Abstract

A new movement in American higher education aims to transform the teaching of civics. This report is a study of what that movement is, where it came from, and why Americans should be concerned.

What we call the “New Civics” redefines civics as progressive political activism. Rooted in the radical program of the 1960s’ New Left, the New Civics presents itself as an up-to-date version of volunteerism and good works. Though camouflaged with soft rhetoric, the New Civics, properly understood, is an effort to repurpose higher education.

The New Civics seeks above all to make students into enthusiastic supporters of the New Left’s dream of “fundamentally transforming” America. The transformation includes de-carbonizing the economy, massively redistributing wealth, intensifying identity group grievance, curtailing the free market, expanding government bureaucracy, elevating international “norms” over American Constitutional law, and disparaging our common history and ideals. New Civics advocates argue among themselves which of these transformations should take precedence, but they agree that America must be transformed by “systemic change” from an unjust, oppressive society to a society that embodies social justice.

The New Civics hopes to accomplish this by teaching students that a good citizen is a radical activist, and it puts political activism at the center of everything that students do in college, including academic study, extra-curricular pursuits, and off-campus ventures.

New Civics builds on “service-learning,” which is an effort to divert students from the classroom to vocational training as community activists. By rebranding itself as “civic engagement,” service-learning succeeded in capturing nearly all the funding that formerly supported the old civics. In practice this means that instead of teaching college students the foundations of law, liberty, and self-government, colleges teach students how to organize protests, occupy buildings, and stage demonstrations. These are indeed forms of “civic engagement,” but they are far from being a genuine substitute for learning how to be a full participant in our republic.

New Civics has still further ambitions. Its proponents want to build it into every college class regardless of subject. The effort continues without so far drawing much critical attention from the public. This report aims to change that.

In addition to our history of the New Civics movement and its breakthrough moment when it was endorsed by President Obama, we provide case studies of four universities: the University of Colorado, Boulder (CU-Boulder), Colorado State University in Fort Collins (CSU), the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley (UNC), and the University of Wyoming in Laramie (UW).

We make four recommendations to state legislators across the country:

- Mandate a course in traditional American civics as a graduation requirement at all colleges and universities that receive public funding. If the institution itself is unwilling or unable to offer such a course, students must be permitted without penalty to meet the requirement by taking a qualified civics course at another institution.

- Establish a public body to set the guidelines for the required civics course, which should at a minimum teach the history, nature, and functions of our institutions of self-government, and which should aim to foster commitment to our form of self-government. The public body should also be charged with reviewing and approving civics textbooks to be used in these courses.

- Require that the traditional civics requirement be met only through classroom instruction. Service learning, civic engagement, or analogous extra-curricular activities will not be accepted as a substitute, supplement, or alternative.

- End funding for service-learning and civic engagement programs and bureaucracies.

Preface by Peter W. Wood

Civics is an old and integral part of American education, dating from the early years of the republic. Over the course of more than 200 years, instruction in civics changed in response to both national needs and pedagogical fads. This study examines the most recent of those changes, the rise of what we call the New Civics.

What is most new about the New Civics is that while it claims the name of civics, it is really a form of anti-civics. Civics in the traditional American sense meant learning about how our republic governs itself. The topics ranged from mastering simple facts, such as the branches of the federal government and the obligations of citizenship, to reflecting on the nature of Constitutional rights and the system of checks and balances that divide the states from the national government and the divisions of the national government from one another. A student who learns civics learns about voting, serving on juries, running for office, serving in the military, and all of the other key ways in which citizens take responsibility for their own government.

The New Civics has very little to say about most of these matters. It focuses overwhelmingly on turning students into “activists.” Its largest preoccupation is getting students to engage in coordinated social action. Sometimes this involves political protest, but most commonly it involves volunteering for projects that promote progressive causes. At the University of Colorado at Boulder, for example, the New Civics includes such things as promoting dialogue between immigrants and native-born residents of Boulder County; marching in support of the United Farm Workers; and breaking down “gender binary” spaces in education.

Whatever one might think of these activities in their own right, they are a considerable distance away from what Americans used to mean by the word “civics.” These sorts of activities are not something added to traditional civics instruction. They are presented as a complete and sufficient substitute for the traditional civics education.

From time to time, the press picks up on surveys that purport to show the astonishing ignorance of large percentages of college students when they are asked basic questions about the American political order. We hear that 35 percent of recent college graduates mistakenly believe that the Constitution gives the President the power to declare war; that only 28 percent correctly identified James Madison as father of the Constitution; and that more than half misidentified the elected terms of members of Congress.1 These glimpses of the state of civic knowledge may seem to reflect ill on the students, who seem not to remember the most basic elements of their instruction in civics. The truth, however, is that most of these students have never had any basic instruction in civics. They can’t be blamed for what they have never been taught. Their answers merely reflect the neglect of traditional civics instruction at every level of education, from grade school through college.

In issuing this report, the National Association of Scholars joins the growing number of critics who believe that some version of traditional civics needs to be restored to American education. This is a non-partisan concern. For America to function as a self-governing republic, Americans must possess a basic understanding of their government. That was one of the original purposes of public education and it has been the lodestar of higher education in our nation from the beginning.

The New Civics has diverted us from this basic obligation.

While many observers have expressed alarm about the disappearance of traditional civics education, very few have noticed that a primary cause of this disappearance has been the rise of the New Civics. This new mode of “civic” training is actively hostile to traditional civics, which it regards as a system of instruction that fosters loyalty to ideas and practices that are fundamentally unjust. The New Civics, claiming the mantle of the “social justice” movement, aims to sweep aside those old ideas and practices and replace them with something better.

The Aims of This Study

The deeper purpose of this report is to examine the replacement of traditional civics by New Civics. In this introduction, we give an overview of what the New Civics is and how it has muscled aside traditional civics. In the body of the report, we offer a deeper examination of the topic. Part One is a historical study of the rise of New Civics. Part Two consists of four case studies: the University of Colorado at Boulder, Colorado State University, the University of Northern Colorado, and the University of Wyoming. Part Three offers our assessments and recommendations.

The New Civics is a national development, not something limited to the Rocky Mountain States. While it has been in the works for decades, its official moment of arrival might be dated to the publication in 2012 of a White House commissioned study, A Crucible Moment: College Learning & Democracy’s Future. The publication of A Crucible Moment raised several questions for the National Association of Scholars: To what extent has the New Civics has already taken hold in American higher education? What precisely is the New Civics? And what is a proper alternative for civics instruction in higher education?

The first part of our answer to those questions was a forum in the fall 2012 issue of Academic Questions, which published critiques of A Crucible Moment from eminent scholars throughout the country, as well as their ideas for how to reform post-secondary civics education.2 This report is the second part of our answer.

The National Association of Scholars (NAS) is a non-partisan advocacy organization that upholds the standards of a liberal arts education. We view the liberal arts, properly understood, as fostering intellectual freedom, the search for truth, and the promotion of virtuous citizenship. From our founding in 1987, the topic of how higher education informs American self-governance has been among our chief concerns. NAS pursues this concern in a variety of ways, one of which has been the publication of in-depth research reports on what colleges and universities actually do in carrying out their civic mission.

This report thus follows in a long series of studies that have examined the public commitments and roles played by colleges and universities. Like our previous studies, it aims for depth and thoroughness—far more depth and thoroughness than typically is found in think tank-style studies. We believe our efforts to describe matters in such detail serve two important purposes. First, the search for the truth often requires the patience to gather and analyze a large body of facts. We believe that fair-minded thoroughness contributes more to the broader discussion than either anecdote or artificially narrow selection of data. Second, we describe matters in great detail because we believe in the value of context. Especially in describing long-term and complex phenomena, it is crucial to see how the various pieces come together—and where they fail to. Large-scale social and cultural developments have both internal consistencies and inconsistencies. Our studies aim to give due attention to both. Making Citizens is written in this spirit.

Complications

New Civics has appropriated the name of an older subject, but not the content of that subject or its basic orientation to the world. Instead of trying to prepare students for adult participation in the self-governance of the nation, the New Civics tries to prepare students to become social and political activists who are grounded in broad antagonism towards America’s founding principles and its republican ethos.

But a casual observer of New Civics programs might well miss both the activist orientation and the antagonism. That’s for two reasons. First, the New Civics includes a great deal that is superficially wholesome. Second, the advocates of New Civics have adopted a camouflage vocabulary consisting of pleasant-sounding and often traditional terms. Taking these in turn:

Superficial wholesomeness. When New Civics advocates urge college students to volunteer to assist the elderly, to help the poor, to clean up litter, or to assist at pet shelters, the activities themselves really are wholesome. Why call this superficial? The elderly, the poor, the environment, and abandoned pets—to mention only a few of the good objects of student volunteering—truly do benefit from these efforts. The volunteering itself is not necessarily superficial or misguided. But, again, context matters. In the context of New Civics, student volunteering is not just calling on students to exercise their altruistic muscles. It is, rather, a way of drawing students into a system that combines some questionable beliefs with long-term commitments. These seemingly innocent forms of volunteering, as organized by the patrons of New Civics, are considerably less “voluntary” than they often appear—especially since more and more colleges are turning such “volunteer” work into a graduation requirement. Some students even call them “voluntyranny,” given the heavy hand of the organizers in coercing students to participate. They submerge the individual into a collectivity. They ripen the students for more aggressive forms of community organization. And often they turn the students themselves into fledgling community organizers. For example, at the University of Colorado at Boulder, the program called Public Achievement includes a sub-program in which college students are sent out to organize grade school students into teams to pick up litter. This is certainly wholesome if taken in isolation, but in context, it is what we call superficially wholesome.

Camouflage vocabulary. The world of New Civics is rife with familiar words used in non-familiar ways. Democracy and civic engagement in New Civic-speak do not mean what they mean in ordinary English. We will deal with many of these terms more extensively when they come up in context, but it will help the reader to start with a rough idea of double meanings of the key words.

A Dictionary of Deception

ACTIVE

ENGAGED IN POLITICAL ACTION, AS OPPOSED TO THE PURSUIT OF KNOWLEDGE.

This is exemplified in a catchphrase used by Syracuse University’s civic program: “Citizen isn’t just something you are. Citizen is something you do.”3 The idea is that students aren’t getting a full education just by reading books, listening to lectures, writing papers, speaking in class, debating with each other, and participating in the social life of the college community. They must also “learn by doing.” Another phrase for this is that students should “apply their academic learning” or “practice” it in the real world. “Active” always means “active in progressive political campaigns.”

ALLIES

OUTSIDE SUPPORTERS OF A GRIEVANCE GROUP.

Non-blacks who support Black Lives Matter, men who support feminist groups, and non-gays who support LGBTQ groups are examples of allies. Allies are expected to defer in all cases to the opinions of the leaders of the grievance group they support. To venture an independent opinion, or worse, to suggest a criticism of the views or tactics of the grievance group is to invite an accusation of presumptuousness, betrayal, or infringement upon the grievance group’s “safe space.” An articulate ally must be made to shut up.

AWARENESS

ENLIGHTENED ABOUT THE ESSENTIAL OPPRESSIVENESS OF AMERICAN SOCIETY, ALTHOUGH NOT YET “ACTIVE.”

The “aware” student is up to date with the progressive party line, and knows the current list of oppressions that need to be righted. The “aware” student knows the true meaning of words: “academic freedom,” for example, is really “a hegemonic discourse that perpetuates the structural inequalities of white male power.” “Awareness” requires politically correct purchases and social interactions—reusable water bottles, fair-trade coffee, a diffident approach to pronouns—but it does not require active participation in a campaign of political advocacy. The “aware” student can move higher in the collegiate pecking order by accusing his peers of being less “aware.” Being “aware” requires a lower level of commitment than being “engaged.” “Awareness” is low-energy virtue-signaling.

CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

POLITICAL ACTIVISM ON BEHALF OF PROGRESSIVE CAUSES.

Thomas Ehrlich’s frequently cited Civic Responsibility and Higher Education (2000) defines “civic engagement” as “working to make a difference in the civic life of our communities and developing the combination of knowledge, skills, values and motivation to make that difference. It means promoting the quality of life in a community, through both political and non-political processes.”4 In practice, “civic engagement” hardly ever refers to participation in the machinery of government—jury duty, service in the armed forces, volunteer work as a fireman, and so on. “Civic engagement” overwhelmingly means “political activism for a progressive ‘community’ organization.” Alternative terms include “community engagement,” “democratic learning,” “civic pedagogies,” and “civic problem-solving.”

CIVIC ETHOS

DEFERENCE TO THE PROGRESSIVE IDEOLOGY OF NEW CIVICS ACTIVISTS.

“Civic ethos” refers to the character traits—the “dispositions” that support civic engagement, civic learning, and so on. These “dispositions” include Respect for freedom and human dignity; Empathy; Open-mindedness; Tolerance; Justice; Equality; Ethical integrity; and Responsibility to a larger good.5 Other people are supposed to be “tolerant” and “open-minded” toward progressives; progressives never have to be tolerant and open-minded toward other people.

CIVIC LEARNING

LEARNING PROGRESSIVE DOCTRINES, AND THE POLITICAL TACTICS NEEDED TO FORWARD THEM.

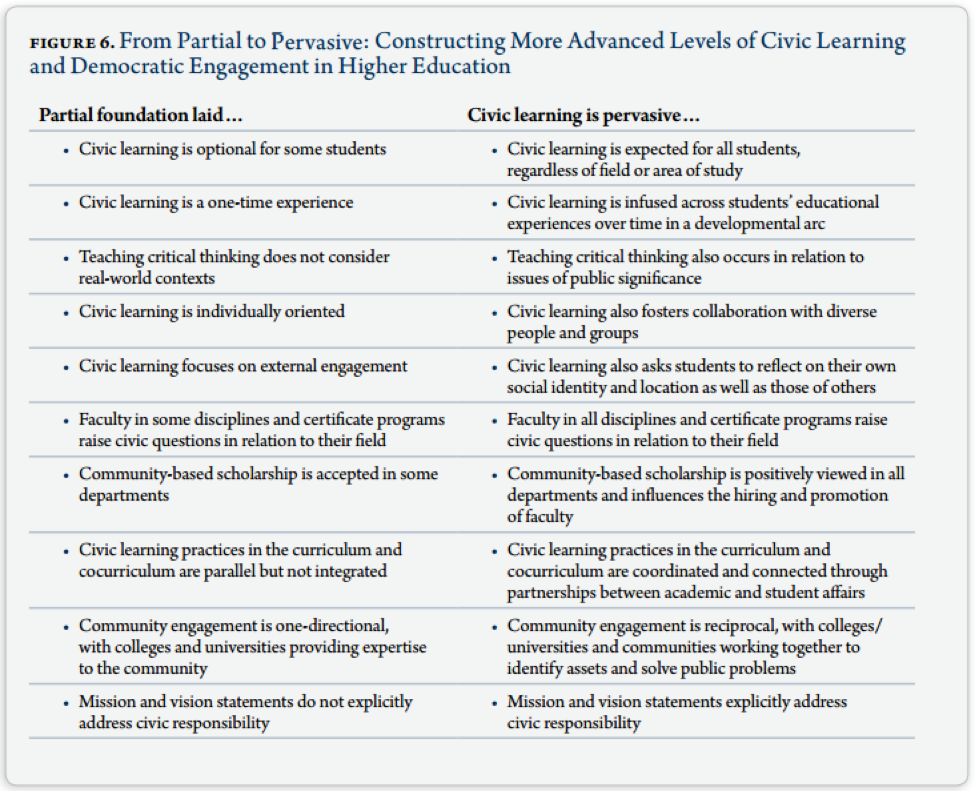

“Civic learning” is learning how to be properly civically engaged; civic learning, in other words, teaches students the content of progressives’ political beliefs, how to propagandize for them, and the means by which to enforce them on other people via the administrative state. New Civics advocates are trying to make progressive propaganda required for college students by calling “civic learning” an “essential learning outcome.” Civic learning is supposed to become “pervasive”—inescapable political education.

COMMITMENT

LOYALTY TO AND ENTHUSIASTIC PARTICIPATION IN A SOCIAL JUSTICE CAUSE.

“Commitment” is an enthusiastic form of being “active.” It signals a student’s readiness to make a career as a progressive advocate in a “community organization,” university administration, or the government. It also signals to progressives entrusted to hire new personnel that a student is a trustworthy employee.

COMMUNITY

A GROUP FOR WHOM PROGRESSIVES CLAIM TO ACT, OFTEN PUTATIVELY DEFINED BY A SHARED HISTORY OF SUFFERING.

A community is a group of people not defined by their civic status—citizens of America, Colorado, Denver, and so on. Precisely because communities have no civic or legal definition, New Civics advocates use the word to claim that they speak for a group of people, since the claim can never be falsified. While “community” can be used as a generic assertion of power by New Civics advocates, it is most often used 1) in reference to the “campus community,” as a way to assert power within the university; and 2) in reference to a local grievance group, usually but not exclusively poor blacks or Hispanics, on whose behalf progressives assert a moral claim so as to forward their political program.

COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION

MACHIAVELLIAN TACTICS TO INCREASE THE POWER OF THE RADICAL LEFT, FOLLOWING THE STRICTURES OF SAUL ALINSKY.

“Community organization” as a process refers to the Machiavellian tactics used by mid-twentieth-century radical Saul Alinsky to forward radical leftist goals. New Civics advocates use community organization tactics against the university itself, as they try to seize control of its administration and budget; they also train students to act as community organizers in the outside world. “Community organization” as a noun refers to a group founded by Alinskyite progressives, with Alinskyite aims. Community organization signifies the most intelligent and dangerous component of the progressive coalition.

CONSENSUS

A LOUDLY SHOUTED PROGRESSIVE OPINION, VERIFIED BY DENYING DISBELIEVERS THE CHANCE TO SPEAK.

Consensus means that everyone agrees. Progressives achieve the illusion of consensus by shouting their opinions, asserting that anyone who disagrees with them is evil, and preventing opponents from speaking—sometimes by denying them administrative permission to speak on a campus, sometimes literally by shouting them down. “Consensus” is also used as a false claim to authority, especially with reference to “scientific consensus.” Notably, “sustainability” advocates claim (falsely) that 97 percent of scientists believe that the Earth is undergoing manmade catastrophic global warming. Some scientists do, in fact, believe this, but the percentage is a fraction of the oft-repeated “97 percent.” The policy that follows from the 97 percent claim is government-forced replacement of fossil fuels, starting with coal, with expensive and unreliable “renewable sources” of energy. The advocates of consensus desire that nothing contrary to such scientific “consensus” should ever be taught in a university.

CRITICAL, CRITIQUE

DISMANTLING BELIEF IN THE TRADITIONS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION AND AMERICAN CULTURE.

To be critical, or to engage in critique, is to attack an established belief on the grounds that it is self-evidently a hypocritical prejudice established by the powerful to reinforce their rule, and believed by poor dupes clinging to their false consciousness. “Critical thought” sees through the deceptive appearance of freedom, justice, and happiness in American life and reveals the underlying structures of oppression—sexism, racism, class dominance, and so on. “Critique” works to dismantle these oppressive structures. “Critical thought” and “critique” is also meant to reinforce the ruling progressive prejudices of the universities; it is never to take these prejudices as their object.

DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY

THOUGHTFUL, RATIONAL DISCUSSION OF POLITICAL ISSUES THAT ENDS UP WITH PROGRESSIVE CONCLUSIONS.

Deliberative democracy is a concept that political theorists have drawn from Jürgen Habermas’ theory of communicative rationality. While formally about the procedures of democratic decision-making, it aligns with the idea of a transcendental, quasi-Marxist Truth, toward which rational decision-making inevitably leads. New Civics advocates in Rhetoric/Communications and Political Science departments frequently use “deliberative democracy” classes and centers as a way to forward progressive goals.

DEMOCRACY

PROGRESSIVE POLICIES ACHIEVED BY ARBITRARY RULE AND/OR THE THREAT OF VIOLENCE.

New Civics advocates use “democracy” to mean “radical social and economic goals, corresponding to beliefs that range from John Dewey to Karl Marx.” They also use “democratic” to mean “disassembling all forms of law and procedure, whether in government, the university administration, or the classroom.” A democratic political decision overrides the law to achieve a progressive political goal; a democratic student rally intimidates a university administration into providing more money for a campus New Civics organization; a democratic class replaces a professor’s informed discussion with a student’s incoherent exposition of his unfounded opinion. A democracy in power issues arbitrary edicts to enforce progressive dogma, and calls it freedom.

DIALOGUE

LECTURES BY PROGRESSIVE ACTIVISTS, INTENDED TO HARANGUE DISSIDENTS INTO SILENCE.

In “dialogue,” or “conversation,” students are supposed to listen carefully to a grievance speaker, usually a professional activist, and if possible echo what the speaker has to say. The dialogue is never between individuals, but between representatives of a race, a religion, a nationality, and so on. The structure of dialogue thus dehumanizes all participants by making them nothing more than mouthpieces for a group “identity.” Progressive “dialogue” presumes a progressive conclusion, and presumes that non-progressives have nothing worthwhile to say. Non-progressives engage in dialogue to learn the progressive things to say, or to learn how to shut up.

DIVERSITY

PROPAGANDA AND HIRING QUOTAS IN FAVOR OF MEMBERS OF THE PROGRESSIVE GRIEVANCE COALITION.

The Supreme Court used “diversity” as a rationale for sustaining the legality of quotas for racial minorities in higher education admissions, first in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) and then in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003). Academic bureaucrats therefore used the word intensively in the following decades.”Diversity” has spread out to the broader culture as a euphemism and a justification for racial discrimination. In recent years progressives have come to use it as a form of loyalty oath, requiring Americans to affirm diversity as a way to say that they support both the legality and the goodness of preferences for members of the progressive grievance coalition. Progressives cite “diversity” as a reason to prohibit opponents from speaking on campus.

EFFECTIVE

TIED TO A STABLE PROGRESSIVE ORGANIZATION.

When New Civics advocates talk about “effective” action they mean programs that outlast the immediate period of student engagement. Programs that have an enduring base within the “community” are effective. “Effective” action is action that supports a progressive “community organization,” and that is directed by that community organization.

ENGAGED CITIZENS

ENRAGED CITIZENS. COMMITTED ACTIVISTS.

Those who promote “civic engagement” on college campuses want students to become “engaged citizens,” as opposed to apathetic or self-interested individuals. An engaged citizen works for a progressive advocacy organization, to pressure the university administration or the government to enact progressive goals. Civic engagement never refers to accountable service in government, although it does sometimes refer to electing progressive activists into office, so as to enforce the progressive agenda via the power of the government.

EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

WHATEVER IS LEARNED BY DOING AS OPPOSED TO READING, STUDYING, LISTENING, ETC.

“Experiential learning” is a fancy way to say that reading an engineering textbook doesn’t teach you how to steady a steel beam at a construction site while the guy next to you is goldbricking. In the modern university, the phrase disguises the hollowness of undergraduate education: students take internships and other forms of “experiential learning” because the university has no solid classes to offer them. “Experiential learning” is also useful to businesses looking for unpaid labor. New Civics advocates use “experiential learning” as a way to justify “service-learning”—unpaid labor for progressive advocacy organizations, by way of training students to be progressive advocates.

GIVING BACK

EXPIATING UNEARNED PRIVILEGE BY SERVING A DESIGNATED GRIEVANCE GROUP.

“Giving back” or “paying forward” was originally a mawkish way of saying that you can pay back the good that has been done to you by doing good to someone else. Progressives use “giving back” to mean that ordinary Americans have received an unearned and sinful benefit of privilege, and must use their good fortune to work for designated grievance groups, presumptively unprivileged, in a way that a progressive organization thinks would be most useful. “Giving back” never refers to the gratitude students should feel for the hard work their parents have done to make a good life for them; “paying forward” never refers to hard work so as to make a good life for their own children.

GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP

DISAFFECTION FROM AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP IN FAVOR OF A NOTIONAL MEMBERSHIP IN A NON-EXISTENT GLOBAL STATE.

“Global citizenship” is a way to combine civic engagement, study abroad, and disaffection from primary loyalty to and love of America. A global citizen favors progressive policies at home and abroad, and is in favor of constraining the exercise of American power in the interest of American citizens. A global citizen is a contradiction in terms, since he is loyal to a hypothetical abstraction, and not to an actual cives—a particular state with a particular history. A global citizen seeks to impose rule by an international bureaucratic elite upon the American government, and the beliefs of an international alliance of progressive non-governmental organization upon the American people.

GRASSROOTS

PUTATIVELY NON-HIERARCHICAL PROGRESSIVE COMMUNITY ORGANIZATIONS.

The “grassroots” have democratic authenticity—they’re not professional politicians claiming to speak for the people, and they aren’t made to conform to any sort of hierarchical authority. Real grassroots— citizens coming together to lobby legislators—is intrinsic to the American political system, but when progressives claim to speak for the grassroots, and they mean a drive funded by George Soros and organized by paid activists. These activists declare that “consensus” has been reached by “the people” outside the formal structures of representative democracy. Since “consensus” is achieved by shouting down moderates, compromisers, and gentle souls, genuine progressive grassroots organizations make unaccountable ideological fanaticism the source of decision-making. See Black Lives Matter.

HIGH-IMPACT PRACTICES

SUCCESSFUL PROPAGANDA OR CONTROL OF STUDENTS.

A “high-impact practice” is education that works. Since New Civics advocates define education as progressive propaganda of students and the training of students to be progressive activists, they use “high-impact practice” to refer to effective propaganda and effective activist training. The AAC&U lists “first-year seminars and experiences”; “common intellectual experiences”; “learning communities”; “writing-intensive courses”; “collaborative assignments and projects”; “undergraduate research”; “diversity/global learning”; “service learning/community-based learning”; “internships”; and “capstone courses and projects” as examples of high-impact educational practices.6 This list reveals that these programs are now all used as instruments of the New Civics.

INCLUSION

GRANTING PRIVILEGES AND FUNDING TO A GRIEVANCE-BASED IDENTITY GROUP.

An inclusive college administration hires professors and staff who belong to an aggrieved identity group, under the misapprehension that funding grievance will make it go away. An inclusive student affairs staff will host endless celebrations of, by, and for the aggrieved identity group, silently acclaimed by all observers. An inclusive class spends a great deal of time celebrating aggrieved identity groups, in any subject from algebra to zoology. Inclusion, like diversity, is now used as a loyalty oath to affirm the legality and goodness of discrimination in favor of members of the progressive coalition of the aggrieved. Progressives cite “inclusion” as a reason to prohibit opponents from speaking on campus.

INTERDEPENDENCE

SINCE EVERYONE NEEDS EVERYONE, EVERYONE MUST DO WHAT PROGRESSIVES WANT.

“Ecological interdependence” means that we must destroy oil companies because flowers can’t bloom without bees. There is, of course, real interdependence, ecological and otherwise. Wolves need prey, and prey need wolves to keep down their numbers. The public and private sectors need one another. But “global interdependence” in the language of the progressive left means America must always do what other countries want, because we need them. “Interdependence” means “we are responsible to everyone else”—where responsible in turn means we must do what progressives tell us is for the common good. “Interdependence” universalizes the language of needs and rights, and therefore justifies the expansion of the progressive state to extend to every aspect of life. “Interdependence” means we are morally obliged to renounce our freedom to do as we will.

INTERSECTIONALITY

THE IDEA THAT EVERY COMPONENT OF THE PROGRESSIVE LEFT MUST SUPPORT ALL OTHER COMPONENTS OF THE PROGRESSIVE LEFT.

“Intersectionality” is a way to align progressives’ competing narratives of oppression and victimhood by making every purported victim of oppression support every other purported victim of oppression. Progressive advocates for racial discrimination (“diversity”) must support progressive advocates for suppressing religious freedom (“gay rights”), and vice versa. Practically speaking, the greatest effect of “intersectionality” is that BDS activists—pro-Palestinian activists pushing for the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctioning of Israel—are using it as a rationale to remove Jews from positions in campus leadership and from jobs as progressive activists.7 Intersectionality is both a way to whip progressive activists into following a broader party line and, increasingly, a rationale for anti-Semitic discrimination by progressives.

PERVASIVENESS

MAKING NEW CIVICS INESCAPABLE AT THE UNIVERSITY.

The New Civics seeks to insert progressive advocacy into every aspect of higher education, inside and outside the college. A Crucible Moment summons higher education institutions to make civic learning “pervasive” rather than “peripheral.”8 “Pervasiveness” justifies the extension of progressive propaganda and advocacy by student affairs staff and other academic bureaucrats into residential life and “co-curricular activities”—everything students do voluntarily outside of class. It also justifies the insertion of progressive advocacy into every class, as well as making progressive activism a hiring and tenure requirement for faculty and staff.

RECIPROCITY

CONTROL BY PROGRESSIVE COMMUNITY ORGANIZATIONS.

Service-learning is founded on the idea that the student who volunteers should also be transformed. The student gives to the community, but in turn learns from the community, reciprocally. This basic idea has been transformed into a euphemism for control by progressive community organizations, since you can’t learn unless the “community” tells you what to do and think. “Reciprocal” is a sign that progressive organizations have seized control of university funds.

SERVICE-LEARNING

FREE STUDENT LABOR FOR PROGRESSIVE ORGANIZATIONS; TRAINING TO BE A PROGRESSIVE ACTIVIST.

“Service-learning” was invented in the 1960s by radicals as a way to use university resources to forward radical political goals. It aims to propagandize students (“raise their consciousness”), to use their labor and tuition money to support progressive organizations, and to train them for careers as progressive activists. It draws on educational theories from John Dewey, Paulo Freire, and Mao’s China. Since the 1980s, “service-learning” has used the name “civic engagement” to provide a “civic” rationale for progressive political advocacy. Civic engagement, global learning, and so on, all are forms of service-learning.

SOCIAL JUSTICE

PROGRESSIVE POLICIES JUSTIFIED BY THE PUTATIVE SUFFERINGS OF DESIGNATED VICTIM GROUPS.

Social justice aims to redress putative wrongs suffered by designated victim groups. Unlike real justice, which seeks to deliver individuals the rights guaranteed to them by written law or established custom, social justice aims to provide arbitrary goods to collectivities of people defined by equally arbitrary identities. Social justice uses the language of law and justice to justify state redistribution of jobs and property to whomever progressives think deserve them. Since social justice can never be achieved until every individual’s consciousness has been raised, social justice also justifies universal political propaganda, to make every human being affirm progressivism, and not just obey its dictates.

SUSTAINABILITY

GOVERNMENTAL TAKEOVER OF THE ECONOMY TO PREVENT THE IMMINENT DESTRUCTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT.

“Sustainability” translates thrift, conservation, and environmentalism into a political program aimed at subjugating the free-market economy, as the necessary means to avert “climate change.” It also requires propaganda to kill the desires in people that lead to burning fossil fuels. Since the environment is a “global problem,” the sustainability agenda dovetails with “global citizenship.”

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SKILLS

DIGITAL MEDIA SKILLS USED TO FORWARD THE PROGRESSIVE AGENDA.

The ability to use social media and graphic design for progressive propaganda and organization. The emphasis on “skills” generally argues that universities don’t need to teach any body of knowledge; the particular emphasis on “twenty-first century skills” further argues that universities don’t need to teach anything discovered before the year 2000. Recent college graduates use “twenty-first century skills” as an argument that they should be employed despite knowing nothing and having no work experience.

A Crucible Moment?

The definitions we have sketched in the preceding section voice our distrust of the New Civics movement. Its declarations about its aims and its avowals about its methods can seldom be taken at face value. This isn’t a minor point. Civics in a well-governed republic has to be grounded on clear speaking and transparency. A movement that goes to elaborate lengths to present a false front to the public is not properly civics at all, no matter what it calls itself.

We began this study in the hope of finding out how far the New Civics had succeeded in becoming part of American colleges and universities. We came to a mixed answer. New Civics is present to some degree at almost all colleges and universities, but it is much more fully developed and institutionalized at some than it is at others. In our study, the University of Colorado at Boulder stands as our example of a university where New Civics has become dominant. But even at universities where New Civics has not attained such prominence, it is a force to be reckoned with. We show what that looks like at the University of Northern Colorado, Colorado State University, and the University of Wyoming.

The word “civics” suggests that students will learn about the structures and functions of government in a classroom. Some do, but a major finding of our study is that there has been a shift of gravity within universities. New Civics finds its most congenial campus home in the offices devoted to student activities, such as the dean or vice president for students, the office of residence life, and the centers for service-learning. Nearly every campus also has some faculty advocates for New Civics, but the movement did not grow out of the interests and wishes of mainstream faculty members. A partial exception to this is schools of education, where many faculty members are fond of New Civics conceits.

The positioning of New Civics in student services has a variety of implications.

First, it means the initiative is directly under the control of central administration, which can appoint staff and allocate budget without worrying about faculty opinion or “shared governance.” Programs like this can become signature initiatives for college presidents, and few within the university, including boards of trustees, have any independent basis to examine whatever claims a college president makes on behalf of New Civics programs. In a word, such programs are unaccountable.

Second, the positioning of New Civics as parallel to the college’s actual curriculum frees advocates to make extravagant claims about its contributions to students’ general education. New Civics is full of hyperbole about what it accomplishes, and even so, it vaunts itself as deserving an even larger role in “transforming” students. Its goal is to be everywhere, in all the classes, and in that sense to subordinate the teaching faculty to the staff who run the student services programs.

Third, the New Civics placement in student services tends to blur the line between academic and extra-curricular. New Civics advocates may hold adjunct appointments on the faculty. Frequently they push for academic credit for various forms of student volunteering. In general they treat the extra-curricular as “co-curricular,” which is rhetorical inflation.

New Civics is about seizing power in society, and the place nearest at hand is the university itself. New Civics mandarins are ambitious, and what starts in student services doesn’t stay there.

History

In Part I of the report, we trace New Civics to its origin in the 1960s as part of the radicalization of the teachings of John Dewey and the influence of the Marxist pedagogue Paulo Freire. The two ideas born of these influences were that students are better served by being made to “do” things than they are by teaching them with books and ideas, and that the only truly legitimate purpose of education is to achieve a progressive reordering of society. Put together, these premises lead to a single conclusion: students should be initiated into the life of social activism. The purpose of “school” is to turn as many students as possible into community organizers.

While these ideas won many fervent advocates from the 1960s through the 1980s, and became dominant at a few wayward colleges, they failed to persuade the vast majority of faculty members and college administrators. They were instead the preoccupation of a radicalized fringe, often based in schools of education.

During this period, however, higher education was engaged in three other developments that would eventually open the way for the New Civics activists.

Curricular Vacuum

First, colleges and universities dismantled their core curricula and general education requirements. Formerly students had been required to take a collection of specific courses, such as Western Civilization, American History, Calculus, English Composition, and Literature. These courses were required both in their own right and as prerequisites to more advanced courses. This system of instruction was replaced by one that relaxed requirements in favor of “choice.” Colleges varied to the degree in which choices were constrained. Some, such as Brown University, essentially left it up to students to take whatever courses they wanted, subject only to departmental restrictions. Many other colleges settled on “distribution requirements,” which required students to take at least one course in each of several categories, such as “humanities,” but left the student to choose among dozens or even hundreds of courses that met the requirement. Sometimes these distribution requirements have been falsely presented to the public as a “core curriculum,” but that is at best a drastic redefinition of the term. Distribution requirements, unlike a core curriculum, do not ensure that all the students at a college study any particular body of knowledge.

The National Association of Scholars in several previous reports has examined how the elimination of required courses reshaped American higher education. In The Dissolution of General Education 1914-1993 (1996)9, we tracked the disappearance of courses with prerequisites, and showed that the elimination of core curricula resulted in a “flatter” curriculum. The ideal of surmounting a difficult subject step by step, each course building on the last, survived in the sciences, foreign languages, and some technical fields, but it was lost in most of the humanities and social sciences.

Note that civics was one of the subjects that was swept away as a general education requirement and as a stepping stone to more advanced courses.

In our study The Vanishing West (2011)10 we tracked the disappearance of Western Civilization survey courses from 1964—when they were still required at most colleges and universities—to 2010, by which time they were an extreme rarity. In What Does Bowdoin Teach? How a Contemporary Liberal Arts College Shapes Students (2013)11 we traced in fine detail the disastrous consequences of one college’s decision in 1970 to jettison all general education requirements. In our series of reports titled Beach Books12, NAS has examined the common reading programs that many colleges have created in recent years as a way to conjure a modicum of intellectual community in the entropy of the post-core-curriculum campus. Having read nothing else in common, students are encouraged to read a single book, which often turns out to be a book that praises social activism. Examples include Wine to Water: How One Man Saved Himself While Trying to Save the World; Shake the World: It’s Not About Finding a Job, It’s About Creating a Life; and Almost Home: Helping Kids Move from Homelessness to Hope.

Into the curricular vacuum left after the formal version of general education was removed has stepped the New Civics with its comprehensive dream of turning all students into progressive activists.

Mass Higher Education

American higher education in the last half century underwent an enormous expansion. In 1960 about 45 percent of high school graduates attended college. By 1998, more than 65 percent did—a figure that has remained fairly stable since, topping out at 70 percent in 2009.13 That translates into more than 17 million students enrolled in undergraduate studies, with another 3 million enrolled in graduate programs. With the huge increase in students came plummeting standards of admission. The newer generations of college students could not be counted on to have studied or to know things that preceding generations studied and knew, such as the basics of civics. Mass higher education coupled with the dismantling of general education standards ensured that many of these students would never be taught knowledge that previous generations considered basic.

Mass higher education brought greater demographic diversity to the nation’s campuses, but it also laid the seeds for the ideology of “diversity.” The ideology is to be sharply distinguished from the demographic facts. As an ideology, diversity is a recipe for racial and ethnic antagonism. It offers a superficial vision of peaceful interdependence among identity groups, but at the same time it stokes resentments based on the idea that each of these groups has grievances at the core of their American experience, and that these grievances justify a policy of permanent racial quotas.

Civics that embraces the ideology of diversity is civics that treats the ideals of American unity and common experience as illusions. The New Civics plays off American mass higher education as an opportunity to emphasize inequity and unfairness in the nation’s racial and ethnic history and in the current distribution of wealth and power. Attending college itself is portrayed not as a privilege to be earned but as a right that has been historically denied to members of oppressed groups.

Dismantling (Some) Authority

The end of general education requirements and the rise of mass higher education are two of three pre-conditions for New Civics. The third is the dismantling of in loco parentis—the efforts that colleges formerly took to regulate the behavior of students on campus through well-enforced rules. The rules included such things as single-sex dorms, bans on underage drinking, and parietal hours. The end of in loco parentis was connected with the protests of the 1960s and the sexual revolution. But as college moved out of the work of building and fostering normative communities of students on campus, students felt more and more adrift. Reports in the late 1980s registered that one of the chief complaints of college students was “lack of community on campus.” Into this breach stepped the campus bureaucrats responsible for student activities. There followed a series of manifestos from student life organizations that they knew how to bring “community” back to campus. These were among the first steps to programs that elevated “student engagement” over academic study.

The Presidents Step In

These developments made it possible for the New Civics to grow—but it was Campus Compact, an organization of college presidents, which provided the fertilizer. In 1985 service-learning radicals hijacked the newly-founded Campus Compact’s volunteering initiative, and from that moment on hundreds of college presidents began to shovel money and official support to service-learning. At the same time the New Civics advocates started referring to service-learning as civic engagement— a coat of new paint meant to give service-learning a higher status and the appearance of uplifting enterprise. It also helped to paint over the progressive propaganda that was a little too nakedly on display in Service-learning, where the service was typically to a leftist cause. What happened next illustrates the powers of college presidents to shift the course of higher education. The New Civics went from strength to strength in the next decades, both as a revolution from above and as a paycheck for a growing army of civic engage-o-crats.

The New Civics is now everywhere in American higher education—not just as civic engagement, but also as global learning, global civics, civic studies, community service, and community studies. The New Civics is also endemic in leadership programs, honors programs, co-curricular activities, orientation, first-year experience, student affairs, residential life, and more. The New Civics advocates use a variety of labels for their programs, but the vocabulary is much the same. Office of Civic Engagement & Leadership (Towson University), Office of Civic and Community Engagement (University of Miami), Office of Student Leadership and Engagement (University of Tampa), Office of Civic Engagement & Service Learning (University of Massachusetts), Office of Experiential Education and Civic Engagement (Kent State University), Office of Civic Engagement and Social Justice (The New School’s Eugene Lang College), Office of Community and Civic Engagement (University of North Carolina, Pembroke), Office of Civic Engagement and Social Responsibility (CUNY Brooklyn College), Office of Civic and Social Responsibility (University of Nebraska, Omaha), Office of Community-Engaged Learning (Southwestern University), Office of Service Learning and Community Engagement (University of Montevallo), Office of Global Engagement (University of Mississippi), Office of Citizenship and Civic Engagement (University of New England)—there are thousands of these offices across the country, and Centers and Initiatives and Programs too. They all use the same buzzwords and they all do the same thing—progressive propaganda, training cadres of progressive student activists, and grabbing hold of university resources and routing them to off-campus progressive organizations.

National Infrastructure

When we speak of New Civics, we are referring to more than a scattering of like-minded programs at the nation’s many colleges and universities. A national infrastructure buttresses these programs. The Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) finances and coordinates the New Civics with dozens of other activist organizations. Career bureaucrats of the Department of Education use their regulatory power and grant money to aid the New Civics. The accreditation bureaucracies that determine whether a college or university is eligible to receive federal money push “learning goals” that can only be satisfied by creating New Civics programs—and college bureaucrats slip in New Civics programs in the guise of satisfying accreditation “learning goals.” Professional organizations, journals, conferences, and job lists create standard career paths that New Civics advocates can pursue in virtually every college or university. Most important, an ever-growing number of administrators, faculty, and students ensconced as student life officers, education professors, and the like put advocacy of the New Civics at the center of their lives. Each new program plugs into a national network—and follows the example of older programs as it works to take over a new university.

Any effort to change the New Civics on a single campus has to take account of the fact that it is part of an ideologically committed national movement.

Revolutions Soft and Hard

New Civics is dedicated to radical politics, but some programs use softer means. Service-learning is the most innocuous, civic engagement more political, and Harry Boyte’s neo-Alinskyite chain of Public Achievement franchises, which uses college students to organize K-12 students, is the most hard-edged of all. The different forms of New Civics are ultimately variants on the techniques and goals of radical community organization. Service-learning might involve something as innocuous as organizing students to pick up litter from a park—but the point is to accustom them to organizing and being organized, and to “raise their consciousness” in a progressive direction. The New Civics draws students ever farther into the world of progressive politics, seeking to make as many as possible into full-time activists—or at the very least, into full-time academic administrators. Soft-edged or hard-edged, all New Civics steadily pulls students toward progressive activism—pretending to be a nonpartisan civic effort, and on the taxpayer’s dime.

The New Civics advocates redefine “civic” around the techniques of radical activism and discard the idea that civics should provide students a non-partisan education about the mechanisms of government. They likewise redefine “civic” to include the political goals of progressive politics, and they exclude any cause that contradicts progressive goals. The New Civics defines civics to include advocacy for illegal immigrants and “sustainability,” along with the rest of the progressive agenda—but so far as we can tell, not one of the millions of hours spent by students each year on community service, service-learning, and civic engagement has included service for organizations that forward (for example) Second Amendment rights, pro-life advocacy, or traditional marriage. The mission statements of the New Civics virtually define such work as uncivic. It is bad enough that the New Civics is a progressive advocacy machine—but it is worse that the New Civics advocates teach their narrow-minded ideological intolerance to America’s youth as civic religion. The fundamental lesson of the New Civics is that anyone who isn’t progressive is un- American—and to be treated as an enemy of the state.

Ambitions

The New Civics advocates aren’t satisfied with what they’ve already achieved. A Crucible Moment outlined what they want to do now—to make New Civics classes mandatory throughout the country, to make every class “civic,” and to require every teacher to be “civically engaged.” In short, they want to take over the entire university. After that, the New Civics advocates want to take over the private sector and the government as well. Every business and every branch of government is meant to support civic engagement. The same subterfuge that has been used to organize the university will be used to organize the country.

The New Civics advocates have already had disturbing success. More and more colleges are requiring students to take New Civics courses, and the Strategic Plans of universities throughout America now talk about “infusing civic engagement” into every class and every “co-curricular” activity. Every day, the New Civics advocates are pressing forward with their stated plan to take over America’s colleges and universities. They will continue to push to enact every part of their agenda.

Civic Engagement Now: Protest for Every Occasion

That’s for the future—but the New Civics advocates have already changed the country. The point of the New Civics was to create a cadre of permanent protestors, and justify their agitation as “civic”—and they have succeeded. I write this Preface in November 2016, and civic engagement is behind today’s headlines. A few days ago, high-school students around the country walked out from school to protest the election of Donald Trump—and “youth development leaders see the youth-led walkouts as a highly positive form of civic engagement.” Ben Kirshner, the director CU-Boulder’s New Civics program CU Engage, thinks these protests “are a really important statement of dissent.” But he’s only in favor of street protest so long as the protestors don’t express “racist or sexist ideas.” Amy Syvertsen of the Search Institute specifies that “When people make public statements that are driven from a place of hate, and when they minimize the political and civil rights of others, that is a negative form of civic engagement that crosses the line.”14 In other words, radical left protests intended to delegitimate Donald Trump’s presidency before it begins are civic engagement, but any support of Donald Trump crosses the line.

That’s just the New Civics encouraging protest—but the New Civics are also crossing a bright line and starting to fund that protest directly. At Pomona College, the Draper Center for Community Partnerships advertized a November 9 anti-Trump rally in Los Angeles on Facebook and reimbursed transportation costs for students to attend. The Draper Center personnel knew what they were doing: “The Draper Center is organizing a bus that will take students to downtown LA TONIGHT to stand against Trump.” As a result, Pomona College is being sued for violating its 501(c)(3) status, and is liable to sanctions up to and including losing its tax-exempt status.15

The New Civics has been grossly politicized for decades, but now it’s beginning to use university money for directly political activity. The New Civics advocates have preached the identity of progressive politics and civic activity for so long that they’ve forgotten the difference. Draper’s funding of anti-Trump political activity shows where the New Civics is heading nationwide. It also reveals a weakness of the New Civics advocates. They can be sued for political activity, and they can do grave fiscal damage to their host universities in the process. The NAS recommends that citizen groups around the nation look closely at what the New Civics programs in universities are doing, and that they sue their host universities for each and every political act they commit. Lawsuits, and the threat of lawsuits, may actually prod academic administrators to shut down New Civics programs.

This is an extreme remedy, but a necessary one. The New Civics has been creating activist-protestors for decades, but they have now achieved a critical mass. Look at any radical left protest, and like as not you will find a New Civics program somewhere in the background. As the New Civics grows stronger, so will the drumbeat of radical left agitation. Radical demonstration on our streets is now chronic, and that is an achievement of the New Civics. The New Civics is working to make such radical protest a daily occurrence, and America ungovernable save along progressive lines. The New Civics revolution has already begun.

Solutions

If service-learning, civic engagement, and global civics were just ideas that had bubbled up independently in a few colleges and universities, we would only recommend the reform of the programs that carry them out. NAS recommends that the New Civics be removed root and branch from higher education precisely because each individual program is part of a national movement that is ideologically committed toward radical left politics, with enormous reservoirs of bureaucratic power to repel any attempt to reform it. The New Civics cannot be reformed; it can only be dismantled. And it should be dismantled as soon as possible, before it does worse damage to our country.

The New Civics advocates must be stopped—but they won’t be stopped on campus. There are too many academic administrators and faculty pushing the New Civics forward, and too few who want to resist its progress. Lawsuits can help, but clever New Civics advocates can figure out how to avoid direct political activity. The Department of Education can’t be trusted to help either—although support from political appointees by the incoming Trump administration might make the campaign to eradicate the New Civics easier, too many of the Department’s permanent bureaucrats are allies of the New Civics advocates. State and federal legislatures have to do the hard work of defunding the New Civics. They need to freeze New Civics spending at once, and move swiftly to eliminate New Civics programs entirely. Making Citizens provides detailed suggestions about how precisely this could be done—for example, by tying government funding of universities to reestablishing traditional civic literacy curricula and removing the compensation of class credit from volunteer work. But we make our suggestions in all humility. The disposition of the New Civics is for legislators to decide.

The Full Report

I have written this preface so as to give the full political and educational context of the full report of Making Citizens. I invite the reader to turn now to that work. The first section of the report includes an examination of the history, the present condition, and the ambitions of the New Civics. The second section provides case studies of the decay of the Old Civics and the rise of the New Civics at four universities—the University of Colorado, Boulder; Colorado State University; the University of Northern Colorado; and the University of Wyoming. The end of the report contains our recommendations for how to restore civics education in America to good health.

The New Civics advocates have written histories of their efforts for one another, as a way to give pointers on how to do their work more effectively. We believe this report is the first book-length examination of the New Civics addressed to a general audience—the first report to reveal precisely what the New Civics advocates are doing in the guise of civics education. We look forward to what we know will be a thoughtful critique and development of the ideas presented here. We also look forward to action that will bring an end to the New Civics’ hostile takeover of American higher education.

Introduction

The New Civics movement has taken over America’s civics education, with the goal of redefining civics education as progressive (=radical left) political activism. The pioneers of this movement, originally members of the 1960s radical left, took advantage of the demolition of the old civics curriculum in the 1960s. The Old Civics had focused on basic civic literacy—knowledge about the structure of our government and the nature of America’s civic ideal--so as to prepare young men and women to participate in the machinery of self-governance. The 1960s radicals replaced the Old Civics with a New Civics of their own, devoted instead to preparing young men and women to be progressive activists.

This New Civics began as “service-learning,” and slowly established itself in the next decades in the fringes of higher education. Service-learning feeds off the all-American impulse to volunteer and do good works for others, and diverts it toward progressive causes. For example, service-learning channels the urge to clean up litter from a local park toward support of the anti-capitalist “sustainability” movement. Service-learning’s main goals in higher education are:

- to funnel university funds and student labor to advertise progressive causes.

- to support off-campus progressive nonprofits—“community organizations.”

- to radicalize Americans, using a theory of “community organization” drawn explicitly from the writings of Saul Alinsky, a mid-twentieth-century Chicago radical who developed and publicized tactics of leftist political activism.

- to “organize” the university itself, by campaigning for more funding for service-learning and allied progressive programs on campus. These allied programs include “diversity” offices, “sustainability” offices,” and components of the university devoted to “social justice.”

Service-learning was created in order to divert university resources toward progressive causes.

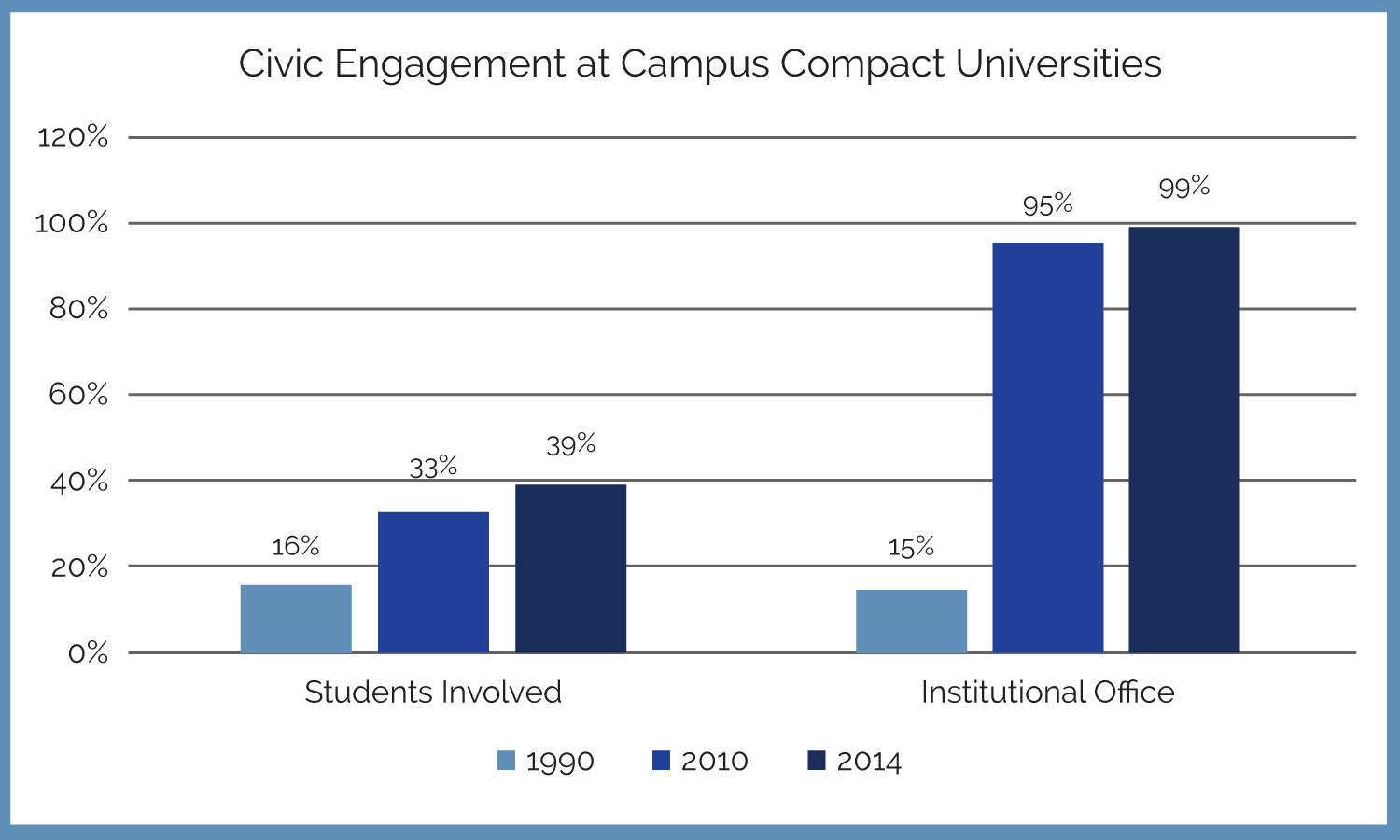

In 1985, several influential university presidents founded Campus Compact to support student volunteerism and community service. Service-learning advocates took over Campus Compact’s campaign, and from that vantage point inserted service-learning into virtually every college in the nation. They then gave service-learning a new name—“civic engagement”—and used this new label as a way to replace the old civics curriculum with service-learning classes. Service-learning and civic engagement together form the heart of the New Civics.

The New Civics is now endemic in higher education:

- The presidents of more than 1,100 colleges, with a total enrollment of more than 6 million students, have signed a declaration committing their institutions to “educate students for citizenship.”16

- The American Democracy Project, an initiative of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) in partnership with the New York Times that now includes 250 AASCU-member colleges and universities, seeks to “produce graduates who are committed to being knowledgeable, involved citizens in their communities.”17

- Seventy-one community colleges have signed The Democracy Commitment, a pledge to train students “in civic learning and democratic practice.”18

- More than 60 organizations and higher education institutions participating in the Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Action Network (CLDE) have submitted statements committing them to “advance civic learning and democratic engagement as an essential cornerstone for every student.”19

- The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching awarded a “Community Engagement Classification” to 240 colleges and universities in 2015.20

As of 2016, the “civic engagement” movement—a combination of federal bureaucrats, nonprofit foundations, and a network of administrators and faculty on college campuses—has already succeeded in replacing much of the old civics education. It now aims for a broader takeover of the entire university. The goal is to give every class a “civic” component, and to make “civic engagement” a requirement for tenure. The advocates of “civics education” now aim to insert progressive politics into every aspect of the university, to advertise progressive causes to the student body in every class and every off-campus activity, and to divert even larger portions of the American university system’s resources toward progressive organizations.

The New Civics advocates want to redefine the entire American civic spirit to serve the progressive political agenda—which is hostile to the free market; supports racial preferences in the guise of diversity; supports arbitrary government power in the guise of sustainability; and undermines traditional loyalty to America in the guise of global citizenship.

The New Civics has replaced the Old Civics, which fostered civic literacy. In consequence, American students’ knowledge about their institutions of self-government has collapsed. According to the Association of American Colleges & Universities’ report A Crucible Moment: College Learning & Democracy’s Future (2012), “Only 24 percent of graduating high school seniors scored at the proficient or advanced level in civics in 2010, fewer than in 2006 or in 1998,” “Half of the states no longer require civics education for high school graduation,” and “Among 14,000 college seniors surveyed in 2006 and 2007, the average score on a civic literacy exam was just over 50 percent, an ‘F’.”21

What the New Civics has produced instead is a permanently mobilized cadre of student protestors, ready to engage in “street politics” for any left-wing cause. In November 2016, for example, when high-school students around the country walked out from school to protest the election of Donald Trump, New Civics advocates described “the youth-led walkouts as a highly positive form of civic engagement.”22 Civic education ought to teach students how presidents are elected, not to engage in political warfare that denies the legitimacy of their fellow citizens’ choice for the presidency.

The New Civics also disguises the collapse of solid education in colleges. The universities’ resort to internships and “experiential education” already conceded that students do not have four years worth of material to study. Now “service-learning” and “civic engagement” classes transform what was at least useful work experience, if not really a college class, into vocational training for work as progressive community organizers—or for careers in college administration running New Civics programs. While the main goals of the New Civics are to advertise progressive causes and divert university resources to progressive organizations, it also works to disguise collapsing standards in education, train community activists, and prepare new personnel to administer New Civics programs.

The New Civics further damages colleges and universities by hollowing out the ideals and the institutional frameworks of a liberal arts education. A liberal arts education aims to introduce a student to the best works of the Western tradition, partly to educate his character toward personal and civic virtue and partly to foster the individuation of character that allows each person to commit himself, as an individual, to private success and public duty. The educational structure that supports the liberal arts takes this education of character to be the first purpose of a college, and one which needs no further justification. In addition to warping the definition of civic virtue by redefining it as commitment to progressive politics, the New Civics also eliminates the idea that the education toward virtue is meant to precede political action, and instead substitutes political action in place of education toward virtue. The New Civics likewise eliminates the liberal arts’ aim to foster the individuation of character, and replaces it with forced mobilization within a community, characteristically defined by race, class, and/or gender rather than by American citizenship. The New Civics then remakes the institutional structure of higher education in its own image: the core curricula that fostered a liberal arts education have been removed, and a new set of core curricula centered on civic engagement, global citizenship, and so on, is rising in their place. The New Civics assumes that a liberal arts education cannot justify itself.

The New Civics’ advocates are very optimistic about their ability to carry out an educational revolution, and they are not yet in a position to carry out all their plans. Yet they have already achieved great success, by following Saul Alinsky’s intelligent recommendation to focus upon capturing institutions and building enduring organizations. The number of New Civics advocates has grown enormously during the last two generations, and these advocates now command a substantial bureaucratic infrastructure. They have already begun to use the regulatory power of the Federal Government to forward their agenda. The New Civics advocates also have prospered by taking advantage of the American public’s trust that people hired to educate their children actually have that object in mind. They abuse that trust by using the anodyne vocabulary of “volunteerism” and “civics” to obscure their radical political agenda. The New Civics advocates are not yet an all-powerful force in higher education—but they are a formidable one, and their strength grows each year. Only concerted, thoroughgoing action can remove them from our colleges and universities.

Readers should be aware that the New Civics movement now extends far beyond college. Project Citizen and similar organizations insert service-learning and the community organizing model into K-12 education,23 and the New Civics advocates insert publicity for progressive causes wherever they can.24 Here we focus on the role of the New Civics in undergraduate education, but we believe that the New Civics must be excised from every part of the American educational system, from kindergarten to graduate school.

This report focuses yet further upon four universities in the two mountain states of Colorado and Wyoming. The University of Colorado, Boulder (CU-Boulder), is a national leader in the New Civics movement. Colorado State University in Fort Collins (CSU), the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley (UNC), and the University of Wyoming in Laramie (UW) retain more of the old focus on civic literacy and volunteerism—but the New Civics vocabulary and bureaucracy frames civics education at these three colleges as much as at CU-Boulder. Moreover, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching has awarded a Community Engagement Classification to both CSU and UNC.25 These large public universities serve a student body that is fairly typical of modern American college students. Our close analysis of these institutions complements our study of the New Civics at the national level by providing an in-depth examination of the decay of traditional civics education and its replacement by the New Civics—not yet the masters of our universities, but a pervasive and rapidly growing presence throughout the heartland of America’s higher education.

This study has 9 national findings:

- Traditional civic literacy is in deep decay in America. Because middle schools and high schools no longer can be relied on to provide students basic civic literacy, the subject has migrated to colleges. But colleges have generally failed to recognize a responsibility to cover the basic content of traditional civics, and have instead substituted programs under the name of civics that bypass instruction in American government and history.

- The New Civics, a movement devoted to progressive activism, has taken over civics education. “Service-learning” and “civic engagement” are the most common labels this movement uses, but it also calls itself global civics, deliberative democracy, intercultural learning, and the like.

- The New Civics movement is national, and it extends far beyond the universities. Each individual college and university now slots its “civic” efforts into a framework that includes federal and state bureaucracies, national nonprofit organizations, and national professional organizations. Any university that affiliates itself with these national organizations also affiliates itself with their progressive political goals.

- The New Civics redefines “civic activity” as “progressive activism.” It aims to advertise progressive causes to students and to use student labor and university resources to support progressive “community” organizations.

- The New Civics redefines “civic activity” as channeling government funds toward progressive nonprofits. The New Civics has worked to divert government funds to progressive causes since its foundation fifty years ago.

- The New Civics redefines “volunteerism” as labor for progressive organizations and administration of the welfare state. The new measures to require “civic engagement” will make this volunteerism compulsory.

- The New Civics replaces traditional liberal arts education with vocational training for community activists. The traditional liberal arts prepared students for leadership in a free society. The New Civics prepares them to administer the welfare state.

- The New Civics also shifts the emphasis of a university education from curricula, drafted by faculty, to “co-curricular activities,” run by non-academic administrators. The New Civics advocates aim to destroy disciplinary instruction and faculty autonomy.

- The New Civics movement aims to take over the entire university. The New Civics advocates want to make “civic engagement” part of every class, every tenure decision, and every extracurricular activity.

This study also has 4 local findings:

- The University of Colorado, Boulder, possesses an extensive New Civics bureaucracy, but only the fragments of a traditional civics education. The New Civics’ main nodes at CU-Boulder are CU Engage (including CU Dialogues, INVST Community Studies, Leadership Studies Minor, Participatory Action Research, Public Achievement, Puksta Scholars, and Student Worker Alliance Program), service-learning classes, and the Residential Academic Programs.

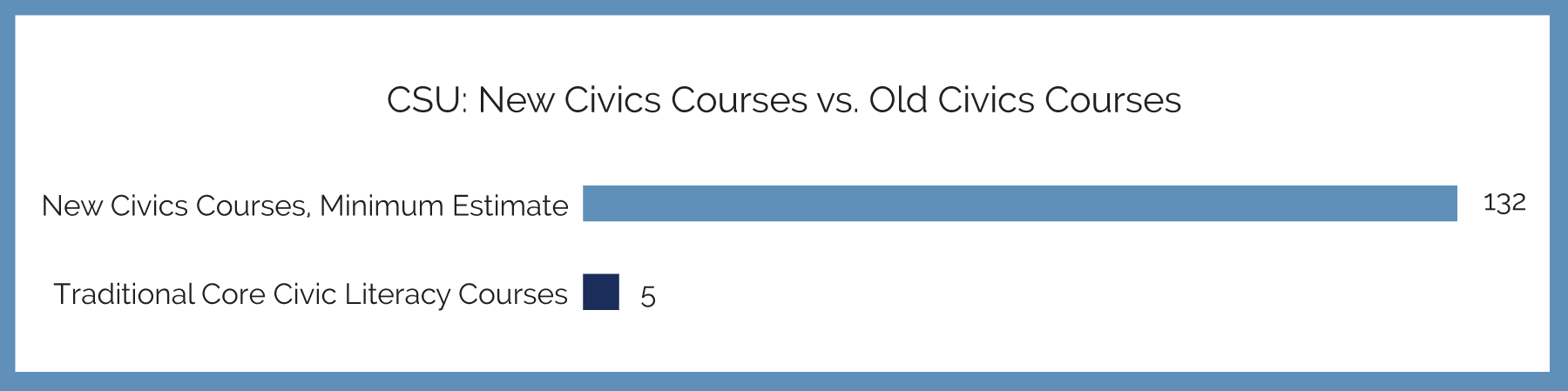

- Colorado State University possesses a moderately extensive New Civics bureaucracy, but only the fragments of a traditional civics education. The New Civics’ main nodes at CSU are Student Leadership, Involvement and Community Engagement (SLiCE), Office for Service-Learning and Volunteer Programs, and the Department of Communication Studies.

- The University of Northern Colorado possesses a moderately extensive New Civics bureaucracy, but only the fragments of a traditional civics education. The New Civics’ main nodes at UNC are The Center for Community and Civic Engagement; the Center for Honors, Scholars and Leadership; the Social Science B.A. – Community Engagement Emphasis; Community Engaged Scholars Symposium; and the Student Activities Office.

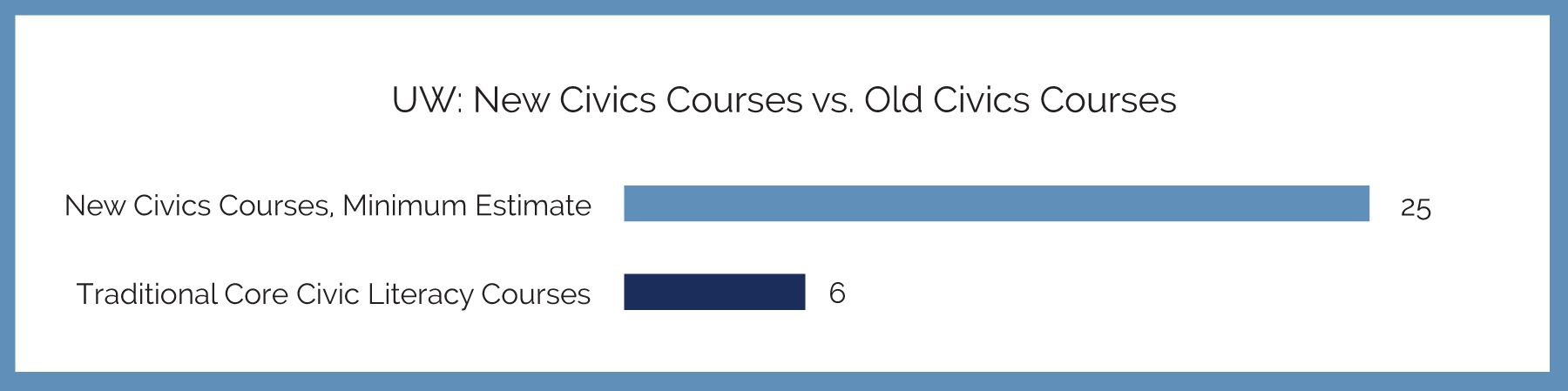

- The University of Wyoming possesses a limited New Civics bureaucracy, and the core of a traditional civics education. The New Civics’ main node at UW is Service, Leadership & Community Engagement (SLCE). UW’s traditional civics education is taught halfheartedly at best, and is in the process of being transformed into a less rigorous distribution requirement.

We make 8 national recommendations:

- Restore a coordinated civic literacy curriculum at both the high school and college levels. Civics education should not start at the college level. When students’ first exposure to civics education comes in college, something has gone wrong with their education at the lower levels. States should design their high school and college civics educations as a coherent whole, and make sure that undergraduate civics education provides more advanced education than high-school civics.