school educators are the next most common audience. The scholars at Middle East NRCs typically do not interact with K–12 students directly; instead, the centers hold K–12 teacher workshops in which they discuss curricula and lesson plans that the teachers can implement in their classrooms. These programs help to expose younger students to different cultures and encourage them to study foreign languages. But they also promote certain political and social agendas, as observed in our case studies.

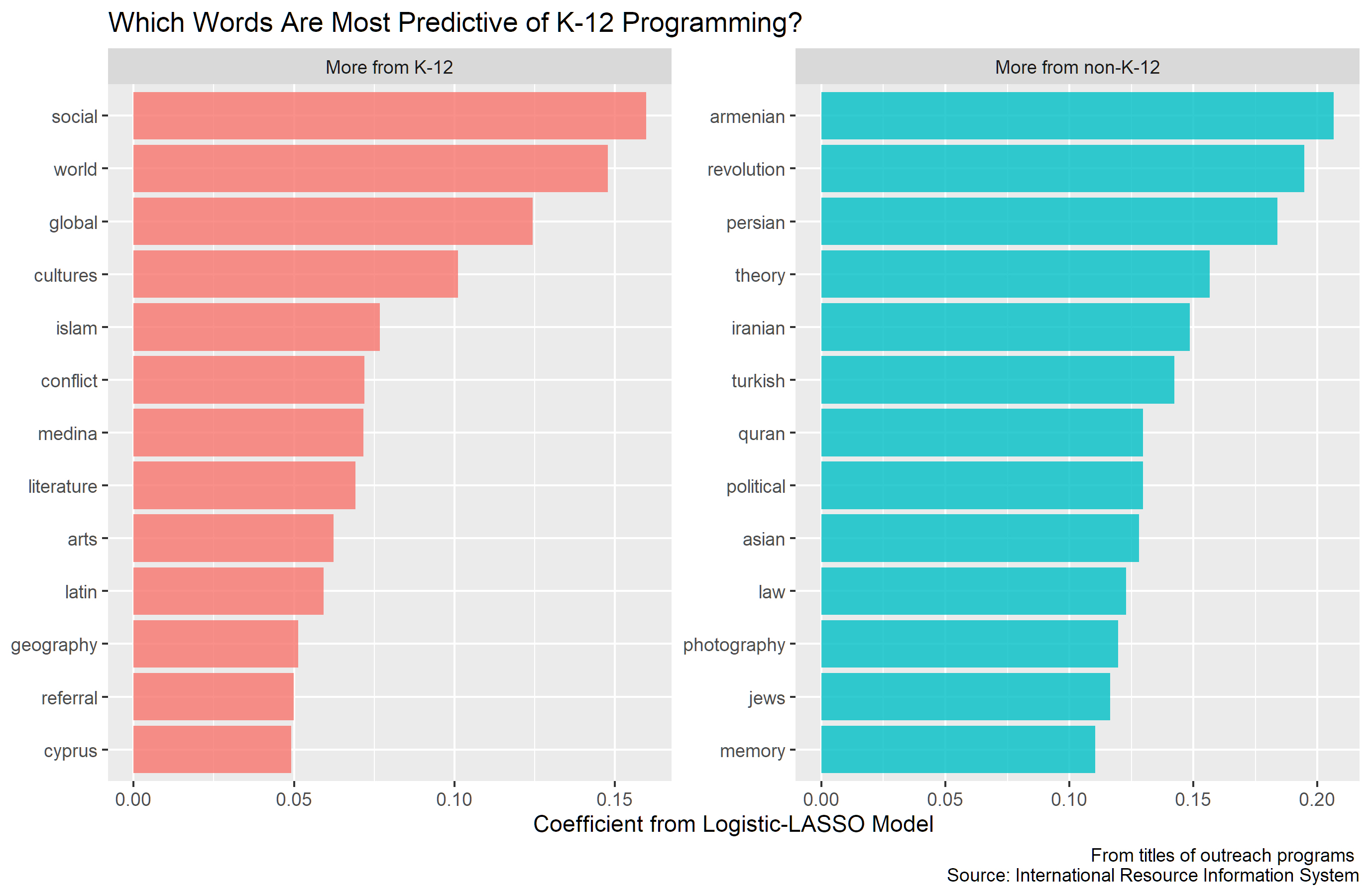

Figure 13 shows the words that most distinguish K–12 programming from non-K–12 programming.60 Non-K–12 programming, which focuses primarily on academia, fixates on more specific topics and regions of the Middle East, as demonstrated by words such as “Persian” and “Turkish.” K–12 programming, on the other hand, focuses more on cultural literacy and understanding while placing less of an emphasis on learning specific facts about the region. The left-hand side of Figure 13 demonstrates the prominence of broad terms like “global” and “cultures” in the titles of K–12 outreach programs

Figure 13

NRCs sometimes partner with local organizations to conduct outreach activities, and they often tailor these programs to a specific audience that is of interest to the local partner. Duke Divinity School’s Muslim Chaplain, for example, organized a program in 2004 that “provided training to 80+ health care providers on culturally sensitive health care delivery to Muslims.”

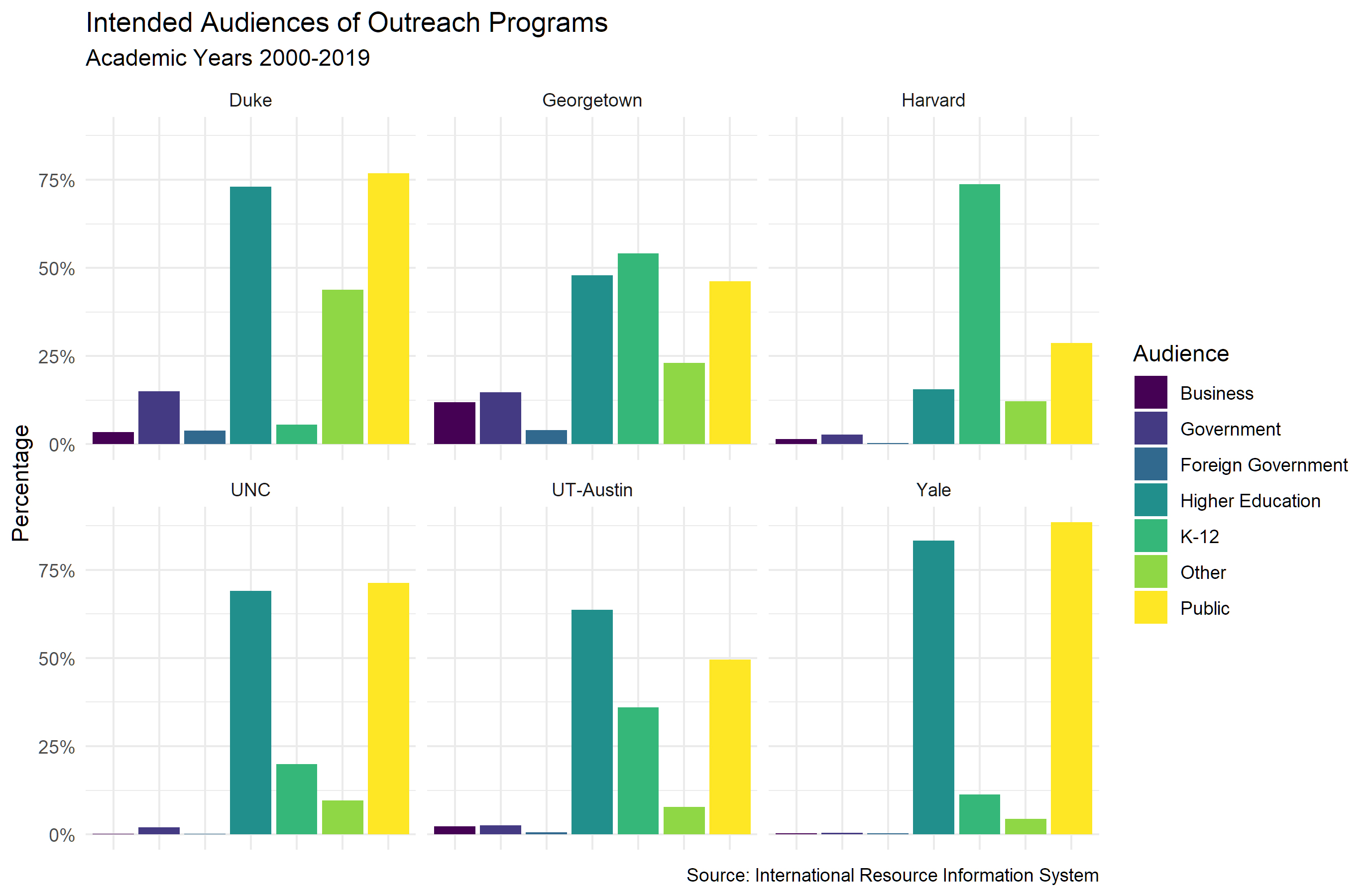

Figure 14 shows the distribution of outreach programs by audience type at each of the Middle East NRCs from our case studies. Our analysis includes seven types of audiences: business, government, foreign government, higher education, K–12, the public, and “other,” which consists of miscellaneous groups such as health or policy professionals, ethnic communities, and libraries.

Figure 14

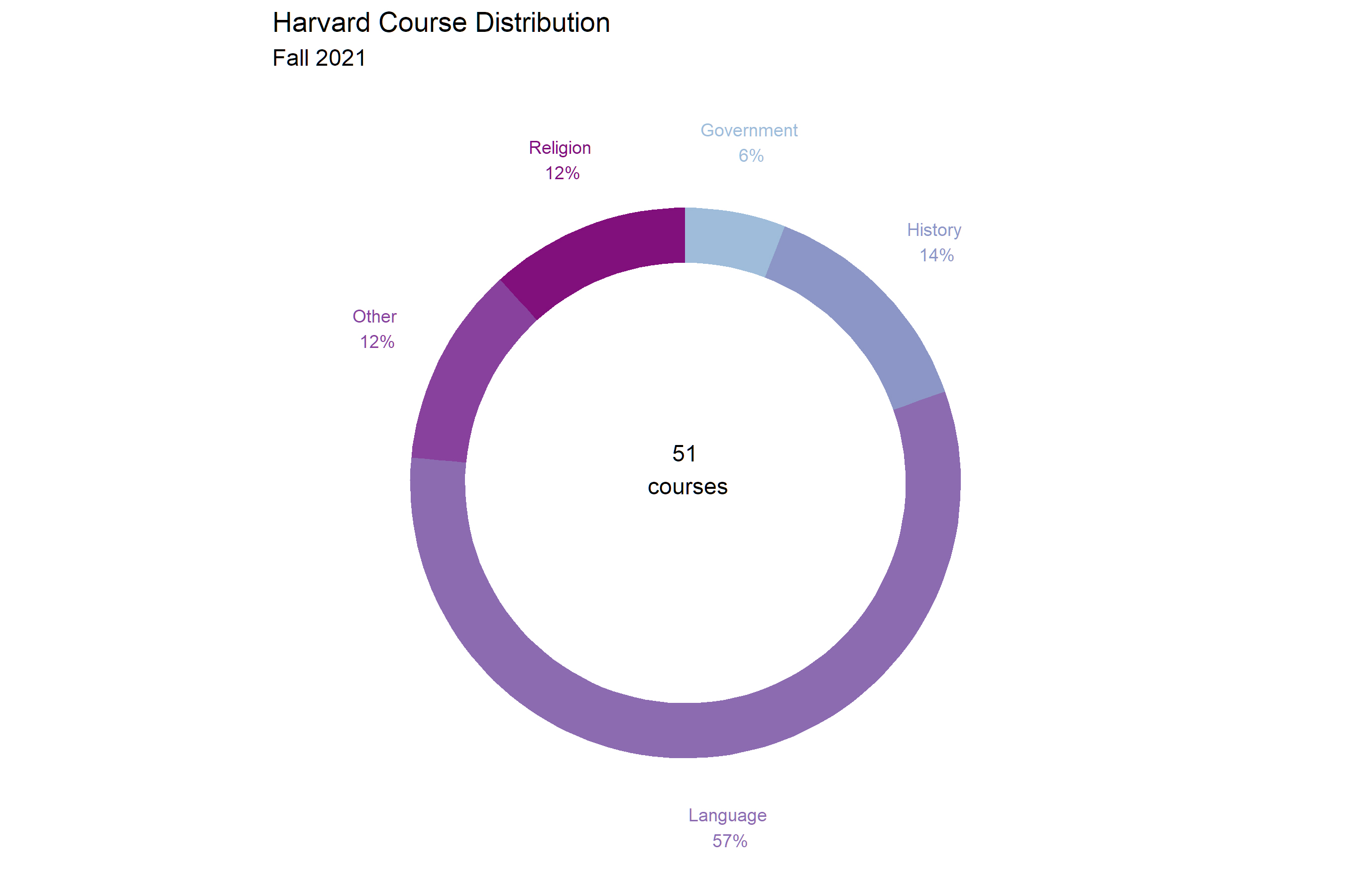

Harvard, which has conducted outreach programs since the 1970s, focuses primarily on K–12 outreach. Yale, meanwhile, offers more academically oriented outreach programs that cater to higher education audiences. Georgetown, given its location in Washington, D.C., organizes significantly more programs intended for government officials than other NRCs.

Across all our case studies, only a small number of outreach programs cater to the interests of business leaders and government officials. Programs designed for these audiences tend to focus more on practical issues. For example, an outreach program for businessmen could discuss how American businesses can better understand and work with the Islamic financial and monetary systems. The practical bent of the business world may explain why Middle East NRCs focus more of their outreach on other audiences. In general, K–12 educators and academics seem to be more receptive to the bread-and-butter of MESCs: cultural literacy workshops and other diversity-oriented training.

Outreach Topics

NRC outreach programs tend to be very responsive to contemporaneous political events. An analysis of the coverage of specific topics by NRC outreach programs over time shows that their content rapidly changes to “keep up with the times.” NRCs dramatically shift their coverage of politically charged topics as public interest in the issues waxes and wanes.

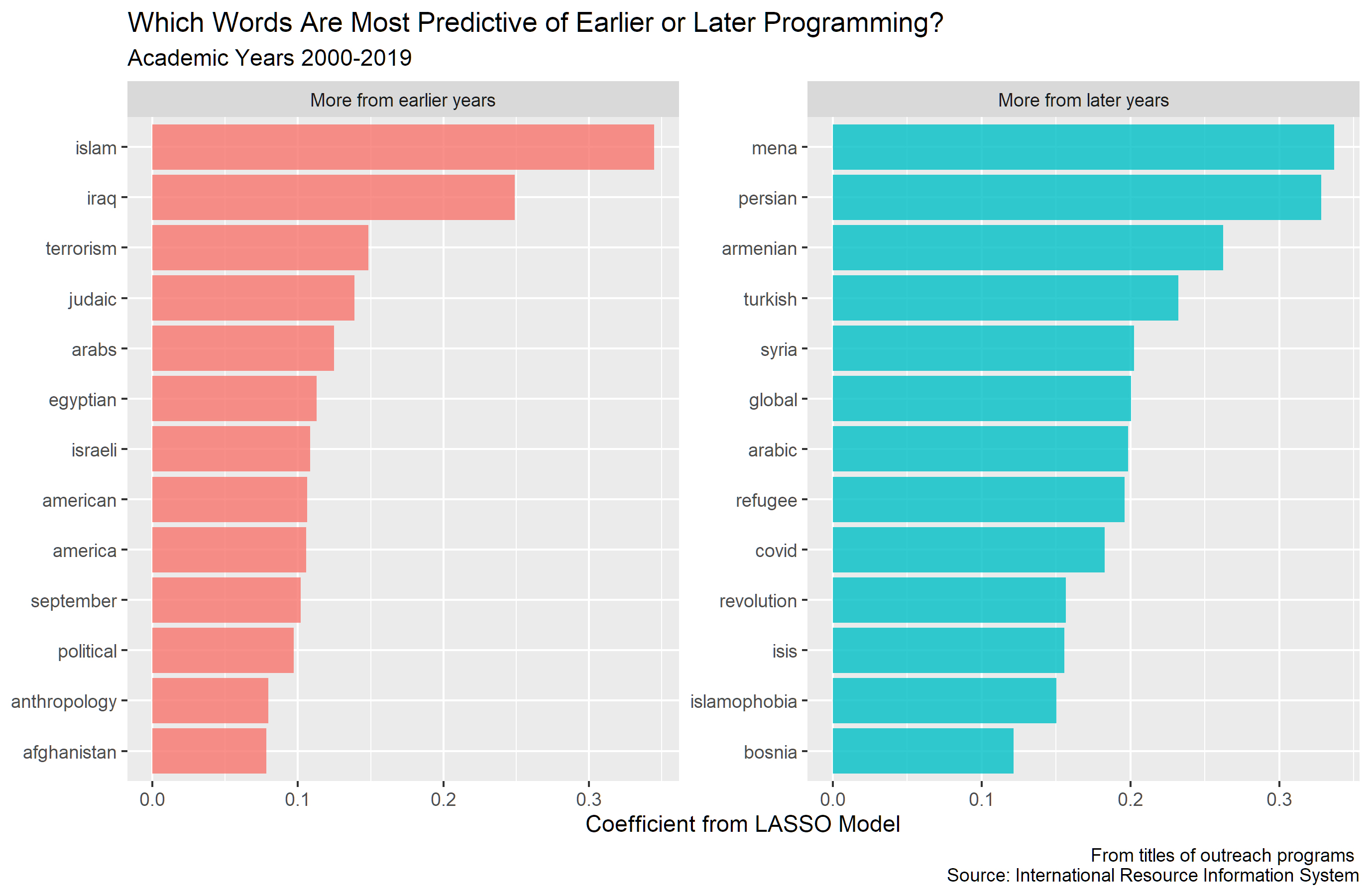

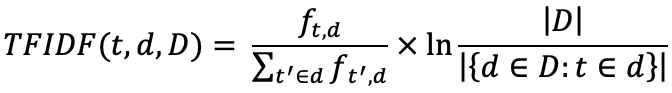

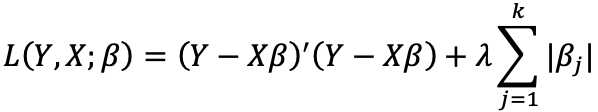

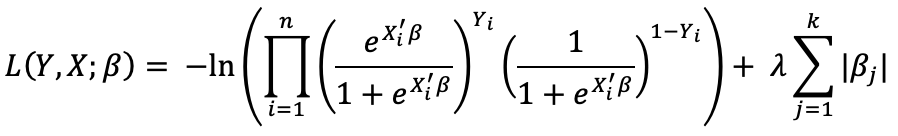

Figure 15

Figure 15 shows the results of a LASSO regression model in which the presence of a word in an outreach program title is used to predict the year in which that program took place. The words with the largest negative coefficients, which predict an earlier year, and the largest positive coefficients, which predict a later year, are shown on the left- and right-hand sides of the chart, respectively. The model excludes words with no topical content, such as “speaker,” “program,” or “Saturday,” to improve the interpretability of the results.

An analysis of the earlier years shows a distinct focus on terrorism, Iraq and Afghanistan, and other topics related to the conflicts and events of the early 2000s. Frustrated by an aggressive American foreign policy agenda in the Middle East, many academics focused significant time and attention on the deconstruction of Muslim stereotypes. They also advocated against the War on Terror. The interests of academics during that time were reflected in the outreach programs sponsored by MESCs, which focused more on American foreign policy and the aftermath of 9/11.

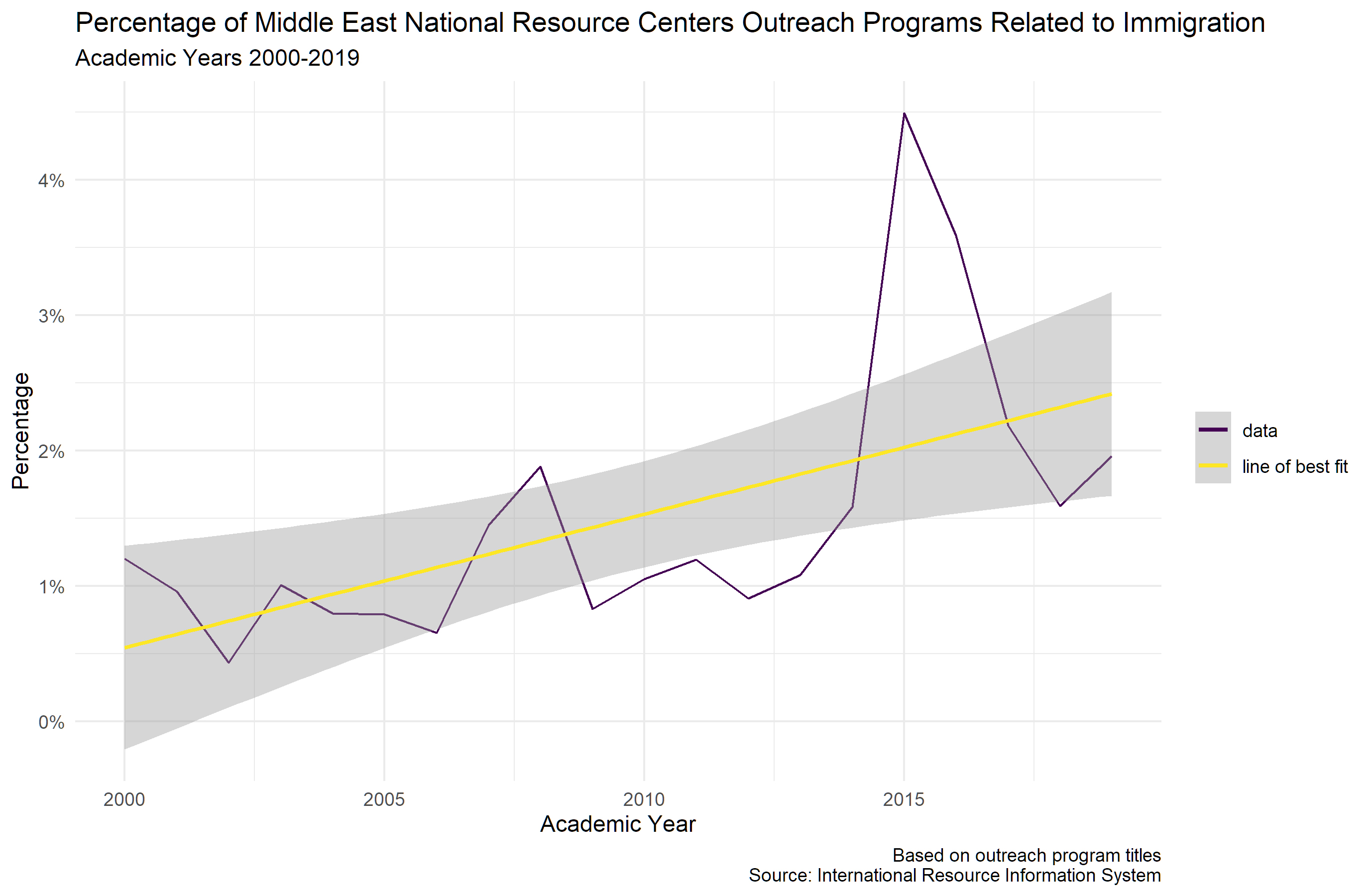

In later years, centers responded to the events of the 2010s and 2020s and shifted their programming accordingly. For example, “Covid” was one of the most predictive words for later programming. The term “mena,” or more properly “MENA,” also appears as an important predictive word of newer programs. The prevalence of the term, a neologism for “Middle East and North Africa,” reflects a growing interest among academics to expand the geographic scope of MESCs to include North African countries such as Algeria and Morocco. These countries do have religious and cultural ties to the Middle East, but they have not historically been considered within the formal scope of Middle East studies.

We also see the introduction of political and social issues such as refugees and Islamophobia in later programs. The shift in focus corresponds with the massive increase in Muslim migration, particularly in Europe, during the 2010s. MESCs generally responded to the waves of refugees and migrants by promoting the integration of Muslims into Western countries. Many academics characterized concerns about this migration from more conservative political figures as “Islamophobic.”

The remainder of this section analyzes the prevalence of specific topics across all of the outreach programs studied. These topics were chosen based on their connection to important social issues related to the Middle East or to America. We created a “dictionary” of terms related to each topic to capture the full scope of the topic’s prevalence across the outreach programs. Each dictionary contains a list of words that are associated with the topic at hand.61

We provide the dictionary for “terrorism” as an example below:

|

terrorism |

|

terror |

|

terrorist |

|

terrorists |

|

counterterrorism |

|

jihad |

|

jihadism |

|

jihadi |

|

jihadis |

|

jihadist |

|

bomb |

|

bombing |

|

bombings |

|

hijack |

|

hijacking |

|

hijackings |

|

hijacker |

|

qaeda |

|

osama |

Next, we matched the dictionary terms with the words found in outreach program titles. This process was not an exact science, and the results should be taken as approximate rather than precise. The overall trends and patterns that emerge from this process, however, reflect the differences in coverage of these topics across schools and over time.

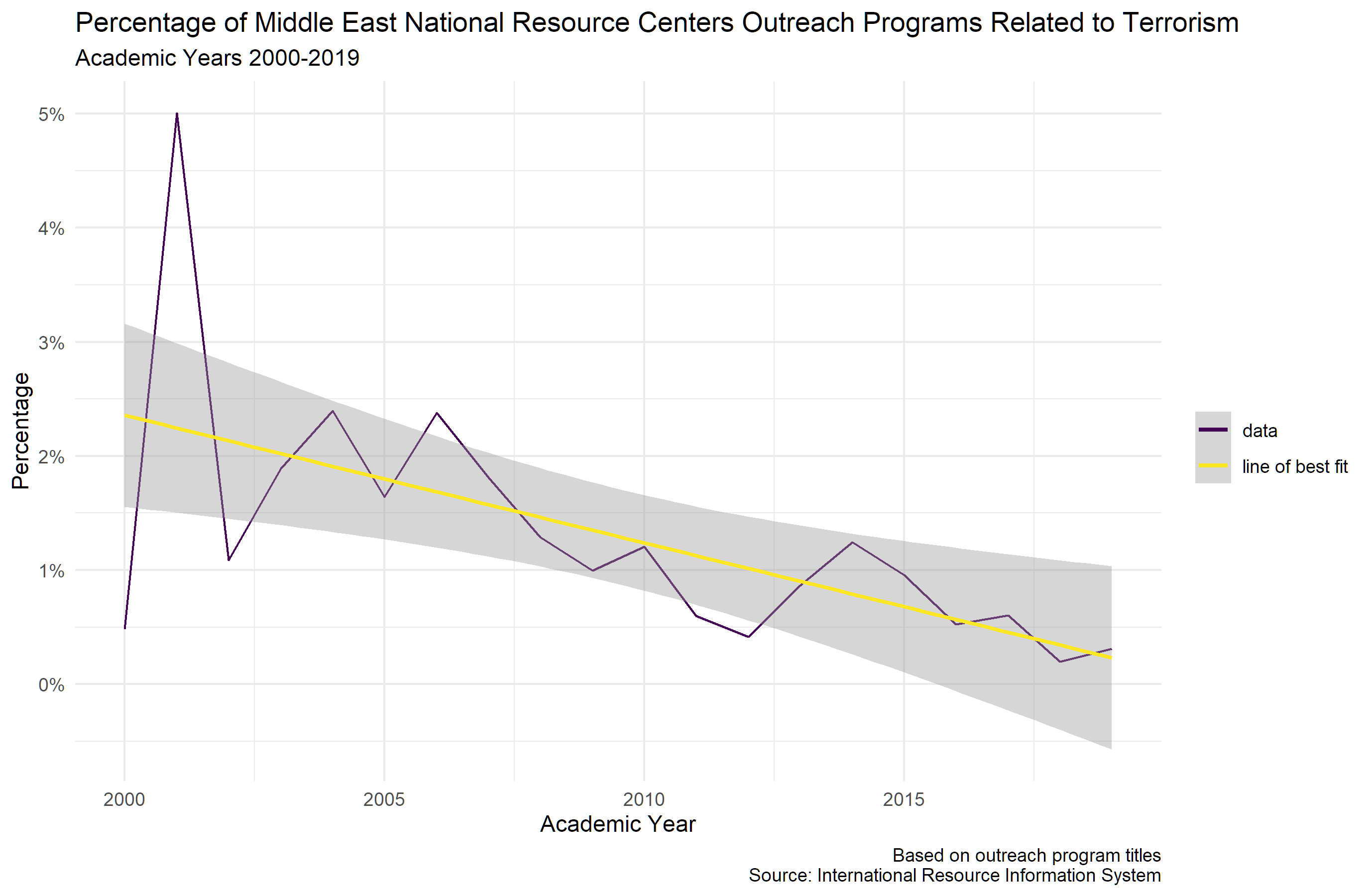

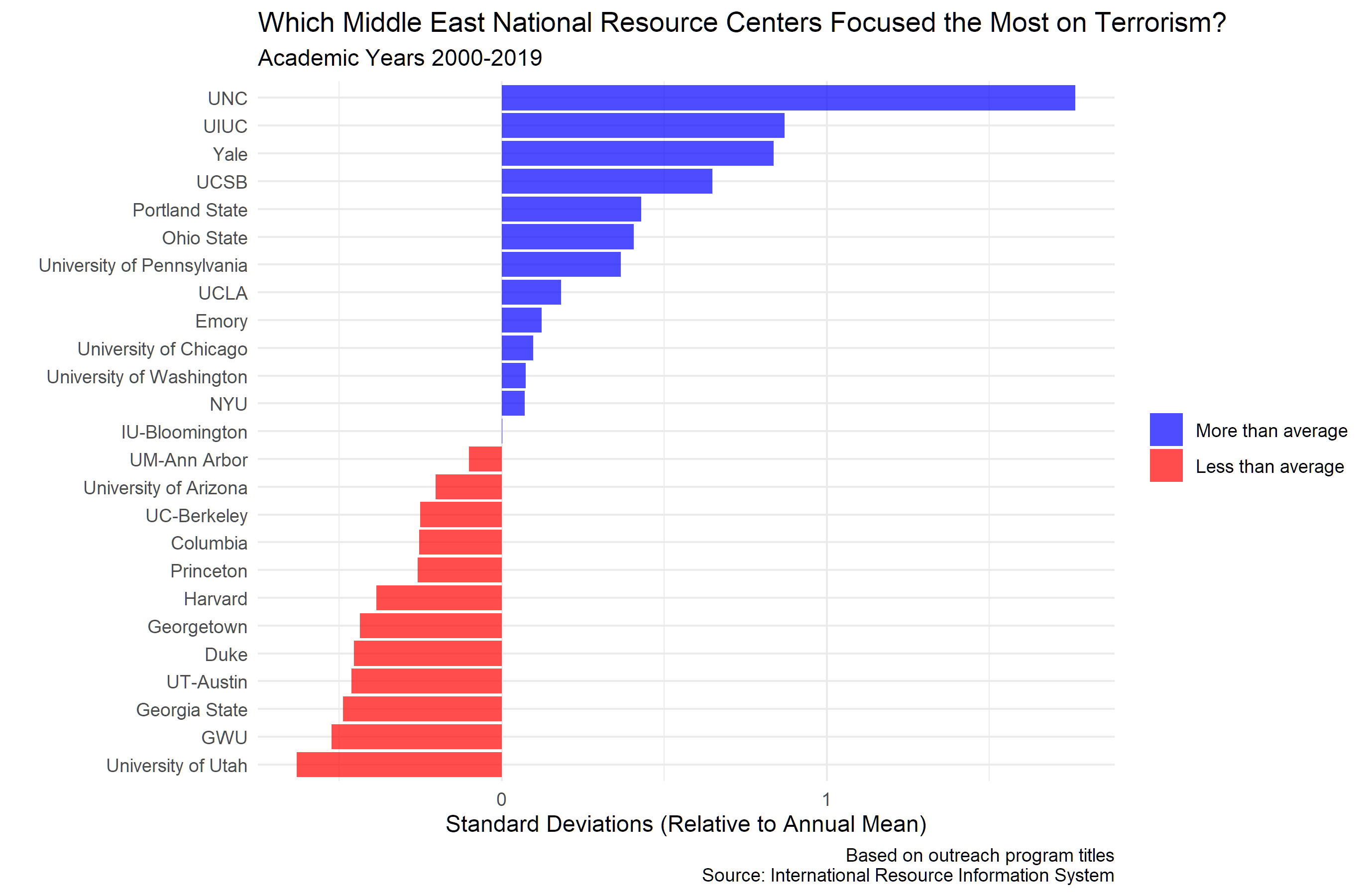

First, let us consider the topic of terrorism. This topic became closely associated with the Middle East, and more specifically with Islam, in the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks, which sparked the so-called “War on Terror” and the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Middle East scholars devoted significant time and resources to the subject, as the association of terrorism with Islam caused great controversy in the years following 9/11.

Figure 16

Figure 16 shows the prevalence of terrorism-related terms in outreach program titles from 2000 to 2019. We see a significant downward trend, with less than 0.5% of outreach programs mentioning terrorism or related terms by 2019. Unsurprisingly, coverage spiked in 2001, when 5% of outreach programs discussed terrorism, but it dropped rapidly in later years. The steep decline likely reflects a general desire among the centers to avoid the topic of terrorism, despite its importance for national security and its relevance to the Middle East. Programs and courses at MESCs often mention 9/11, but they tend to consider the attacks in the context of their effects on Muslims rather than the context of terrorism more broadly.

Some programs, nevertheless, discuss terrorism more than others. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill addressed terrorism far more often than other NRCs, as shown by Figure 17. The focus likely reflects the priorities of the center’s leadership: North Carolina Consortium director Charles Kurzman insisted in an interview that the issue of Islamic terrorism is overblown.62 UNC takes a different approach than centers such as Georgetown’s CCAS, which avoids the terrorism issue almost altogether, but its coverage of terrorism is not motivated by concern for American national security.

Figure 17

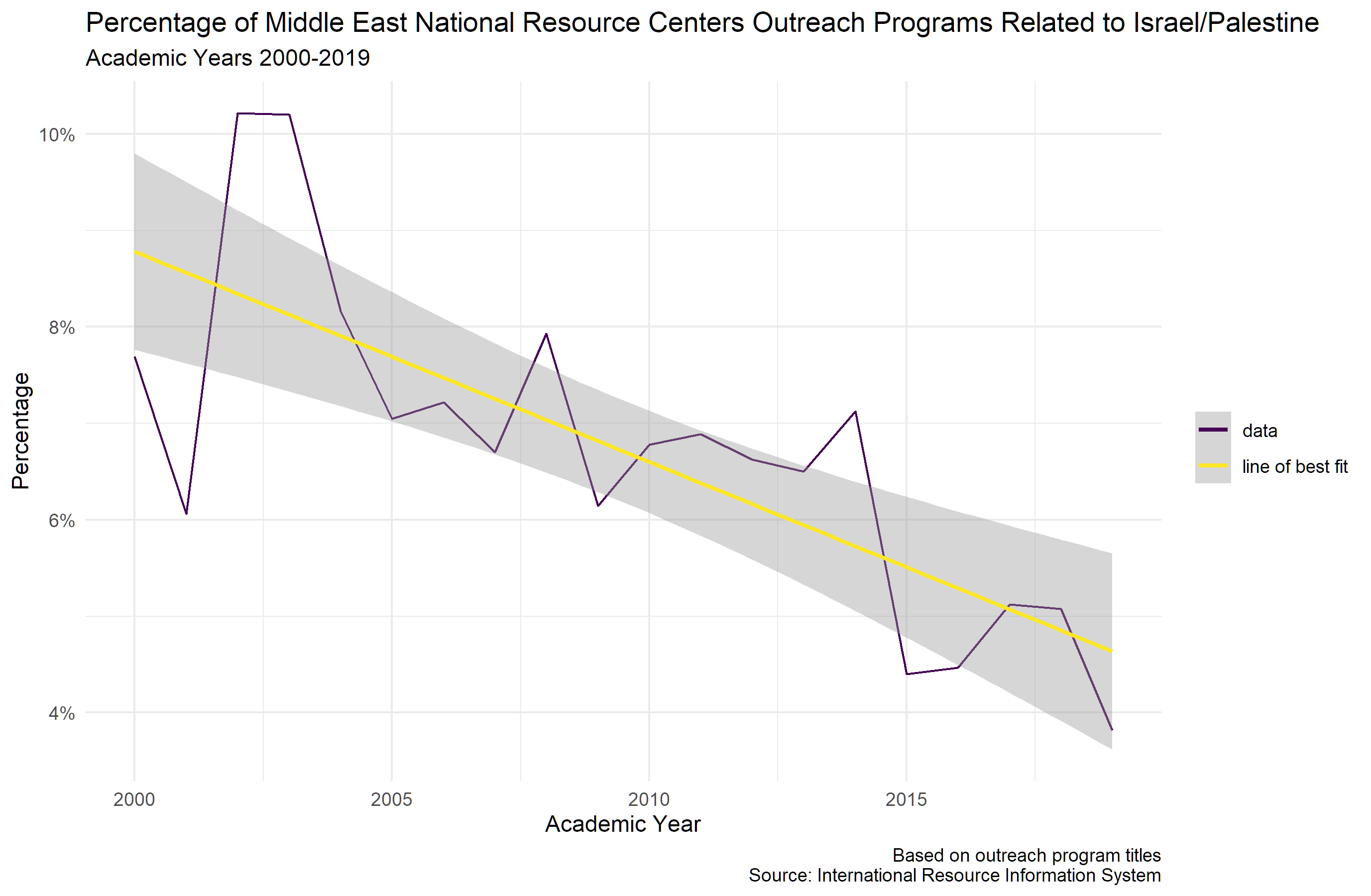

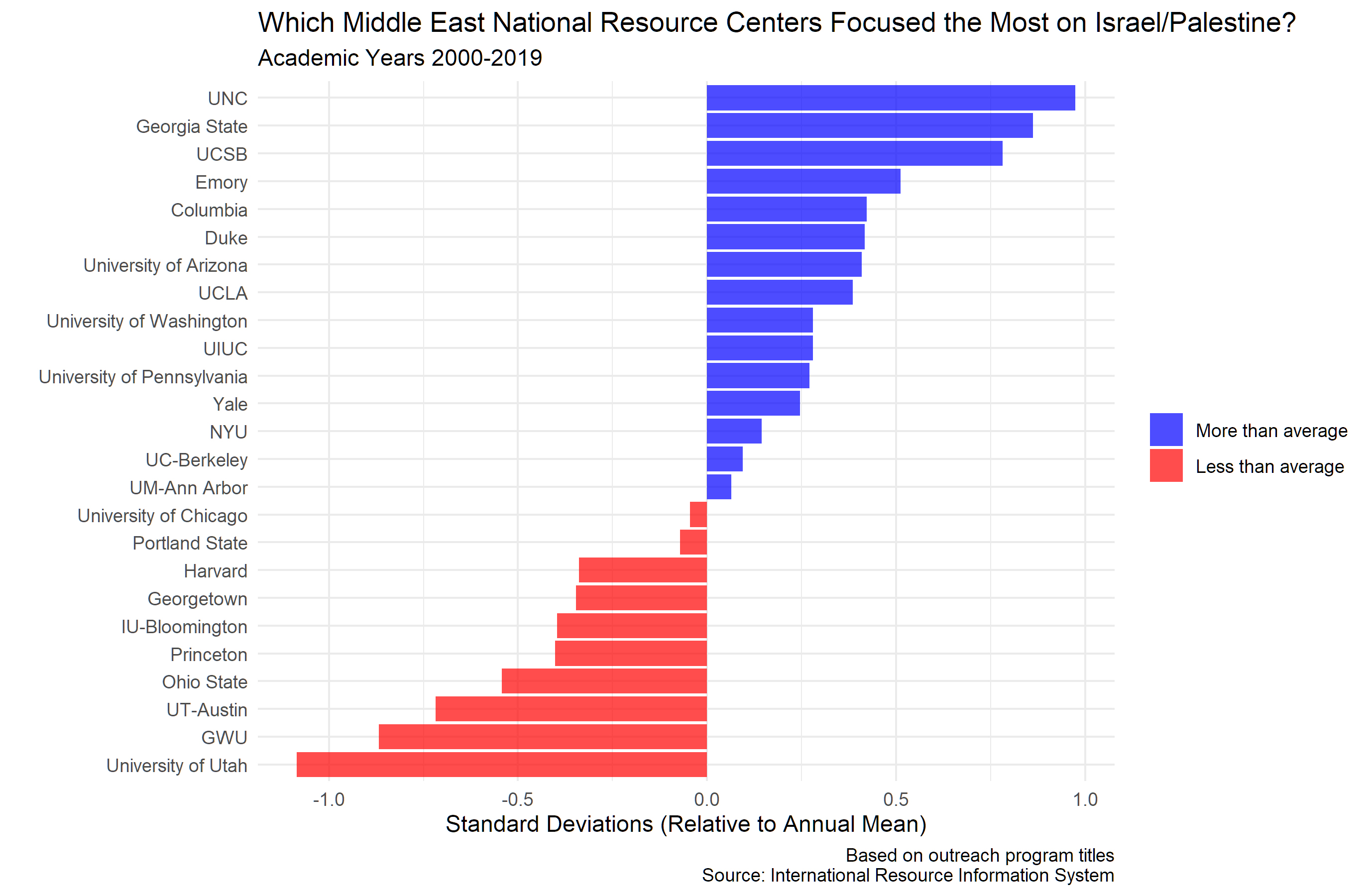

The trend in Middle East NRCs’ coverage of the Israel–Palestine debate is also revealing. This debate began in the early 20th century and remains a highly contentious issue in the Middle East today. The discipline of Middle East studies has received significant scrutiny for its pro-Palestinian partisanship, especially in recent years. Many of the faculty at MESCs support or are affiliated with the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement (BDS), which advocates for an aggressive economic embargo against Israel due to perceived injustices against Palestinians.

Figure 18