Preface & Acknowledgements

Some years ago, in a conversation with the entrepreneur Arthur Rupe, I proposed that he fund a study of the social justice movement on campus. Because it was a conversation and something of a spur-of-the-moment idea, I didn’t have a plan as to how exactly the National Association of Scholars would go about this study. But Mr. Rupe liked the idea and decided on the spot to fund it.

What lay ahead was a larger challenge than I had imagined. It was as if I had committed to clearing a hundred acres of forest equipped only with a jackknife.

“Social justice” was everywhere in higher education. It was the slogan of student activists, the raison d’etre of many academic programs, the research focus of scholars in many fields, part of the formal mission statements of many colleges, and a phrase that rolled off the tongues of sophomores as the smug answer to virtually any question about public policy. Looking for a definition of the term that fit its ten thousand applications proved futile. “Social justice” may have meant particular things to particular people, but in general it signified only an emotional disposition. The term enunciated a sensibility something like this:

I dislike the United States and American culture. American society treats people unfairly. American culture elevates the wealthy and the privileged over everybody else. It is oppressive. I’m oppressed. I want to change everything. I especially want to change things in the direction of redistributing wealth and privilege. Those should be taken away from the people I don’t like and given to me and the people I do like. The key to making this happen is to raise awareness among those who are oppressed and who don’t necessarily know they are oppressed. Calling for social justice is a way of bringing people together to overthrow the systemic injustices all around us.

This, as I said, is a sensibility, not a definition, but it is a sensibility that can be made to fit with any number of ideological programs. Those who seek to end “gender oppression” find it suits them. Those who seek reparations for slavery and an end to racism find that it suits them as well. Those who fight for open borders, the end of a carbon-based economy, the elimination of meat, the normalization of transgender identity, the end of “broken-windows policing,” the dismantling of the “prison industrial complex,” and the eradication of “Islamophobia” find themselves conforming to this sensibility as well.

The shared sensibility makes it seem to the adherents of these disparate causes that they have more in common than the causes themselves would suggest. Under the banner of “social justice,” they are all fighting what looks like the same enemy. They are the fusion party of all those who are alienated from the traditional American republic. The phrase in the Pledge of Allegiance, “one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all,” sounds like a bitter lie to the adherents of the social justice alliance. “One nation?” No, we are two nations: one for the super-rich and one for the people the rich exploit. “Liberty?” No, we live in fear of men/cops/corporations/fossil fuels/white nationalists, etc. “Justice for all?” Ha, so-called “justice” is privileged people taking care of each other, while ordinary people are kicked to the curb.

It takes very little time on a college campus to discover ideas and attitudes like this in wide circulation. Perhaps only a vocal minority of students and faculty members adhere openly and forcefully to this worldview, but nearly everyone has heard it expressed. Students hear it from one another as well as from their more progressive teachers. More than that, it has settled on campuses as a general atmosphere. When someone says “social justice,” he need not spell out the underlying propositions. The ideas and the temperament are taken for granted. By contrast, any critique of the social justice ideology will be familiar to hardly any students and very few faculty members

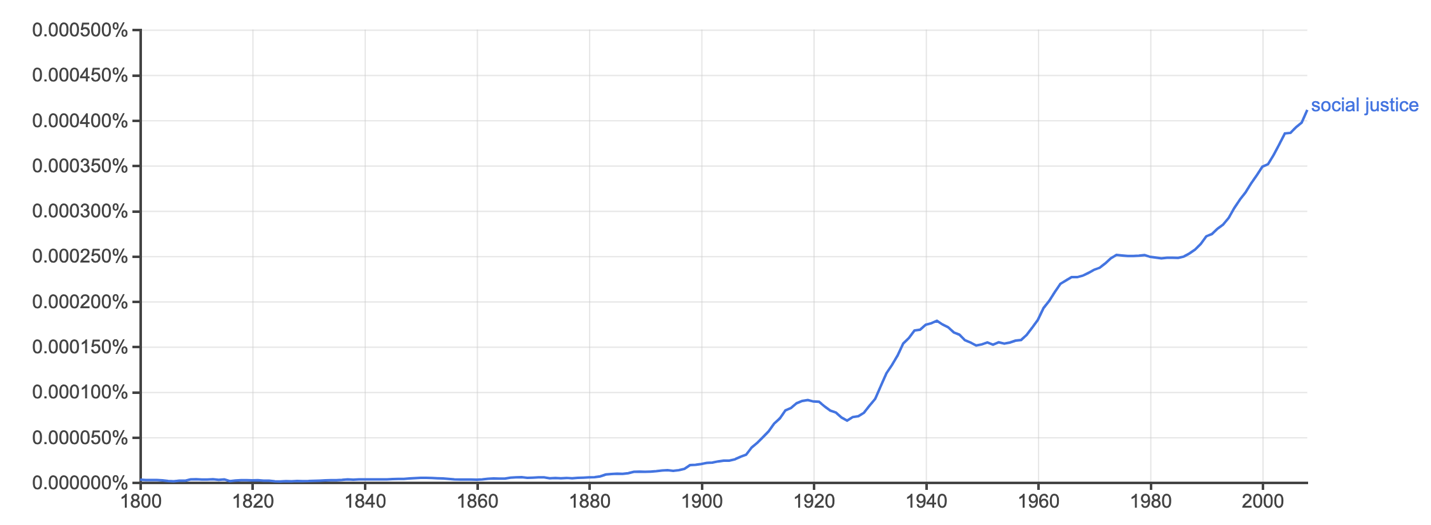

Usage of “Social Justice” from 1800 to 20081

It is not that such critiques are scarce. The Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek wrote one of the most famous critiques, The Mirage of Social Justice (1976). Hayek is often quoted explaining that “Justice is an attribute of individual action. I can be just or unjust toward my fellow man.” But, according to Hayek, “social justice” is a “meaningless conception.” American libertarians and free market economists have built a library full of Hayek-inspired debunkings of social justice claims. Such efforts have not gone unanswered. The high-end of social justice philosophizing includes rebuttals of Hayek and other efforts to rescue the concept from the triviality. A Swiss Catholic writer, Father Martin Rhonheimer, for example, argues:

Hayek’s dismissal of the concept of ‘social justice’ is well-known. While we can basically agree with Hayek’s critique, we should not entirely reject this concept, although it is often used in a vague and emotional way—‘social justice talk.’ Drawing on the tradition of classical liberalism and Catholic social teaching, the true meaning of social justice applies to the basic legal and institutional framework of a society rather than the distributional outcomes of market processes. Therefore, while confirming Hayek’s main points, I will try to show that the concept of ‘social justice’ need not be entirely rejected or even relegated to the category of ‘nonsense,’ as Hayek claims.2

These intellectual debates may be important in their own right, but they are not the subject of this NAS study. Rather, we have set out to capture the pervasiveness of “social justice” rhetoric and its embedded concept in contemporary American higher education. That it took us the better part of a decade to accomplish this testifies to the vast, disorganized mass of material we had to digest. Between our first efforts to start clearing those acres of forest with our jackknife and the publication of this report, we began and completed more than twenty other studies, some of them hundreds of pages long. Many of those studies—including What Does Bowdoin Teach? (2013), Sustainability (2015), Inside Divestment (2015), Making Citizens (2017), and Neo-Segregation at Yale (2019)—deal with “social justice” on campus as a prominent theme.

But finding a path that would allow us to present a portrait of the campus social justice movement as a whole proved difficult indeed. I am grateful to the author of this study, David Randall, who stepped in after many others had sunk in the quicksand. He found his footing with the subject by putting aside the long historical background to the concept and providing what we anthropologists call a “synchronic” account, i.e., a portrait of a culture as it exists within one long moment. This report offers a detailed account of “social justice” as it is on campus today, never mind what it looked like in the 1960s, the 1990s, or the day before yesterday.

To digest the material, David broke it into functional categories, such as the curriculum, mission statements, and accreditation. And to achieve reasonable compression he focused on a limited number of representative colleges and universities. These steps make the report readable—readable at least to those who can bear a surfeit of absurdities piled on mountains of head-shaking folly, rising from dismal plains of ignorance. David to his credit has written the report in the spirit of scrupulously factual ethnography. My characterization of what he reports on is mine alone. The reader who comes to the report as an enthusiast for the social justice cause may read it as a progress report and take satisfaction in how far that cause has advanced. Skeptics such as I, however, will see here a picture of American higher education deep in cultural and intellectual decline.

I can accept that there may be a useful way to define “social justice” as a way to distinguish between the injustices that individuals inflict on one another and the injustices carried out by groups against other groups. The dismantling of the core curriculum in the name of multiculturalism, for example, might count as an act of “social injustice.” That dismantling deprives whole generations of students from receiving the benefits of a cogent education founded on good principles. It was carried out not so much by individuals as by a class of faculty members and administrators in conjunction with activist students who collectively sought such an outcome. They aimed to marginalize from the curriculum the American Founding, the concept of Western Civilization, and an approach to learning that emphasized a shared intellectual and cultural heritage.

Harms inflicted on whole categories of people by organized movements count, I think, as instances of social injustice, and under that rubric, I would place slavery, genocide, abortion, and a perhaps quite a few other ways we have of subjecting the innocent to abuses of power.

This is to say that I am not a Hayekian who dismisses social justice as a “meaningless conception.” But American higher education these days seems to be working hard to prove Hayek right by using the label promiscuously.

I trust that the NAS report will serve as gentle pressure on the public to think twice before adopting this fashionable term. When you say “social justice” do you mean what you say? Would the word “justice” plain and simple serve you better? Do you really wish to put yourself in the company of those who deploy this term as short-hand for their generalized alienation from the rule of law and the enjoyment of liberty among their fellow citizens?

These are the questions implicit in the report. I’m grateful for the opportunity at long last to present them to the public and to Arthur Rupe, who, at age 102, has waited patiently for the results of this inquiry.

I’d also like to thank several anonymous donors for their support, as well as the readers of early drafts of the report. These readers include Robert Maranto, Keith Whitaker, and Mark Bauerlein: they greatly improved this report, though none of its faults are theirs.

Peter W. Wood

President

National Association of Scholars

Precis

In the last twenty years a body of “social justice educators” has come to power in American higher education. These professors and administrators are transforming higher education into advocacy for progressive politics. They also work to reserve higher education jobs for social justice advocates, and to train more social justice advocates for careers in nonprofit organizations, K–12 education, and social work. Social Justice Education in America draws upon a close examination of 60 colleges and universities to show how social justice educators have taken over higher education. The report includes recommendations on how to prevent colleges and universities from substituting activism for learning.

Executive Summary

American universities have drifted from the political center for fifty years and more. By now scarcely any conservatives or moderates remain, and most of them are approaching retirement. The radical establishment triumphed on campus a generation ago. What they have created since is an even more disturbing successor to the progressive academy of the 1990s. In the last twenty years, a generation of academics and administrators has emerged that is no longer satisfied with using the forms of traditional scholarship to teach progressive thought. This new generation seeks to transform higher education itself into an engine of progressive political advocacy, subjecting students to courses that are nothing more than practical training in progressive activism. This new generation bases its teaching and research on the ideology of social justice.

The concept of social justice originated in nineteenth-century Catholic thought, but it has become secular and progressive in twenty-first-century America. Justice traditionally judges freely chosen individual acts, but social justice judges how far the distribution of economic and social benefits among social groups departs from how they “ought” to be distributed. Practically, social justice also justifies the exercise of the state’s coercive power to distribute “fairly” goods that include education, employment, housing, income, health care, leisure, a pleasant environment, political power, property, social recognition, and wealth.

What we may call radical social justice theory, which dominates higher education, adds to broader social justice theory the belief that society is divided into social identity groups defined by categories such as class, race, and gender; that any “unfair distribution” of goods among these groups is oppression; and that oppression can only—and must—be removed by a coalition of “marginalized” identity groups working to radically transform politics, society, and culture to eliminate privilege.

A rough, incomplete catalogue of the social justice movement’s political goals includes increased federal and state taxation; increased minimum wage; increased environmental regulation; increased government health care spending and regulation; restrictions on free speech; restrictions on due process protections; maximizing the number of legislative districts that will elect racial minorities; support for the Black Lives Matter movement; mass release of criminals from prison; decriminalizing drugs; ending enforcement of our immigration laws; amnesty for illegal aliens; open borders; race and sex preferences in education and employment; persecution of conscientious objectors to homosexuality; advocacy for “transgender rights”; support for the anti-Israeli Boycott, Divest, and Sanction movement; avowal of a right to abortion; and mob violence to enforce the social justice policy agenda.

Social justice advocates’ emphasis on words such as justice, equity, rights, and impact all register social justice’s fundamental goal of acquiring governmental power. Social justice advocates tend to dedicate any activity in which they engage to the effort to achieve the political ends of social justice. Activism is the exemplary means to forward social justice. This word signifies the collective exertion of influence via social justice nonprofit organizations. Activism may take the form of organization-building (staff work, fundraising, membership recruitment), publicity, lobbying, and actions by responsible officials in pursuit of social justice. It may also take the form of “protest”—assembling large numbers of people on the streets to “persuade” responsible officials into executing the preferred policies of social justice advocates. Social justice activism formally eschews violence, but far too many social justice advocates are willing to engage in all “necessary” violence.

Social justice activists in the university are subordinating higher education toward the goal of achieving social justice. Social justice education takes the entire set of social justice beliefs as the predicate for education, in every discipline from accounting to zoology. Social justice education rejects the idea that classes should aim at teaching a subject matter for its own sake, or seek to foster students’ ability to think, judge, and write as independent goods. Social justice education instead aims directly at creating effective social justice activists, ideally engaged during class in such activism. Social justice education transforms the very definitions of academic disciplines—first to permit the substitution of social justice activism for intellectual endeavor, and then to require it.

Social justice educators define education as the practice of social justice activism. Experiential learning, which is vocational training in social justice activism, is the heart of social justice education. Other prominent elements include action learning, action research, action science, advocacy-oriented research, classroom action research, collaborative inquiry, community research, critical action research, emancipatory research, participatory action research, and social justice research.

Most colleges and universities today operate under tight fiscal constraints, which lead to dwindling numbers of tenure-track faculty jobs and allow expanding numbers of administrative jobs. These constraints shape the means by which social justice educators extend their influence. They focus on four broad strategic initiatives: 1) the alteration of university and department mission statements; 2) the seizure of internal graduation requirements; 3) the capture of disciplines or creation of pseudo-disciplines; and 4) the capture of the university administration.

The first strategic initiative, alteration of mission statements, provides a wedge by which to pursue the latter three. Social justice educators pursue these other three initiatives with the practical goal to reserve as many jobs as possible for social justice advocates, particularly in higher education, K–12 education, and social work. The capture of the university administration, above all, gives social justice advocates a career track and the expectation of lifetime employment. Social justice advocates want to reserve for themselves all of the ca. 1.5 million American jobs for postsecondary teachers and administrators.

Social justice advocates’ first goal is to incorporate social justice, or related words, into college and university mission statements. This social justice vocabulary sometimes serves as hollow words to fob off social justice advocates. Yet it also works as a promissory note for more detailed changes to impose social justice education. A social justice mission statement generally indicates that a higher education institute no longer really aims to educate students. It really aims at social justice activism, and it will only provide education that doesn’t conflict with social justice ideology. The ideal of social justice does not complement the ideal of education. The ideal of social justice replaces the ideal of education.

The ideal of social justice does not complement the ideal of education. The ideal of social justice replaces the ideal of education.

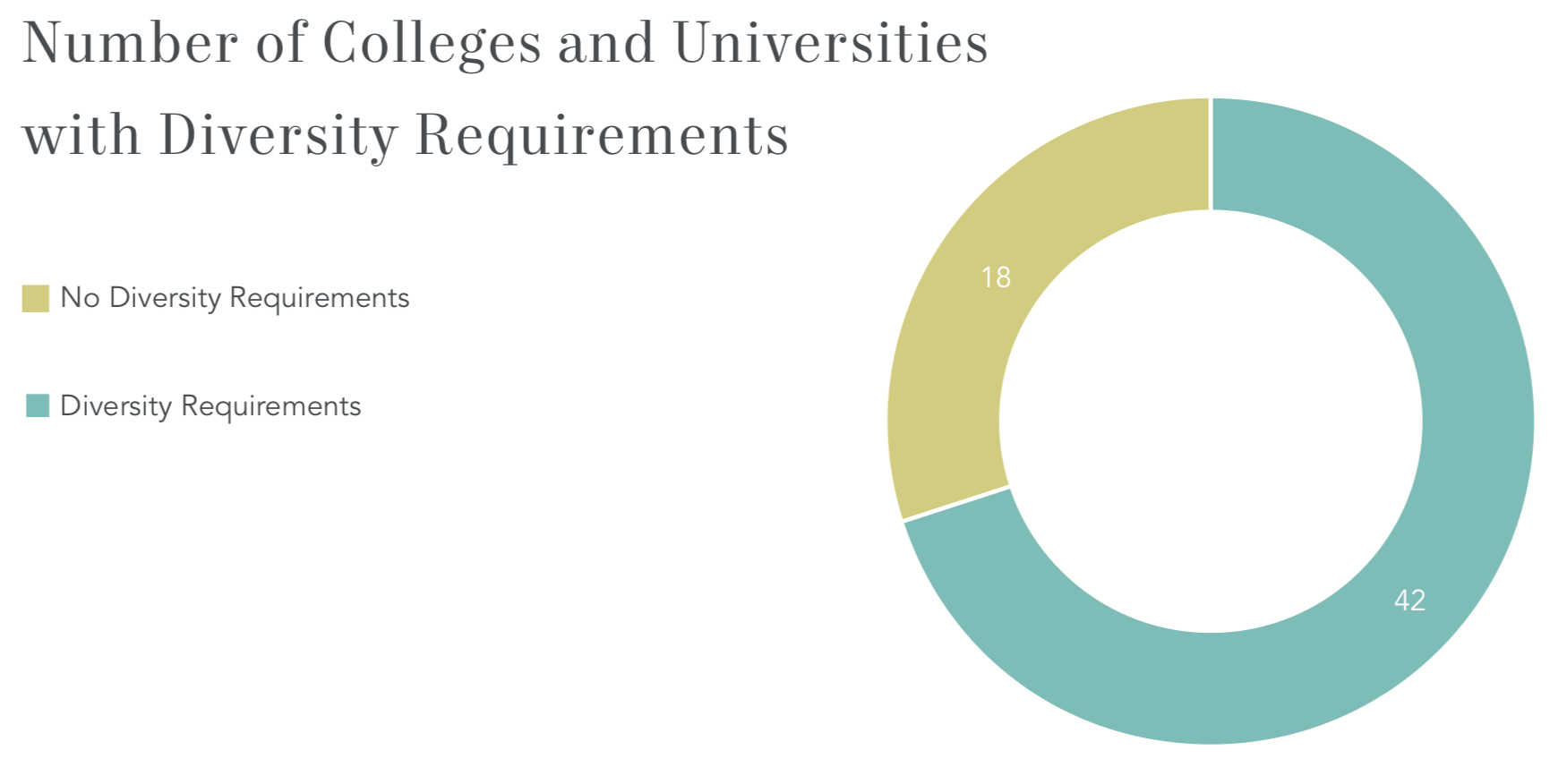

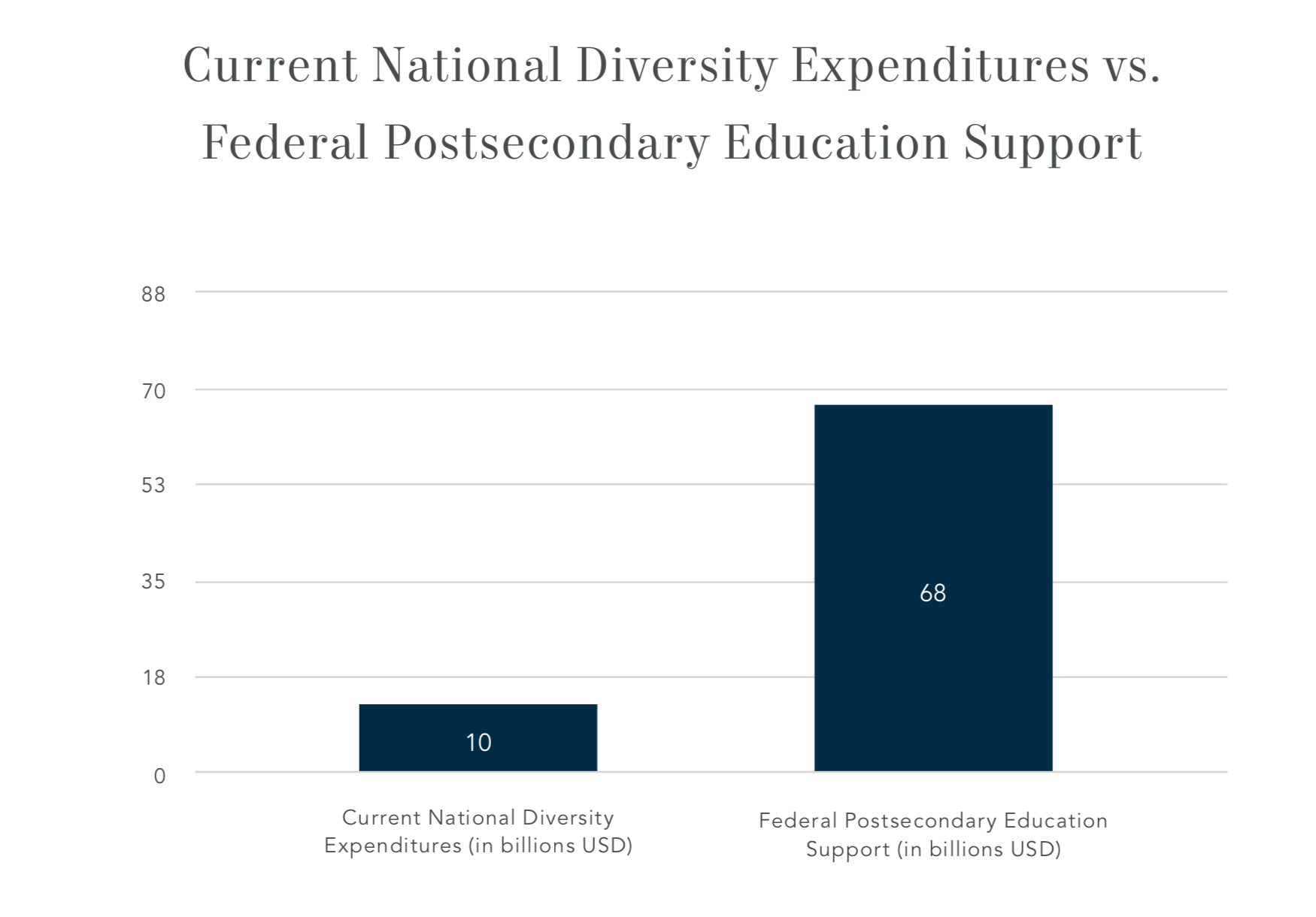

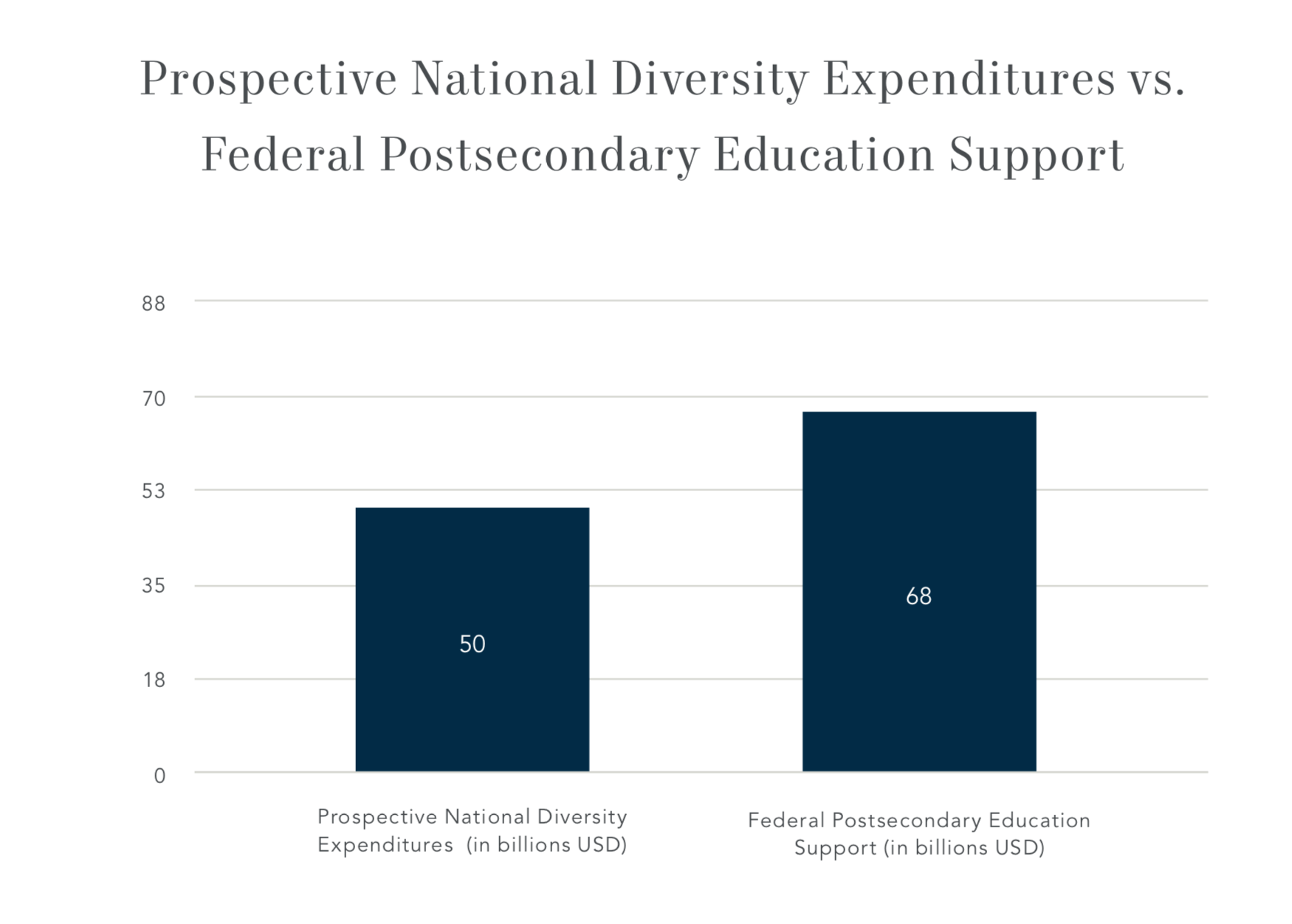

Social justice advocates’ most important curricular tactic within higher education is to insert one or more social justice requirements into the general education requirements. They give these requirements different names, including Diversity, Experiential Learning, Sustainability, Global Studies, and, forthrightly, Social Justice. This tactic forces all college students to take at least one social justice course, and thereby maximizes the effect of social justice propaganda. The common practice of double counting a social justice requirement so that it also satisfies another requirement powerfully reinforces the effect of social justice requirements. These requirements also effectively reserve a large number of teaching jobs and tenure-track lines for social justice educators. No one but a social justice advocate, after all, is really qualified to teach a course in social justice advocacy. The direct financial burden of social justice general education requirements is at least $10 billion a year nationwide, and rising fast.

The direct financial burden of social justice general education requirements is at least $10 billion a year nationwide, and rising fast.

Social justice advocates also have taken over or created a substantial portion of the academic departments in our universities. The departments most likely to advertise their commitment to social justice are those most central to the social justice educators’ ideological vision, political goals, and ambition for employment. The heaviest concentrations of social justice departments are the Identity Group Studies, Gender Studies, Peace Studies, and Sustainability Studies pseudo-disciplines; the career track departments of Education, Social Work, and Criminology; and the departments dedicated to activism such as Civic Engagement, Leadership, and Social Justice. Social justice takes over departments by incorporating social justice into their mission statements, inserting departmental requirements for social justice education, and dedicating as many elective courses as possible to social justice education. When social justice educators control departments entirely, they rapidly shift the definition of that discipline so that it requires social justice education. These changes make it practically impossible to study that discipline without embracing social justice.

Social justice departments denominate their vocational training in activism as experiential learning—or related terms such as civic engagement, community engagement, fieldwork, internships, practica, and service-learning. Service-learning usually refers to relatively unpoliticized experiential learning, which habituates students to the basic forms and techniques of activism, while civic engagement usually refers to more avowedly political social justice activism. The term experiential learning disguises what is essentially vocational training in progressive activism by pretending that it is no different from an internship with an engineering firm. Many supposedly academic social justice courses also focus on readying students for experiential learning courses—and for a further career in social justice activism. Experiential learning courses are what particularly distinguishes social justice education from its progressive forebears. Experiential learning courses, dedicated outright to progressive activism, drop all pretense that teachers and students are engaged in the search for knowledge. Experiential learning is both a camouflaging euphemism and a marker of social justice education.

While social justice education has made great strides among university professors, its dizziest success has been its takeover of the university administration. Higher education administration is now even more liberal than the professoriate. The training of higher education administrators, especially within the labyrinth of “co-curricular” bureaucracies, increasingly makes commitment to social justice an explicit or an implicit requirement. These administrators insert themselves into all aspects of student life, both outside and inside the classroom. Overwhelmingly, they exercise their power to promote social justice. Social justice administrators catechize students in social justice propaganda; select social justice advocates as outside speakers; funnel students to off-campus social justice organizations that benefit from free student labor; and provide jobs and money for social justice cadres among the student body. The formation of social justice bureaucracies also serves as an administrative stepping stone to the creation of social justice departments. Perhaps most importantly, university administration provides a career for students specializing in social justice advocacy.

Higher education’s administrative bloat has facilitated the growth of social justice bureaucracies—among them, Offices of Diversity and Multicultural Affairs; Title IX coordinators; Offices of First-Year Experience and Community Engagement; Offices of Student Life and Residential Life; Offices of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement; Offices of Equity and Inclusion; Offices of Sustainability and Social Justice; and miscellaneous institutes and centers. These bureaucracies focus on co-curricular activities, which consist largely of social justice activities such as Intersectionality Workshops and Social Justice Weekend Retreats. Social justice administrators aim to subordinate the curriculum to the co-curriculum, as the practical way to subordinate the pursuit of truth to social justice advocacy.

Social justice administrators have set up institutions that make social justice advocacy inescapable. Offices of Residential Life have turned large amounts of housing into venues for social justice advocacy. The most intensive advocacy proceeds through Living Learning Communities—housing units dedicated to themes such as Global Citizenship, Gender and Social Justice, and Social Justice Action. Bias Incident Response Teams, which rely on voluntary informers (“active bystanders”) throughout campus, dedicate themselves to gathering reports of “bias incidents”—which, practically speaking, can include any word or action that offends social justice advocates. Bias Incident Response Teams act as enforcers of social justice orthodoxy on campus. Break and Study Abroad programs have also been largely taken over by social justice advocates, and are now frequently exercises in service-learning and social justice advocacy. Offices of Residential Life subject students to social justice education even while they are eating and sleeping, Bias Incident Response Teams monitor every private social interaction, and Study Abroad and Break programs subject students to social justice education even while they are away from campus.

The social justice bureaucracies sponsor a large number of social justice events on campus. These events are the actual substance of social justice education on campus. The varieties of social justice events include activism programs, commencements, community mobilizations, conferences, dialogues, festivities, films, fine arts performances, hunger banquets,3 lectures, projects, residence hall programs, resource fairs, retreats, roundtables, student education, student training, workshops, and youth activities. The subjects of these events have included activism, ally education, Black Lives Matter, civic engagement, community organizing, diversity, food, gender identity, health care, illegal aliens, implicit bias, leadership, LGBTQ, mental illness, policing, power, prisons, racial identity, social justice, and sustainability.

The social justice bureaucracies also engage in large amounts of student training. This student training identifies, catechizes, and provides work experience for the next generation of social justice advocates. This student training is especially useful for training the next generation of social justice educators. By scholarships, the provision of student jobs, and linking social justice cadres to careers, social justice educators ensure that social justice education is linked to social justice jobs for graduates. The Diversity Peer Educator of today is the Dean of Diversity of tomorrow. Today’s Social Justice Scholar will become tomorrow’s Dean of Student Affairs. Student training provides the cadres for social justice activism.

The Diversity Peer Educator of today is the Dean of Diversity of tomorrow. Today’s Social Justice Scholar will become tomorrow’s Dean of Student Affairs.

Social justice education, in addition, prepares students for positions in private industry (human resources, diversity associates), progressive nonprofit organizations, progressive political campaigns, progressive officials’ offices, government bureaucracies, K-12 education, social work, court personnel, and the professoriate. University administration and faculty directly provide a massive source of employment for social justice advocates: the total number of social justice advocates employed in higher education must be well above 100,000.4 Soon all of higher education may be reserved for social justice advocates, since university job advertisements have begun explicitly to require affirmations of diversity and social justice. These ideological loyalty oaths will effectively reserve higher education employment to the 8% of Americans who are progressive activists.5

Since social justice educators have to publish a minimum amount of peer-reviewed academic research to receive tenure, they have also created an apparatus of journal and book publication as cargo-cult scholarship—an imitation of the form of academic research, largely consisting of after-action reports on social justice activism on campus. The core of this cargo-cult apparatus is a network of hundreds of academic journals dedicated to social justice scholarship, whose editors and peer reviewers are also social justice educators. Their specializations mirror the range of social justice education—ethnic studies and gender studies, education journals and sustainability journals, journals devoted to critical studies, dialogue, diversity, equity, experiential education, inclusive education, intercultural communication, multicultural education, peace, service-learning, social inclusion—and, of course, social justice.

The bureaucracy of accreditation plays an important role in forwarding social justice advocacy at America’s colleges and universities. Some accreditation bureaucracies require diversity, or other keywords that can be used to justify the creation of social justice requirements, programs, or assessments. Where accreditation bureaucracies do not explicitly require social justice advocacy, college bureaucrats often justify social justice advocacy as a way to fulfill other accreditation requirements. In both cases, social justice advocates within colleges and universities twist accreditation to advance their own agenda.

Education reformers must disrupt higher education’s ability to provide stable careers for social justice advocates. These reforms cannot be aimed piecemeal at individual campuses. Social justice education is a national initiative, which has taken over entire disciplines and professions. Social justice’s capture of higher education must be opposed on a similarly national scale. Above all, the opposition must aim at cutting off the national sources of funding for social justice education. A priority should be to deny public tax dollars for social justice education.

Nine general reforms would severely disrupt social justice education:

- eliminate experiential learning courses;

- remove social justice education from undergraduate general education requirements;

- remove social justice education from introductory college courses;

- remove social justice requirements from departments that provide employment credentials;

- remove social justice positions from higher education administration;

- restrict the power of social justice advocates in higher education administration;

- eliminate the “co-curriculum”;

- remove social justice requirements from higher education job advertisements; and

- remove social justice criteria from accreditation.

Most importantly of all, college students must cease cooperating with social justice requirements. A mass, coordinated campaign of civil disobedience, in which students simply stop taking social justice classes, attending social justice events, or obeying social justice administrators, would deal a body-blow to social justice education.

A mass, coordinated campaign of civil disobedience, in which students simply stop taking social justice classes, attending social justice events, or obeying social justice administrators, would deal a body-blow to social justice education.

Report Structure

Prologue. San Francisco State University’s web of social justice advocacy illustrates how the nationwide movement to subsume higher education to the pursuit of progressive political activism operates in one institution.

Introduction. Social justice theory subordinates all endeavors to the pursuit of political activism to enact social justice’s political goals. Radical social justice advocates have established themselves in higher education, and now seek to subordinate all aspects of higher education to the pursuit of social justice. The Four Strategic Initiatives of social justice educators are

- the alteration of university mission statements;

- the seizure of internal graduation requirements;

- the capture of disciplines or creation of pseudo-disciplines; and

- the capture of the university administration.

Social justice advocates have established themselves throughout the 60 colleges and universities we have examined, and have succeeded alarmingly well at their goals.

Mission Statements. University and department mission statements act as promissory notes for future social justice initiatives, and register the fundamental abandonment of education as a goal of these universities and departments.

General Education Requirements. Social justice advocates have inserted requirements that students take courses in areas such as diversity, experiential learning, and social justice, and also erected a system of multiple requirements and double-counted courses that steer students to take social justice courses to fulfill other general education requirements. Social justice advocates capture immense numbers of tenure lines and tuition by requiring students to take social justice courses.

Departments. Social justice advocates have seized or created large numbers of disciplines explicitly dedicated to social justice activism. The heaviest penetration of social justice advocacy is in Identity Group Studies; American Studies; Gender Studies; Sustainability; Global, Human Rights, and Peace Studies; Health Policy and Urban Studies; Law, Political Science, and Public Policy; Education; Social Work; Criminology; Psychology and Sociology; Civic Engagement; Leadership; and Social Justice. These disciplines select and form social justice advocates by a combination of mission statements, requirements, and electives. Social justice has penetrated so far into the departments that it now has colonized writing instruction and even mathematics. Every university we studied has its complement of notable social justice courses.

Experiential Learning. Social justice educators use experiential learning to provide vocational training in progressive activism. The presence of experiential learning courses signals that social justice educators have taken over a department. A representative catalogue of experiential learning courses registers the disciplinary range and the ambitions of social justice education.

University Administration. Social justice advocates have taken over much of university administration, particularly those offices devoted to the “co-curriculum.” They have also taken over the education of higher education administrators, and their professional organizations, and redefined their professional goals as the advancement of social justice.

Social Justice Bureaucracies. Bureaucracies taken over by social justice advocates include Offices of Student Affairs, Offices of First-Year Experience, Offices of Community Engagement, Offices of Social Justice, Offices of Sustainability, Offices of Equity and Inclusion, Offices of Diversity and Multicultural Affairs, Miscellaneous Institutes and Centers, and Title IX Offices. For each of these bureaucracies, we list the number of institutions that possess that office, their varieties of sponsored social justice commitments, the language of sample social justice commitments, and their social justice vocabulary keywords.

Pervasive Social Justice. Social justice advocates make sure there is no escape from social justice advocacy. Social justice now affects where students live and sleep, by way of Offices of Residential Life and Living Learning Communities. Social justice organizes voluntary informers to enforce social justice advocacy in all private life, by way of Bias Incident Response Teams. Break and Study Abroad programs ensure that students remain yoked to social justice even in off-campus academic programs. For each of these bureaucracies, we also list the number of institutions that possess that office, their varieties of sponsored social justice commitments, the language of sample social justice commitments, and their social justice vocabulary keywords.

Social Justice Events. Individual events make up the fabric of campus life. A sample of social justice events gives a sense of the variety of means by which social justice education operates. We list the number of institutions whose events included explicit social justice commitments, their varieties of social justice commitments, the subjects of social justice activism, the language of sample social justice commitments, and their social justice vocabulary keywords.

Student Training. Student training identifies, catechizes, and provides work experience for the next generation of social justice advocates. This student training is especially useful for training the next generation of social justice educators. We list the number of institutions whose student training included explicit social justice commitments, their varieties of social justice commitments, the language of sample social justice commitments, and their social justice vocabulary keywords.

Social Justice Jobs. Social justice education prepares students for positions in private industry, progressive nonprofit organizations, progressive political campaigns, government bureaucracies, K–12 education, social work, criminal justice, and the professoriate by way of graduate school. Higher education administration directly employs massive numbers of social justice advocates. Social justice job requirements, such as diversity statements, ensure that only social justice advocates will qualify for positions in higher education. We list extracts of social justice requirements from several institutions’ job advertisements. We also list a sample of the variety of jobs reserved for social justice advocates.

Journals. Hundreds of academic journals publish social justice pseudo-scholarship, frequently consisting of after-action reports on social justice activism on campus that act as how-to guides for other social justice educators. These publications allow social justice educators to pretend to outsiders that they are engaged in academic research. We list a sampling of 250 academic journals largely or exclusively devoted to social justice education, to illustrate the range of pseudo-disciplines that rely on this pretense of scholarship.

Accreditation. The bureaucracy of accreditation plays an important role in forwarding social justice advocacy at America’s colleges and universities. We briefly survey the criteria used by the six major regional accreditors to forward social justice, and then examine how a sample university in each accrediting region uses accreditation to assess and make more effective its own social justice initiatives.

Conclusion. Higher education reform must disrupt higher education’s ability to provide stable careers for social justice advocates. We recommend Nine General Reforms:

- eliminate experiential learning courses;

- remove social justice education from undergraduate general education requirements;

- remove social justice education from introductory college courses;

- remove social justice requirements from departments that provide employment credentials;

- remove social justice positions from higher education administration;

- restrict the power of social justice advocates in higher education administration;

- eliminate the “co-curriculum”;

- remove social justice requirements from higher education job advertisements; and

- remove social justice criteria from accreditation.

These reforms should come at the federal level and the state level. Moreover, students should cease cooperating with social justice regulations.

Charts. The substantiating data for this report is contained in twenty charts. These charts appear in the PDF version of the report, available online, but not in the print version.

Prologue: If You Come to San Francisco

San Francisco State University (SFSU) emphatically proclaims in its mission statement its “unwavering commitment to social justice,” and its intention to prepare “its students to become productive, ethical, active citizens with a global perspective.”6 And SFSU has succeeded to a remarkable extent. Social justice indoctrination is more pervasive at SFSU than in virtually any other college in the country. San Francisco State University is a model for how social justice advocates are taking over American higher education.

What does that mean?

SFSU defines social justice as practically synonymous with progressive political activism. Its Equity & Community Inclusion bureaucracy cites “non-profit national organizations [that] are committed to social justice advocacy” that include bastions of progressive advocacy such as the Council on American-Islamic Relations, the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the Transgender Law Center.7 SFSU professor Rabab Abdulhadi, College of Ethnic Studies, interprets “social justice” to mean radical anti-Zionism and support of the Boycott, Divest, and Sanction (BDS) movement: “I consider the statement from … President Wong, welcoming Zionists to campus, equating Jewishness with Zionism, and giving Hillel ownership of campus Jewishness, to be a declaration of war against Arabs, Muslims, Palestinians and all those who are committed to an indivisible sense of social justice on and off campus.”8

SFSU’s commitment to social justice is a commitment to progressive political activism—and SFSU has given that commitment detailed administrative backing in every aspect of campus academics and life.

SFSU’s commitment to social justice is a commitment to progressive political activism—and SFSU has given that commitment detailed administrative backing in every aspect of campus academics and life.

SFSU’s commitment to social justice has distorted its general education requirements. SFSU imposes a complex series of general education requirements, which restricts student choice for at least 17 courses.9 Every single requirement can be satisfied by a course devoted to social justice. RRS 276 Race, Activism and Climate Justice satisfies the Life Science (Area B2) requirement, AFRS 260 Power, Racism, and Africana Liberation satisfies the Social Sciences (Area D) requirement, and H ED 120 Educational Justice, Health Equity, and Academic Success satisfies the Humanities (Area C2) requirement.10

SFSU uses the general education requirements system to carve loopholes into government mandates. California state law requires public universities to teach a course in U.S. history and government. SFSU lets students satisfy that requirement with courses such as AIS 103 Introduction to Pacific Studies, AIS 205 American Indians and U.S. Laws, and WGS 150 Women and Gender in U.S. History and Society.11

SFSU imposes four distinct social justice course requirements. Students must take a course apiece in American Ethnic and Racial Minorities, Environmental Sustainability, Global Perspectives, and Social Justice. Students satisfy these requirements with courses such as SOC 410 Grassroots Organizing for Change in Communities of Color, AFRS 256 Hip Hop Workshop, WGS 440 Native Sexualities and Queer Discourse, and H ED 520 Structural Oppression and Social Foundations of Health.

The Social Justice requirement includes a range of courses that further illustrate the nature of social justice at SFSU—courses such as A U 116 Algebra and Statistics for Social Justice, LS 403 Performance and Pedagogy of the Oppressed for Educators, RRS 375 Queer Arabs in the U.S., TPW 490 Grant Writing, and WGS 220 Introduction to Feminist Disability Studies.12

A growing number of SFSU departments and concentrations explicitly dedicate themselves to social justice. These include the Critical Social Thought Program; Education: Concentration in Equity and Social Justice in Education; Education Leadership; Environmental Studies: Environmental Sustainability and Social Justice Emphasis; Global Peace, Human Rights, and Justice Studies; Health Education; LGBT Studies; Race and Resistance Studies; Sexuality Studies; and Women and Gender Studies. All these academic programs subordinate intellectual inquiry to social justice activism.

SFSU pays professors to teach social justice courses. Among the many courses subsidized by taxpayers are AFRS 466 Black Lives Matter: Race and Social Movements, RRS 201 SFSU’s Palestinian Cultural Mural and the Art of Resistance, and WGS 552 Transgender Identities and Communities.

SFSU’s basic writing instruction now forwards social justice. SFSU’s Communication department, which teaches basic writing, includes the courses COMM 120 Language, Culture, and Power, COMM 304GW Writing About Communication and Masculinities, COMM 348GW Writing About Environmental Rhetoric, COMM 403 Transgender Communication Studies, COMM 503 Gender and Communication, COMM 525 Sexualities and Communication, COMM 542 Dialogues Across Differences, COMM 552 Performance and Feminism, COMM 553 Performance and Identity, and COMM 557 Performance and Pedagogy of the Oppressed for Educators.13

SFSU’s basic mathematics instruction now also forwards social justice. Students who wish to learn mathematics at SFSU can now take A U 116 Algebra and Statistics for Social Justice or A U 117 Statistics for Social Justice. The latter course uses “topics such as education equity, income inequality, racism, and white supremacy and gender inequality to examine data using statistics.”14

SFSU uses Experiential Learning Courses to provide course credit for vocational training in progressive activism. Environmental Studies offers ENVS 530 Environmental Leadership and Organizing and ENVS 570 Applied Local Sustainability; Race and Resistance Studies offers AFRS 694 Community Service Learning; and Women and Gender Studies offers WGS 798 Feminist Internship: Gender and the Nonprofit Industrial Complex.

But SFSU’s commitment to social justice doesn’t stop in the classroom. Very large portions of SFSU’s bureaucracy are also dedicated to social justice.

SFSU’s “co-curricular” bureaucracies work together to orient student activities toward social justice activism. In the Division of Student Life, the Dean of Students distributes an annual Social Justice Award.15 The First-Year Experience bureaucracy’s Course Expectations & Student Learning Outcomes include “Opportunities to discuss social justice, equity, and inclusion.”16 The Institute for Civic and Community Engagement sponsors community service-learning as “a way to strengthen your understanding of social justice.”17 Other SFSU bureaucracies explicitly dedicated to social justice include Equity & Community Inclusion;18 the Office of Diversity & Student Equity,19 and the César E. Chávez Institute.20

Social justice advocates’ capture of the professoriate and the administration ensure that SFSU events forward social justice advocacy. The Constitution Day 2018 program featured talks on subjects including “Social Ontology of Police Violence: Social Groups and Social Institutions,” “How the Second Amendment Reveals White Nationalism,” and “The Future of Whiteness: Dog Whistle Politics or Cross-Racial Solidarity?”21 The 2019 SF State Faculty Retreat invited proposals for talks on subjects such as “How do you infuse social justice into your classroom? How does social justice inform your curriculum? How do students grapple with social justice in their coursework and assignments? How does social justice inform your teaching, service, scholarship, and creative work?”22

SFSU is now crafting its job advertisements to make sure that only social justice advocates will be hired in the future. Ads for both an Assistant Professor of Ancient Greek/Roman Philosophy and a tenure-track position in Linguistics: Sociolinguistics include the stipulation of “Providing curricula that reflect all dimensions of human diversity, and that encourage critical thinking and a commitment to social justice.”23

Throughout San Francisco State University, a web composed of mission statements, general education requirements, departments, bureaucracies, events, and job advertisements forwards “social justice”—a fig leaf for progressive political advocacy. Each individual strand of this web degrades SFSU’s ability to provide a proper education for its students. Jointly, these strands have deformed SFSU as a whole. SFSU is an institution far gone in a terrible metamorphosis—from an institution dedicated to the pursuit of truth to an institution which takes adherence to progressive political beliefs to be the precondition for the pursuit of knowledge, and which is dedicated to the pursuit of progressive political advocacy.

San Francisco State University is a normal American institution of higher education. It’s a bit farther along in its social justice metamorphosis than its peers, but virtually every college and university in America is undergoing the same transformation. A national movement by social justice advocates is transforming all of American higher education into a tool for progressive political advocacy.

This report looks at 60 representative colleges and universities, and demonstrates how each strand of social justice advocacy is a national trend, frequently forwarded by countrywide institutions such as disciplinary and professional organizations, nonprofit organizations, academic journals, and accreditation agencies. It intends to inform the public that any particular example of social justice advocacy in a college is not a one-off, but part of a nationwide campaign. The report’s conclusion is that any attempt to restore our colleges and universities to institutions devoted to the pursuit of truth cannot satisfy itself with reforms within individual institutions. We need a nationwide campaign to oppose the nationwide campaign of the social justice advocates.

We should not forget, however, that social justice education works by a multitude of reinforcing strands within each institution—mission statements, general education requirements, departments, experiential learning courses, bureaucracies, events, job advertisements, and more. The individual portrait of San Francisco State University illustrates how the web of social justice advocacy operates within each institution.

The web gets thicker each year. Keep an eye for news from the Bay Area. Every change SFSU makes to tighten social justice education soon will be standard across the nation.

Remember San Francisco State University as we examine the nationwide movement to subsume higher education to the pursuit of social justice advocacy.

Introduction

Social justice theory subordinates all endeavors to the pursuit of political activism to enact social justice’s political goals. Radical social justice advocates have established themselves in higher education, and now seek to subordinate all aspects of higher education to the pursuit of social justice. The Four Strategic Initiatives of social justice educators are

1. the alteration of university mission statements;

2. the seizure of internal graduation requirements;

3. the capture of disciplines or creation of pseudo-disciplines; and

4. the capture of the university administration.

Social justice advocates have established themselves throughout the 60 colleges and universities we have examined, and have succeeded alarmingly well at their goals.

Academia’s Radical Drift

American universities have drifted from the political center for fifty years and more. As they lost their moorings in the American mainstream they became close-minded. In the 1980s, when the academic mind was still closing, a substantial minority of academics still professed conservative or moderate politics. By now scarcely any conservatives or moderates remain, and most of them are approaching retirement. A large number of university departments have no conservatives at all.24 Ideological pluralism in American academia is effectively dead. Universities almost entirely teach progressive ideas, hire progressive administrators and faculty, and invite progressive speakers to campus. They subject students to courses that are nothing more than practical training in progressive activism.

The radical establishment triumphed on campus a generation ago.25 What they have created since is an even more extreme successor to the progressive academy of the 1990s. In the last twenty years, a generation of academics and administrators has emerged that is no longer satisfied with using the forms of traditional scholarship to teach progressive thought. This new generation seeks to transform higher education itself into an engine of progressive political activism. This new generation bases its teaching and research on the ideology of social justice.

Social Justice Theory

The Concept

The concept of social justice originated in nineteenth-century Catholic thought, received a modern reformulation by way of John Rawls’s Theory of Justice (1971),26 and has become secular and progressive in twenty-first-century America. Justice traditionally judges freely chosen individual acts, but social justice judges how far the distribution of economic and social benefits among social groups departs from how they “ought” to be distributed.27 Lori Molinari of the Heritage Foundation helpfully summarizes how social justice advocates in America describe social justice. They call it the moral obligation for mankind to create “a ‘fair and compassionate’ distribution of goods and burdens within society.” Social justice advocates have an expansive view of the goods that government and society are morally obligated to distribute “fairly.” These goods include “income; employment opportunities; wealth; property ownership; housing; education (including access to relevant technology); access to health care, transportation, and child care services; and personal safety.” Many social justice advocates add to this list “access to political power, political participation, social recognition, recreation or leisure opportunities, and the right to ‘a healthy and pleasant environment.’”28

The self-understanding of social justice advocates can seem quite attractive. Medea Benjamin, co-founder of Code Pink, puts it this way: “Social justice means moving towards a society where all hungry are fed, all sick are cared for, the environment is treasured, and we treat each other with love and compassion.”29 Paul George of the Peninsula Peace and Justice Center says that “Social justice means complete and genuine equality of all people.”30 Rabbi Michael Lerner, co-founder of the Tikkun Community, defines the concept at greater length:

By social justice I mean the creation of a society which treats human beings as embodiments of the sacred, supports them to realize their fullest human potential, and promotes and rewards people to the extent that they are loving and caring, kind and generous, open-hearted and playful, ethically and ecologically sensitive, and tend to respond to the universe with awe, wonder[,] and radical amazement at the grandeur of creation.31

Social justice solely defined as moral aspiration seems unobjectionable.32 As we shall explore at greater length below, the trouble is that social justice theory also justifies the exercise of the state’s coercive power to bring its particular moral aspirations into practice—and that it does not recognize as equally important such rival moral aspirations as individual liberty and the rule of law.33 But if social justice were nothing more than an uncoercive exhortation that every one of us should be our brother’s keeper, there would be nothing about it to raise concern.

Traditional American Propositions

The following list of propositions have had broad-to-overwhelming assent among Americans for most of our nation’s history:

• the free market can distribute economic goods more fairly than the government;

• it is inefficient for the government to redistribute goods;

• it is immoral for the government to redistribute goods;

• it is dangerous to liberty to grant government the power to redistribute goods;

• economic and social goods are not “rights”

• compassionate redistribution of goods should operate through the freely given consent of individual charity rather than the coercive dictates of government;

• the rule of law and procedural fairness are essential goods;

• government should guarantee equality of opportunity, not equality of results;

• individuals are primarily responsible for their own success or failure in private life;

• the individual self, American citizenship, and common humanity are the most important American “identities”

• American citizens have a duty to advance American national interests; and

• America is a republic of free and equal citizens that requires no liberation from “oppression.”

Liberal social justice advocates tend to give these propositions short shrift; radical social justice advocates usually contradict them explicitly. Even the broadest, most anodyne definition of social justice fits awkwardly with the traditional American political consensus.

Unfortunately, social justice is not just uncoercive exhortation. Molinari also emphasizes the important distinction between liberal and radical advocates of social justice. Radicals, unlike liberals, also “tend to view society as fractionalized into various social identity groups (defined by class, race, gender, sexual orientation, ability, etc.) that occupy ‘unequal social locations.”’ These radicals define as oppression “the unjust social processes and relations that have produced and work to perpetuate society’s unfair distribution” of goods and burdens. Radicals believe that oppression can only—and must—be removed by radically transforming “the mechanisms of political participation, workplace decision-making processes, the division of labor, and the overall organization of society, as well as the culture that pervades it.” They also believe that the way to achieve this end is to assemble “coalitions among the various ‘marginalized’ identity groups in order to maximize political influence.”34

| Social Group | Privileged | Oppressed |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Female, Intersexed, Transgendered, Gender Queer |

| Age | Adults (18 – 64) | Children and elders |

| Ability | People without impairment | People with impairment |

| Religion | Christianity | Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Baha’i, Paganism, Taoism, Atheisms, Rastafari, Sikhism, Judaism, Zoroastrian, etc. |

| Ethnicity | European | People of color |

| Social Class | Middle and upper class | Poor and working class |

| Sexual Orientation | Heterosexual | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Two-Spirited, Queer, Questioning |

| Indigenous Culture | Non-Aboriginal | First Nation, Métis, Inuit, Indigenous, Aboriginal |

| National Origin | North American-born | Immigrant or Refugee |

| (First) Language | English | Other than English |

Oppression and Privilege Framework, Stage Left Productions Workshop for Canada World Youth, p. 4, https://acgc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Oppression-and-Privilege-Framework.pdf

The radical advocates of social justice also speak the language of coercion. In 2018, a Social Justice Task Force at SUNY Plattsburgh recommended that “The college develop and disseminate to administration, faculty, and staff its own employee conduct manual … and employ it as part of a comprehensive and compulsory social justice training program for employees and service personnel.”35

Fiction writer and essayist Johnny Townsend, writing in the LA Progressive, says that “Every degree from every accredited college, university, or trade school must include at least one mandatory course on race, gender, and social justice. … My current employer feels it important to address racial and social justice. Every employee is required to participate in an all-day training.”36

Some radical advocates have already gone a considerable distance toward justifying outright violence. In 2019, Dr. Billie Murray, “a rhetorical activist scholar … [who] believes that her research should contribute to social justice and the public good,” gave a lecture at Villanova University meant to “challenge the violence/nonviolence binary that limits our understanding of activist practices. Drawing on examples from her fieldwork with anti-fascist activists, she will argue that we should reimagine activism as combative. Such an expanded understanding will allow us to better discern the efficacy and ethics of combative tactics and how they work in concert with traditional, nonviolent activism.”37 Radical social justice advocates habitually resort to coercive policies to pursue their goals, a growing number use the language of revolution,38 and some such as Dr. Murray are already inching toward the blunt call for violence.

Radical social justice advocates have the upper hand within the national movement as a whole. And social justice in higher education means radical social justice. The introduction to a 2018 Social Justice Summit at the University of Florida provides a good illustration of what social justice means in America’s colleges:

Social justice refers to identifying and understanding social power dynamics and social inequalities that result in some social groups having privilege, power, and access; and others being disadvantaged, oppressed, and denied access. Social justice promotes cross-cultural interactions and demands that all people; regardless of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, social class, gender identity and expression, language, national origin, worldview (religion, spirituality, and other values), physical or mental (dis)ability, or education; have a right to basic human dignity and have their basic needs met. It involves social actors who have a sense of their own agency to make an impact, as well as a sense of social responsibility toward and with others and to society as a whole through engaging in allyship.39 [Punctuation, italics, and bold-face reproduced unchanged.]

The University of Florida defines social justice by invoking identity-group politics and oppression. The social justice the University teaches is the social justice of the radical activists.

Radical social justice theory—which we’ll just call “social justice” from now on, since the radicals dominate higher education—draws heavily on scholarly schools that have grown up around the work of a few notable intellectuals. Key words in social justice vocabulary make this debt clear. Power invokes the writings of Michel Foucault and Saul Alinsky.40 Gender identity and expression draws upon Judith Butler.41 Critical race theory cites Derrick Bell.42 Privilege depends upon the work of Peggy McIntosh.43 Virtually every abstract concept in the University of Florida’s definition of social justice—access, allyship, inequality, needs, social responsibility—draws upon social justice’s theoretical framework instead of the common-sense definitions of the dictionary.44

The Pronoun Wars—the zealous campaign by social justice advocates to replace a fixed he and she with a mutable phantasmagoria of self-proclaimed genders, each with its own pronoun—are another front in social justice advocates’ desire to liberate every individual. In this case, every individual must be liberated from the oppression of language that faithfully reflects immutable biological reality.45

ABC’s of Social Justice: A Glossary of Working Language for Socially Conscious Conversation: Selected Definitions

Department of Inclusion & Multicultural Engagement, Lewis & Clark College

Allyship: an active verb; leveraging personal positions of power and privilege to fight oppression by respecting, working with, and empowering marginalized voices and communities; using one’s own voice to project others’, less represented, voices

Cisgenderism: a socially constructed assumption that everyone’s gender matches their biological sex, and that that is the norm from which all other gender identities deviate

Classism: any attitude or institutional practice which subordinates people of a certain socioeconomic class due to income, occupation, education, and/or their economic status; a system that works to keep certain communities within a set socioeconomic class and prevents social and economic mobility

Disability: being differently abled (physically, mentally, emotionally) from that which society has structured to be the norm in such a way so that the person is unable to move, or has difficulty moving—physically, socially, economically—through life

Discrimination: actions or thoughts, based on conscious or unconscious bias, that favor one group over others

Educate yourself: taking time to learn about issues from other communities for oneself without making people of those communities spend time teaching you. By learning about the histories and experiences of target groups, we can become better allies and advocates.

Gender identity: a person’s individual and subjective sense of their own gender; gender identities exist in a spectrum, and are not just masculine and feminine

Genocide: the intentional attempt to completely erase or destroy a people through structural oppression and/or open acts of physical violence

Nativism: prejudiced thoughts or discriminatory actions that benefit or show preference to individuals born in a territory over those who have migrated into said territory

Privilege: benefit, advantage, or favor granted to individuals and communities by unequal social structures and institutions

Social justice: the practice of allyship and coalition work in order to promote equality, equity, respect, and the assurance of rights within and between communities and social groups

Unconscious bias: negative stereotypes regarding a person or group of people; these biases influence individuals’ thoughts and actions without their conscious knowledge. We all have unconscious biases.

White privilege: the right or advantage provided to people who are considered white; an exemption of social, political, and/or economic burdens placed on non-white people; benefitting from societal structuring that prioritizes white people and whiteness

“ABC’s of Social Justice: A Glossary of Working Language for Socially Conscious Conversation,” Department of Inclusion & Multicultural Engagement, Lewis & Clark College, https://www.lclark.edu/live/files/18474-abcs-of-social-justice.

Political Goals

Social justice’s core claims are a series of abstractions rather than concrete political goals. No one person or institution speaks with recognized authority to define the credo of social justice. The social justice movement has no universally recognized political program.

We must instead cite what large numbers of social justice advocates say social justice requires, and use this to approximate the social justice movement’s actual political agenda. The following political program—which I describe in language that I take to represent the actual, frequently negative effect of these policies—should be taken as a rough, incomplete catalogue of the social justice movement’s political goals:

- increased federal and state taxation;46

- increased minimum wage;47

- increased environmental regulation;48

- increased government health care spending and regulation;49

- restrictions on free speech;50

- restrictions on due process protections;51

- maximizing the number of legislative districts that will elect racial minorities;52

- support for the Black Lives Matters movement;53

- releasing cop-killers from prison;54

- mass release of criminals from prison;55

- decriminalizing drugs;56

- ending enforcement of our immigration laws;57

- amnesty for illegal aliens;58

- open borders;59

- race and sex preferences in education and employment;60

- persecution of conscientious objectors to homosexuality;61

- advocacy for “transgender rights”;62

- support for the anti-Israeli Boycott, Divest, and Sanction movement;63

- avowal of a right to abortion;64 and

- mob violence to enforce the social justice policy agenda.65

The Green New Deal of 2019 also illustrates the political agenda of the social justice movement.66

Political Orientation and Activism

Many social justice keywords derive from the world of the law—not only justice and equity but also advocate and (in its modern sense) diversity. Social justice advocates use justice polemically, but the word also signals their interest in achieving their ends through judges and bureaucrats. Equity likewise builds upon legal equity, that aspect of the legal tradition most open to departing from the letter of the law, so as to leverage judicial power for progressive ends. All rights (as Hannah Arendt noted in The Origins of Totalitarianism) look to the state to enforce them67—as opposed to liberties, which are the birthright of every human being. The multiplication of concepts such as food justice, educational poverty, and health equity elaborate new extensions of state power to tax the citizenry to fund progressive spending priorities. This broad invocation of legal language registers social justice advocates’ ambitions to enact social justice via state power.

San Francisco State University, Equity & Community Inclusion, National Organizations

These non-profit national organizations are committed to social justice advocacy and education and can provide a wide array of opportunities for further learning and exploration. … (Note: SF State does not necessarily endorse or support the views of these organizations. These resources are provided to promote self-learning and critical analysis.)

• American Association for Access, Equity and Diversity

• American Association of People with Disabilities

• American Civil Liberties Union

• Anti-Defamation League

• Campus Pride

• CATALYST

• Center for the Study of Race & Equity in Education

• Council on American-Islamic Relations

• Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund

• Diversity Collegium

• Ford Foundation

• Human Rights Campaign

• Institute for Women’s Policy Research

• LGBT Rehab Centers

• Louis D. Brandeis Center

• Lumina Foundation

• Men Can Stop Rape

• Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund

• National Coalition Building Institute

• National Congress of American Indians

• National LGBTQ Task Force

• National Women’s Law Center

• Southern Poverty Law Center

• The Innocence Project

• The Representation Project

• Transgender Law Center

National Organizations, Resources for Self-Learning, Equity & Community Inclusion, San Francisco State University, https://equity.sfsu.edu/resources.

The corollary to social justice’s political orientation is that social justice advocates seek to dedicate whatever activity in which they engage to the effort to achieve the political ends of social justice. Art should be a mural for Black Lives Matter. Literature should be a novel whose moral is that we should amnesty illegal aliens. At Pomona College, the Introduction to Statistics class now dedicates itself to social justice: “Topics include global poverty, global climate change, environmental rights, death penalty, labor laws, civil rights, access to education, healthcare, water rights, elections, and debt.” The class is “a community partnership class, [where] the final group projects will be conducted in the service of local organizations.”68

Activism is the exemplary means to forward social justice. This word signifies the collective exertion of influence via social justice nonprofit organizations. Activism may take the form of organization-building (staff work, fundraising, membership recruitment), publicity, lobbying, and actions by responsible officials in pursuit of social justice. It may also take the form of “protest”—assembling large numbers of people on the streets to “persuade” responsible officials to execute the preferred policies of social justice advocates, or to fail to execute policies they oppose. Social justice activism formally eschews violence, but the recent string of social-justice riots to suppress free speech argues that, for far too many social justice advocates, achieving social justice by any means necessary practically includes all “necessary” violence.69

The great body of social justice activists in American colleges and universities have been subordinating higher education toward the goal of achieving social justice.

Social Justice Education

Social justice education is taking over ever larger portions of our colleges and universities.70 Social justice education takes the entire set of social justice beliefs as the predicates for education, in every discipline from accounting71 to zoology.72 But the spread of social justice in our campuses does not just mean a radical narrowing of intellectual horizons. It also subordinates all education toward forwarding social justice political activism.

Sustainability’s Social Justice Pillar: The Triple Bottom Line

Social justice education’s sustainability component incorporates scientific disciplines such as environmental science and pre-existing movements such as environmentalism. Sustainability frequently refers to the “triple bottom line”—the need to pursue economy, environment, and equity (or social goals). Equity and social goals euphemize social justice and its political agenda. So at Northwestern University the Sustainability Director cites the Office of Institutional Diversity and the Women’s Center as supporting “the social justice pillar of sustainability”—which includes race preferences and abortion rights. The Sustainability movement’s Social Justice Pillar—its dedication to equity and social goals—distinguishes it from environmentalism.

Social justice education rejects the idea that classes should aim at teaching a subject matter for its own sake, or seek to foster students’ ability to think, judge, and write as independent goods. Social justice education instead aims directly at creating effective social justice activists, ideally engaged during class in such activism. As Shirley Mthethwa-Sommers (Associate Professor in Education, Nazareth College) puts it,

Social justice education theories encourage teachers and students to be actively involved in fighting for social justice and ameliorating discriminatory policies and practices. For example, students are encouraged to investigate social class inequities and work to eliminate them as part of their classroom projects and work. In an English Language Arts classroom for example, the students might examine the Harry Potter series for gender construction and question the roles girls and boys and women and men occupy in the series; they might explore construction and ‘normalization’ of hierarchy based on sexuality and disability; or they might examine the subtext of colorblindness. Through examination of the characters, students might uncover covert ideologies of oppression delineated in the series and participate in writing a letter to either the author or the publisher highlighting their findings and requesting books that affirm everyone. This project meets social justice education criteria by unveiling oppressive structures and practices within a fictional book series and calling for transformation of those structures and practices.73

Social justice education transforms the very definitions of academic disciplines—first to permit the substitution of social justice activism for intellectual endeavor, and then to require it.

Social justice’s general stipulation that theory and practice are inseparable—that the point of thought is to engage in (political) action—forwards social justice education’s shift toward classroom activism. Translated into the world of education, social justice theory, borrowing from older education theorists such as John Dewey74 and Paolo Freire,75 argues that the most effective form of education is learning by doing. The unmodified word effective tacitly mixes up pedagogically effective and politically effective. As Heather Hackman (Founder, Hackman Consulting Group: Deep Diversity, Equity and Social Justice Consulting) puts it, “To be most effective, social justice education requires an examination of systems of power and oppression combined with a prolonged emphasis on social change and student agency in and outside of the classroom.”76 Social justice educators define education as the practice of social justice activism.

Much of social justice education consists of the capture of classes, departments, general education requirements, and entire disciplines. The most notable aspect of this deformation of education is experiential learning—also known by related terms such as service-learning, civic engagement, and community learning.77 Experiential learning justifies itself as an extension of the engineering or the education internship.78 But experiential learning is not just an internship, which is intended to complement classroom learning. Experiential learning substitutes “learning by doing” for classroom learning. At the most practical level, we may measure this substitution by way of colleges’ permitted or required credit hours for experiential learning, and the determination of how many hours of work replace how many hours in the classroom.79

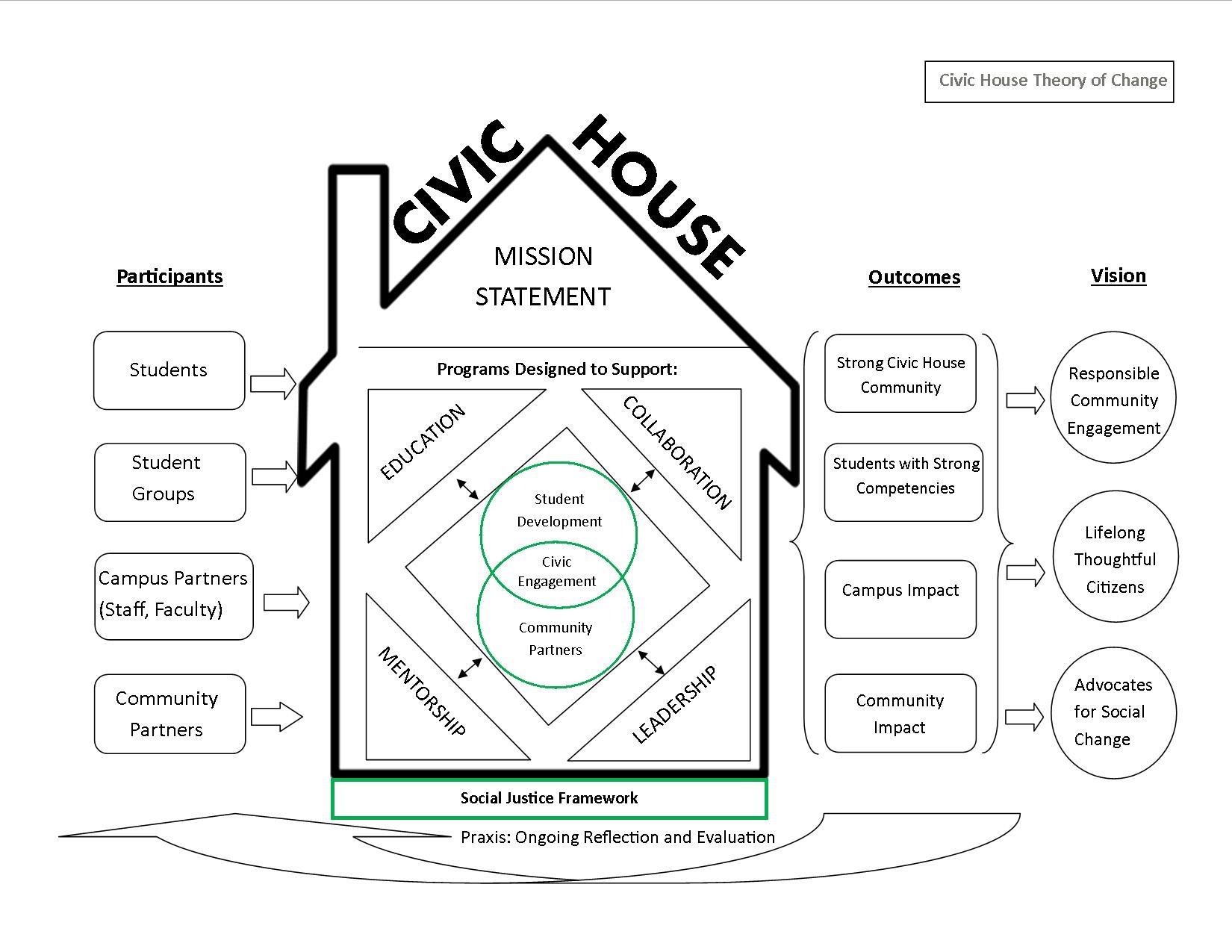

University of Pennsylvania, Civic House Mission Statement, Social Justice Framework

Social Justice Framework and Theory of Change, Civic House, University of Pennsylvania, https://www.vpul.upenn.edu/civichouse/socialjusticeframework.php.

Experiential learning’s substitution of work for study fundamentally undermines the idea of the university as a place dedicated to the disengaged search for truth, where the search for truth precedes action and does not presuppose what that action should be. Spencer Case (Philosophy, University of Colorado Boulder) notes that the assumptions of experiential learning disparage classroom learning: “Presumably, what makes Engaged Philosophy engaged are the students’ service projects. If so, then the implication is that philosophy classes without service projects are disengaged, or at least less fully engaged than those that have them. Engagement with ideas seemingly doesn’t count as genuine engagement.”80 Case also notes that experiential learning’s assumptions, “[t]he anti-theoretical tone of the service-learning movement, implicit even in the rhetoric of moderates,” encourage the increasing displacement of classroom learning. “The slope here really is slippery,” writes Case. “If we accept that even 20 percent of a student’s grades should be service-based—on, say, the grounds that philosophy belongs in the ‘real world’—then the open question will be ‘Why not more?’”81

Experiential learning also accelerates the decline of academic standards. John Kijinski (Professor of English and Emeritus Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, SUNY Fredonia) notes,