Executive Summary

The “Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions” (BDS) movement against Israel is one of the faces of anti-Semitism in the United States.1 It threatens not only Jewish students and scholars but also the political neutrality of the university. The BDS movement is particularly concentrated in higher education and creates an environment of academic politicization to the detriment of academic freedom, freedom of speech, and constructive civil discourse. BDS, similarly, contributes to a hostile campus environment for Jewish students, and supporters of Israel. The BDS movement promotes a one-sided narrative that demonizes the Jewish state while disproportionately amplifying narratives of Palestinian grievance and Arab victimhood.

Anti-Israel student activism is a growing problem that threatens the political neutrality of universities due to widespread connections between pro-BDS student groups and a larger network of progressive and left-wing organizations. Rather than relying on organic student activism designed to foster civil debate, campus BDS groups thrive by means of their connection to well-funded political activism from beyond the university. In some cases, this network of pro-BDS organizations connects to Palestinian terrorism. Spearheaded by campus groups such as Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), campus-based BDS efforts have grown over the past two decades. Anti-Semitism and anti-Israel activism on contemporary American campuses is well-documented. Less understood are the power dynamics of BDS activism on campus, how student activism influences college administrations, and how the campus movement is supported and funded by outside organizations. This report answers these questions.

This report finds that the BDS movement’s success on campus is mixed, while its broader movement is well-funded and growing in influence. This report notes that:

- Academia constitutes a core institutional base for the broader BDS movement in the United States.

- Pro-BDS student groups such as SJP are connected to larger progressive organizations on the Left and amplify BDS pressure and broader anti-Israel sentiment both on and off campus.

- Anti-Israel professors are instrumental in animating and organizing the BDS movement.

- A number of pro-BDS organizations have varying ties to Palestinian terrorism.

- Student tactics to pressure college administrations to divest from Israel are thus far largely unsuccessful in securing divestment from targeted companies. Despite these policy failures, BDS politicizes the college campus by contributing to an environment of intimidation against Jewish students and supporters of Israel.

- The BDS movement is fully integrated in an ecosystem of anti-Israel progressive organizations that includes lawfare groups, lobbying groups, and nonprofit foundations.

This report expands beyond previous work on the BDS movement by examining its constitutive student groups in the context of its off-campus support organizations and funding. BDS in universities must be understood as one component of a larger left-wing social justice movement that politicizes higher education.

This report first describes the Palestinian origins and development of the campus BDS movement, before examining its rates of success and failure nationwide from 2005 to the Fall 2022 semester. Three campus case studies then examine how pro-BDS initiatives are propagated, how such anti-Israel measures affect anti-Semitism on campus, and how university administrations address the issue. The second half of this report examines the off-campus organizations that enable BDS student activism by means of training, legal assistance, and funding. This report also notes ties between BDS organizations and terrorism.

The in-depth case studies highlight factors that likely determine how BDS battles unfold within student bodies, student government, and interactions between student organizations and college administrators. The three campuses examined are Columbia University, the Ohio State University (OSU), and the University of California, Riverside (UCR). At the levels of student activism and government, the case studies reveal that building coalitions on and off campus influences the success of student divestment initiatives. Cases were selected based on their differing trajectories on BDS in order to control for different outcomes, and to ascertain trends of how struggles over BDS occur on campus.

At both Columbia University and OSU, where BDS resolutions succeeded and failed, respectively, off-campus support and activism helped determine the final result. Pro-BDS efforts failed at OSU largely due to the activist infrastructure built by the school’s Hillel chapter, which garnered support across the student body and beyond the campus community. Conversely, Columbia’s successful BDS resolution cannot be divorced from prominent anti-Israel figures on the university’s faculty, and the work of national BDS groups such as Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) and SJP. The case studies note that the aggression of student activists in promoting their causes similarly influenced the outcomes of divestment resolutions. At UCR, pro-BDS students succeeded in passing resolutions and securing campus victories by means of persistence and by directly approaching bureaucracies on campus.

The second half of this report documents the origins and ties of the pro-BDS movement that help groups such as SJP and JVP expand their influence, as well as the economics of their activism. Campus BDS resolutions are specific in their endeavor to induce colleges to divest from Israeli companies and companies deemed complicit in Israel’s “occupation” of Palestinian territory as viewed through academic theories of “settler colonialism.” Because campus BDS resolutions name specific companies and investment funds, the economics underpinning the campus BDS movement are a key theme of this report.

BDS efforts on campus are supported by networks of anti-Israel academics, lawfare groups such as Palestine Legal and the Center for Constitutional Rights, and left-wing foundations that finance anti-Israel activism. Findings in this report note ties between the BDS movement and terrorist groups, particularly Hamas and the People’s Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

All supporting evidence in this report is open-sourced, and includes evidence from other studies on BDS, social media posts, statements from college administrators, media reports, corporate statements, investigative reporting from nonprofit watchdog groups, and governmental outlets.

Countering BDS and Maintaining Free Speech on Campus

This report offers two types of recommendations, both of which prioritize the principle of free speech. As the BDS movement inherently seeks to politicize campus bureaucracies against pro-Israel students and professors, it is fundamentally against the free speech and expression that a healthy collegiate environment requires to function. The first set of recommendations is designed for pro-Israel groups to counter BDS while respecting freedom of expression on campus and upholding the political neutrality of the university. The second set of recommendations focuses on legislation designed to curtail campus anti-Semitism and ensure the political neutrality of universities.

Recommendations include:

- Create programs similar to Birthright Israel to cater to non-Jewish students and replicate its success among a wider population.

- Amend anti-BDS laws to implement courses on the Holocaust and Israel in order to standardize a baseline of coursework on Israel and anti-Semitism at the college level.

- Counter the one-sided economics of on-campus anti-Israel activism through creating Abrahamic Academic Centers that include programs related to Israel and its new Arab partners. The creation of such centers expands discussions of Israel to broader issues beyond the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and helps reduce BDS proponents to one set of voices of among many.

- Amend anti-BDS laws to penalize universities that offer funding or support to pro-BDS groups. Thirty-five states have anti-BDS legislation, and such legislation should expand to restrict state funding for colleges that support anti-Israel student organizations.

- Amend anti-BDS laws to divest state pension funds from companies boycotting Israel in order to disincentivize companies from cratering to BDS pressure.

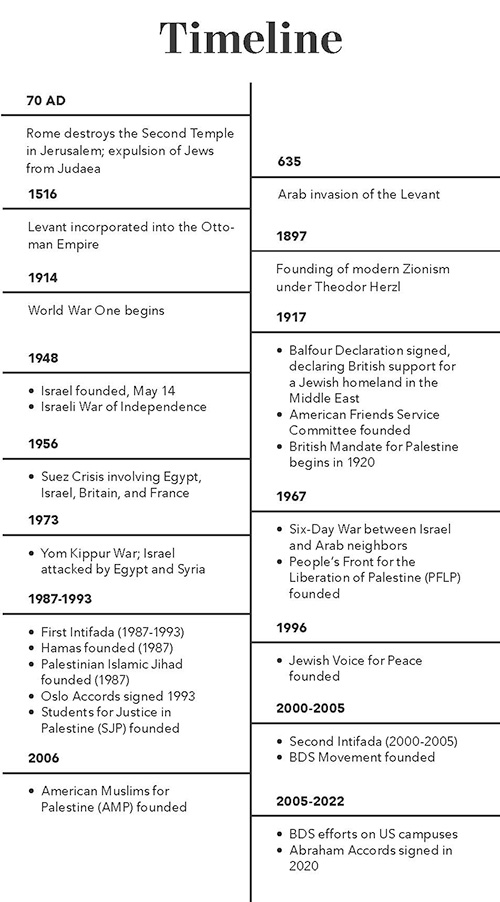

Timeline

Introduction

Rising anti-Semitism on college campuses coincides with the growth of the “Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions” (BDS) movement. Multiple reports document the anti-Semitism associated with BDS and describe the increasing unease experienced by Jewish students in universities. However, few studies on BDS examine the placement of anti-Israel activism within the institutional geography of the broader progressive movement that supports it. This report describes how BDS activism unfolds on campus, and how the BDS movement is enabled and funded by organizations connected to terrorism and progressive philanthropy.

On the surface, BDS appears to constitute a narrow movement based around the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Indeed, the anti-Israel BDS movement formed in Ramallah by issuing a “call to action” in 2004 and collaborating with Palestinian terrorist groups beginning in 2007.2 After its founding, the BDS movement exponentially grew in the United States through the formation of an extensive network of anti-Israel student groups, legal organizations, and nonprofits.

The movement’s ostensibly Palestinian origins obfuscate the important role that professors and academia play in its growth and influence in the West. Academics formed the first major pro-BDS organization, the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI). Professors similarly helped create PACBI’s US affiliate, the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (USACBI), and Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP).3 Institutionally, academia assists the BDS movement’s ability to project influence off campus and connect its campus activism to logistical funding and support.

The BDS movement threatens the integrity of universities due to its attempt to capture university policy to suit its own political goals. Far from a movement centered exclusively on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, BDS operates as part of a larger progressive, left-wing movement that is well-funded and connected beyond the university. The placement of BDS within a larger ecosystem of progressive political organizations affords it legal support, ties to electoral politics, and funding from a network of charitable foundations oriented toward social justice.

The campus-based BDS movement does not operate in isolation or seek purely symbolic political victories. Student BDS resolutions demand activist oversight of university finances and investments, and entail the bullying and intimidation of Jewish students, professors, and those who support Israel. The BDS movement’s political ties and broader funding present universities with an increasing challenge to ensure freedom of expression while reducing the anti-Semitism that it foments.

This report seeks to expand beyond previous studies of the BDS movement by examining how activist pressures unfold on campus, and how BDS allies with a broad and well-funded network of political activist organizations. As this report illustrates, BDS enjoys mixed success across campuses in passing resolutions that result in college administrators altering their investment policies toward Israel. Whereas BDS largely fails at convincing colleges to divest institutional portfolios from companies deemed to be associated with Israel, it is successful in fostering a politicized and hostile campus climate and influencing broader political discourse.

This report highlights the importance of coalition-building in the BDS movement’s ability to garner support. BDS groups present their cause through a rhetorical framework of anti-colonialism and anti-racism that resonates with the broader left-wing political landscape. The deployment of this ideological framework embeds BDS within academia due to the predominance of critical theory, identity politics, and grievance studies in today’s colleges and universities. Groups such as SJP and Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) are increasingly effective in martialing broad support for BDS initiatives across student bodies and campus governments.

This report begins by describing the emergence of the BDS movement in the Middle East in the aftermath of the Second Intifada with the founding of PACBI, and the movement’s growth on American campuses through the formation of student groups such as SJP. Chapter 2 examines the effectiveness and presence of student BDS efforts nationwide along with bodies of legislation passed to counter it. A majority of state governments have passed anti-BDS laws through either legislative action or executive orders designed to penalize companies that divest from Israel for political reasons.

Chapters 3–5 examine how BDS activist efforts unfold at the campus level in order to understand determinants of the movement’s success and failure. These chapters consist of case studies chosen based on the BDS movement’s success rate at that campus, and include an examination of Columbia University, the Ohio State University (OSU), and the University of California, Riverside (UCR). Columbia exemplifies a case in which attempts to pass BDS resolutions at the campus level failed before succeeding. Columbia’s administration refused to acquiesce to activist demands for divesting from key companies deemed affiliated with Israeli aggression. In the case of UCR, BDS efforts unfolded in an alternating series of success and defeat. Conversely, OSU offers a case in which BDS activists repeatedly failed as the result of organized student opposition. The case studies underscore common themes of university administrations proving reluctant to follow BDS demands while also tolerating increasing hostility toward Jewish students and the politicization of campus life. Across all cases, the abilities of student groups to form coalitions of support across student bodies, and with outside organizations from beyond the university, proved a deciding factor of BDS outcomes.

Chapters 6 and 7 describe the ties between the campus BDS movement and organizations beyond the university. Chapter 6 describes ties between student BDS organizations, their national support networks, and terrorist groups in the Middle East such as Hamas and the People’s Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Chapter 7 examines BDS funding, and how the movement is supported by an ecosystem of legal groups and progressive non-profit foundations.

The final component of this report offers recommendations for both pro-Israel civil society and for legislators to craft legislation designed to curtail funding for the BDS movement. The bifurcation of recommendations is meant to help counter the anti-Semitic and politicized campus environment that BDS creates without weaponizing university administrations or empowering an academic environment that is already censorial. Due to existing anti-BDS laws, and laws against terrorist financing, the legal infrastructure to curtail activist bullying already exists in most states. This report’s legislative prescriptions aim to sever university funding for campus BDS groups in order to help safeguard or restore academia’s political neutrality on Israel.

The economics and funding of BDS are discussed throughout this report. BDS groups do not simply target Israel in their resolutions but also target specific companies and investment funds. Should a university acquiesce to divestment demands, such decisions signal to companies that business in or with Israel is an unaffordable risk. Similarly, BDS organizations are often well-funded by foundations and donations that have their origin in corporate giving. This report approaches BDS as a phenomenon of activist-driven economic warfare, and offers recommendations designed to counter it.

The Development of the BDS Movement’s Core Organizations

The Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI)

The anti-Israel Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement on American college campuses began in the Middle East. From 2000–2005, the Second Intifada witnessed an escalation of asymmetric warfare between Israel and a coalition of Palestinian groups that included organizations such as Hamas and the Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades. Alongside suicide bombings that targeted Israeli civilians, Palestinian groups increased their use of anti-Israel civil society diplomacy to undermine Western support for the Jewish state. One of these groups was the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI).4

PACBI formed in Ramallah in 2004 as a primarily academic-led organization comprising Palestinian professors operating out of Birzeit University.5 Drawing inspiration from international boycotts against South Africa under apartheid, PACBI set the tone of the BDS movement by framing it as a struggle against “colonial oppression of the Palestinian people, which is based on Zionist ideology.”6 By framing its activism as simultaneously “anti-colonial” and opposed to Zionism—which is the belief in and support for a Jewish state in Jews’ biblical homeland—PACBI and the BDS campaign embedded an ethno-religious conflict within broader left-wing narratives of anti-imperialism. Framing BDS within an “anti-imperialist” narrative explains the movement’s ability to appeal to progressive Western academia.

The BDS movement’s first episode of activism consisted of a “call” to the international community in order to increase pressure on Israel by enacting overlapping academic, cultural, and economic measures. In its original 2004 call, PACBI outlined a five-step plan of action that included a direct promotion of economic divestment from colleges and universities. This five-step plan included:

- Refraining from participation in any form of academic and cultural cooperation, collaboration, or joint projects with Israeli institutions.

- Advocating for a comprehensive boycott of Israeli institutions at the national and international levels, including suspending of all forms of funding and subsidies for these institutions.

- Promoting divestment and disinvestment from Israel by international academic institutions.

- Working toward condemnations of Israeli policies by pressing for resolutions to be adopted by academic, professional, and cultural associations and organizations.

- Directly supporting Palestinian academic and cultural institutions without requiring them to partner with Israeli counterparts as an explicit or implicit condition for such support.7

Because universities often receive multiple streams of funding through grants and government funds, and hold ties to the private sector through endowments and pensions, university finances are a core focus of PACBI activism.

PACBI is structurally linked to Palestinian political groups that include terrorist organizations. In 2007, PACBI helped found the Palestinian BDS National Committee (BNC), which serves as a coalition of organizations advocating for punitive economic measures against Israel.8 One of the BNC’s organizational members is the Council of National and Islamic Forces in Palestine (PNIF), which itself comprises five different terrorist organizations: Hamas, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the Popular Front-General Command (PFLP-GC), the Palestinian Liberation Front, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ).9 The BNC, of which both PACBI and the PNIF are members, is funded in part by the US-based nonprofit US Campaign for Palestinian Rights (USCPR).10 As of 2018, the USCPR had supported 329 different BDS groups along with the BNC.11 On July 15, 2017, the BNC hosted an anti-Israel webinar with Pink Floyd rock star Roger Waters that was promoted by the USCPR.12

In the US, PACBI’s funding and influence are tied not only to the Democratic Party but also to US-based funding mechanisms that allow it to support its campus activism. In the formal political landscape of American electoral politics, PACBI donations are facilitated by ActBlue, the primary online donation platform for the Democratic Party.13 In February 2021, Zachor Legal Institute, a pro-Israel thinktank and legal watchdog, began pressuring ActBlue to “investigate” its facilitation of donations to PACBI.14 The Zachor Legal Institute asserted that despite PACBI’s de-platforming by other funding sites, ActBlue continued to allow PACBI to fundraise through its portals under ActBlue Charities.15 As of this writing, PACBI remains listed for donations through ActBlue.16 Three key organizations serve as pillars connecting PACBI to campus BDS activism: the USCPR, the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (USACBI), and the student activist group Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP).

The US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (USACBI)

In late 2008, Jerusalem launched a military operation in the Gaza Strip in response to rocket attacks against civilians in southern Israel. The Gaza War of 2008–2009, called Operation Cast Lead by Israel, only lasted 22 days. The Gaza War catalyzed the creation of an American affiliate of PACBI. This US affiliate materialized as the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (USACBI).17 In January 2009, USACBI declared its formation as an answer to PACBI’s “call” for boycotting Israel, and issued a statement aligning itself with its Palestinian counterpart. USACBI declared:

We believe it is time to take a public, principled stance in support of equality, self-determination, human rights (including the right to education), and true democracy, especially in light of the censorship and silencing of the Palestinian question in US universities, as well as US society at large. There can be no academic freedom in Israel/Palestine unless all academics are free and all students are free to pursue their academic desires.18

As an organization, USACBI boasts multiple academic groups and entities that support its boycott efforts.19 USACBI lists 1,565 academics who officially endorse the BDS cause.20 One of PACBI’s founders, a sociology professor from Birzeit University named Lisa Taraki, is a member of USACBI’s advisory board.21 Other advisory board members include the late Desmond Tutu, Angela Davis at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Ilan Pappé, and scholar-activists from across multiple disciplines.22

In 2015, USACBI formally launched several initiatives that amounted to a turning point for the organization’s campus activism. In addition to a “Speakers Bureau,” USACBI formed the Faculty for Justice in Palestine (FJP) and the USACBI Academic Defense Committee. The FJP is, essentially, a chapter-based organization embedded at different universities that spearhead pro-Palestinian and pro-BDS organizations on their respective campuses.23 Included among the FJP’s political demands is the controversial “Right of Return” of Palestinian refugees to Israeli territory.24 FJP’s first chapters opened at the University of Hawai’i, the University of California, Davis, Kent State University, the University of Florida, and Purdue University.25

The USACBI Academic Defense Committee was designed as a “national defense committee” in order to “provide letters of support, information, and resources,” as well as legal support, for pro-Palestinian individuals and organizations on campus.26 The Academic Defense Committee’s main focus is the “academic and cultural boycott of Israel” (ACBI). It is only one organization in a coalition of groups called the National Academic Defense Coalition (NADC).27 The NADC comprises a number of legal support organizations for pro-BDS activism, and includes an Academic Advisory Council affiliated with Jewish Voice for Peace,28 the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network,29 the Open University Project at Columbia University,30 and Palestine Legal.31 These legal groups often help pro-BDS student organizations which advocate for anti-Israel initiatives, and frequently offer assistance when anti-Semitic incidents arise on campus.

The USACBI notes that this legal defense initiative developed alongside the American Studies Association’s endorsement of BDS.32 USACBI explicitly states that its legal defense initiatives are not merely defensive, but that those who enjoy the organization’s backing and support BDS are engaged in “an expression of antiracist activism.”33 The USACBI conceptualizes itself and the broader BDS movement as part of a larger struggle for academic freedom, and views pro-Israel activism as part of a “neoliberal restructuring of the university.”34

Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) and American Muslims for Palestine (AMP)

Students for Justice in Palestine is the primary student organization behind the BDS movement on American college campuses. SJP largely emerged out of an older Palestinian student organization, the General Union of Palestinian Students (GUPS). The GUPS grew out of proto-Palestinian nationalism as early as the 1920s, and officially formed in Egypt in the 1950s.35

Multiple leaders of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) began their careers as GUPS members, with Yasser Arafat being one of the most notable of the group’s alumni.36 The GUPS was a primary link between students in the Palestinian diaspora and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and was the first student organization to call for a political and military entity devoted to Palestinian nationalism.37 Initial relations between the GUPS and the PLO were rocky due to disputes over recognition and hierarchy; however, Yasser Arafat “normalized” relations between the international student group and the Palestinian movement’s core political organization.38 Ultimately, most GUPS chapters in the US closed, with San Francisco State University’s (SFSU) chapter standing as an exception.39

The Oslo Accords and the creation of the Palestinian Authority led to the closure of most of the GUPS chapters in the United States. At its height, the GUPS boasted a presence at 60 colleges and universities; however, the number of chapters steadily declined over the 1990s as the result of internal ideological conflicts and the more nebulous international status of the PLO alongside the Palestinian Authority.40 Notably, one of the reasons the GUPS chapter at SFSU survived is because of the extra support it was provided by the university. SFSU’s College of Ethnic Studies provided institutional support for the organization.41 SFSU’s chapter also secured funds through independent fundraising and money provided by the university’s Associated Students.42

The GUPS remains active at SFSU and drafted the language of the university’s BDS resolution in 2020.43 On November 18, 2020, SFSU’s Associated Students overwhelmingly passed a resolution calling for the university to divest from companies in Israel. The vote, which passed 17–1, had speakers from numerous organizations in favor of the resolution’s passage. Such organizations that supported the move included the Black Student Union, the League of Filipino Students, and the International Business Society.44 SFSU’s Hillel director, Rachel Nilson Ralston, noted that many students faced “extreme pressure and bullying tactics from activists across the country” to coerce them into supporting the move.45 In response to the resolution, SFSU’s president Lynn Mahoney declared that the university would not adopt “a divestment position with no global context of acceptance of the complexities at hand.”46 Mahoney’s response parallels the responses of other university administrators, and exemplifies how the BDS process succeeds at the student level while failing to change university policies on American campuses.

The national decline of the GUPS coincided with the emergence of SJP. Founded in 2001, SJP serves as the primary student activist group behind the BDS movement in the US. It grew out of a single GUPS chapter at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley).47 Hatem Bazian, a Palestinian-born graduate of SFSU and member of the GUPS, founded a separate chapter at Berkeley that was rebranded as SJP.48

Bazian is currently a professor at Zaytuna College and a lecturer at UC Berkeley’s Department of Ethnic Studies.49 His scholarly background combines theological work in subjects such as Islamic law and Classical Arabic with the progressive academic subjects of “Race Theory and History, Colonialism, Post-Colonial and De-colonial Studies.”50 Bazian’s activism proved instrumental in crafting SJP into a national force behind the BDS movement. By the mid-2000s, SJP began operating under a coordinating umbrella organization through the Palestinian Solidarity Movement (PSM). PSM was formed by the group American Muslims for Palestine (AMP). Bazian founded AMP in 2006 and shaped much of the organizational infrastructure for BDS student activism.51 He remains the chairman of the organization.52

Both AMP and SJP have significant influence in progressive political circles and enjoy a nominal breadth of success on campuses in passing BDS resolutions in student governments. While BDS efforts on campus are better known, AMP also operates at a higher level of political activism through lobbying and pressuring policymakers. AMP’s political profile increased in recent years alongside the increasing prominence of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.

At AMP’s 2019 annual conference, congresswoman Rashida Tlaib (D-MI) appeared as a speaker alongside activists such as Linda Sarsour.53 In her remarks at the conference, Tlaib drew comparisons between US policies on the US–Mexico border and Israeli policies on Gaza.54 The AMP conference illustrates the growing ideological confluence of AMP and the Democratic Party.

In 2021, both congresswoman Tlaib and congresswoman Betty McCollum (D-MN) supported legislation with its origins in AMP.55 In April of that year, McCollum introduced a bill titled the Defending the Human Rights of Palestinian Children and Families Living Under Israeli Military Occupation Act, that would curtail Israel’s use of US financial assistance in security operations in the West Bank and “East Jerusalem.”56 AMP endorsed the resolution alongside multiple Democratic House members:

- Bobby L. Rush (IL-01)

- Danny K. Davis (IL-07)

- André Carson (IN-07)

- Marie Newman (IL-03)

- Ilhan Omar (MN-05)

- Mark Pocan (WI-02)

- Raúl Grijalva (AZ-03)

- Rashida Tlaib (MI-13)

- Ayanna Pressley (MA-07)

- Cori Bush (MO-01)

- Jamaal Bowman (NY-16)

- Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez (NY-14)

- Jesús “Chuy” García (IL-04)

Not only is AMP’s political influence growing and threatening the traditionally bipartisan nature of pro-Israel legislation in Washington, but the group retains ties to terrorist groups operating in the Palestinian Territories.

AMP’s executive director, Dr. Osama Abuirshaid, is a firebrand of the BDS movement at the level of national American politics, and regularly employs classically anti-Semitic rhetoric when discussing Israel. In an interview with Jordan’s Yarmouk TV about US financial support for Israel’s Iron Dome, Abuirshaid declared, “We are witnessing the closing of the ranks, and an emphasis on the force that supports Palestine within the Democratic Party.”57 Drawing inspiration from classic anti-Semitic rhetoric equating Jews with parasites, Abuirshaid declared that Israel

is a case of a parasite living off the American body. America is going through an economic crisis. America is suffering strategically. It is suffering in many places in the world. It is withdrawing from many places in the world—from Afghanistan, from the Middle East, from other places, because it wants to focus its energies on the rising Chinese dragon. Nevertheless, Israel pulls America back. It sucks the blood of America, and it scatters its attention.58

In November 2021, only months after McCollum introduced her AMP-endorsed bill, Abuirshaid attended a conference in Jordan titled “Towards the Features of a New Arab Strategy to Deal with the Arab-Israel Conflict” that included representatives from Hamas and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).59 At the conference, Abuirshaid linked the BDS movement’s goals with progressive narratives in the US. Abuirshaid again drew parallels between Israel’s alleged apartheid policies, segregation in the US, and American policies regarding the US–Mexico border.60 Notably, Abuirshaid, a US citizen, only obtained citizenship in 2017 after an eleven-year delay for links to terrorist groups.61

AMP’s work and strategy is similar to that of the pro-Israel advocacy group AIPAC (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee), in that it seeks to leverage political and activist influence in order to secure economic policy objectives. Reflecting AIPAC’s efforts to secure US legislation and funding to support Israeli security, AMP seeks to eliminate funding and curtail US support for Israel. AMP, and the BDS movement as a whole, seek to replicate the success that the African National Congress had in economically isolating South Africa prior to the end of Apartheid in 1994. If SJP-led campus resolutions declaring support for the BDS movement constitute “low-level” activism, AMP’s efforts exhibit a higher political altitude of the same movement by means of a separate but allied organization.

SJP chapters are ostensibly autonomous organizations connected by a collective adherence to shared policy goals. Such goals include: an end to Israel’s “occupation and colonization” of Palestine, the destruction of Israel’s security barrier, the granting of “full equality” to Israeli-Arabs, and the return of Palestinians displaced by Israel’s creation.62 This autonomy of SJP chapters has allowed individual chapters to promote more radical policy goals in both campus demands and in the real political realm.63 This form of autonomous, loose coordination under a single brand allows for the BDS movement to innovate and organically grow a bench of activists for higher levels of advocacy while simultaneously insulating the whole of the movement from the closure or sanction of a single chapter. Recent estimates from 2017 count 189 active SJP chapters in the United States.64

A notable factor of the SJP is its exclusively political nature. Rather than focus on political issues alongside other aspects of Palestinian life, SJP eschews events promoting Palestinian Arab culture, the Arabic language, and other non-political activities.65 Due to this singular political focus, SJP similarly shuns “faith-washing,” or dialogue with pro-Israel groups and Jewish organizations.66 While the SJP is the flagship organization of the student BDS movement, it does have smaller allied organization similar to GUPS at SFSU. Such groups include Canada’s Students for Palestinian Human Rights, Students Against Israeli Apartheid, and Harvard’s Palestine Solidarity Committee (PSC).67

SJP employs theatricality and confrontation in its protests; such tactics constitute key elements of its branding and strategy. Staples of SJP publicity campaigns include “Apartheid Wall” displays, mock evictions of students in campus dorms, mock checkpoints that dramatize interpretations of Israeli security checkpoints, and its signature “Israel Apartheid Week” of annual activism events. These theatrical and melodramatic forms of activism capture most of the public’s attention of the BDS movement, creating a campus climate of intimidation and anti-Semitism. This activism also positions SJP as an attractive partner to other radical campus groups seeking allied organizations for parallel causes.

SJP enjoys allies from an array of student organizations based on the politics of identity and grievance. Such organizations are often integral to SJP’s efforts to pass divestment resolutions on campus. This coalition of pro-BDS organizations collaborating with SJP unites around the political logic of critical theory that predominates in the modern university, and is based around a worldview comprising oppressors and the oppressed.

This dynamic unfolds under the assumptions of “intersectionality,” where identity groups deemed “marginalized” find common cause with one another in battling “colonialism” in campus activism alongside similar “oppressed” groups.68 Due to the largely successful attempts of pro-Palestinian groups to portray Israel as a neo-colonial project akin to Apartheid-era South Africa, many campus groups align with SJP.

The success of BDS at Columbia University derives from the combined effort of SJP and JVP that resulted in the founding of Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD).69 At Columbia, CUAD acts as an umbrella for the pro-BDS movement, despite the SJP serving as its core activist engine. After several failures to pass a BDS resolution, Columbia passed its first BDS referendum in 2020.70 At Columbia, SJP’s efforts were far from isolated, as the group’s intersectional appeals led to multiple endorsements from student groups far-removed from the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The expanse of such endorsements highlights SJP’s organizational reach and collaborative power. The BDS movement is not a fringe campus element, but rather a part of the campus mainstream where it is present. The student groups at Columbia that supported BDS include a broad progressive coalition listed below.71

Figure 1.1

- Asian American Alliance

- Asian Political Collective

- Barnard-Columbia Socialists

- Barnard Organization of Soul and Solidarity

- Barnard-Columbia Prison Abolition Coalition

- Barnard-Columbia Middle Eastern and North African Women’s Association (MENA)

- Black Reading Group

- Caribbean Students’ Association at Columbia University

- Charles Drew Pre-Medical Society

- Chicanx Caucus

- Columbia Divest for Climate Justice

- Columbia Journal of Literary Criticism

- Columbia Muslim Students Association

- Columbia Queer Alliance

- Columbia University Black Students Organization

- Columbia University Club Bangla

- Columbia University Historical Journal

- Columbia University Historical Justice Initiative

- Columbia University Organization of Pakistani Students

- Columbia University Turath

- Columbia-Barnard Young Democratic Socialists of America

- Divest Barnard from Fossil Fuels

- Echoes Art and Literary Magazine

- Ethio-Eritrean Student Associations

- Extinction Rebellion Columbia University

- GendeRevolution

- Housing Equity Project

- Journal of Art Criticism

- Lutherans, Methodists, and Presbyterians Progressive Protestant Campus Ministry

- Muslim Afro Niyyah Students Association

- National Society of Black Engineers

- Native American Council

- No Red Tape

- Proud Colors

- South Asian Feminisms Alliance

- Student-Worker Solidarity

- Students Helping Students

- Students Organize for Syria

- UndoCU

SJP, naturally, draws accusations of anti-Semitism, accusations of harassment and intimidation, and occasional assault allegations made by Jewish students who claim the group creates a hostile environment for Jews. A 2016 report from Brandeis University discovered that the presence of an “active” SJP chapter on a college campus is one of the strongest indicators for Jewish students to perceive a university environment as hostile and anti-Semitic.72 The study also found that schools in the Northeast, Northwestern University, and the University of California were found to be anti-Semitic “hotspots” where hostility toward Jews and Israel was deemed to be high.73 The 2016 Brandeis findings are not isolated, but are confirmed by a 2021 study that noted 65% of Jewish students felt unsafe on campus.74 The perception of an anti-Semitic campus environment that corresponds to the presence of SJP is supported by multiple incidents involving intimidation that threatened to escalate into violence. Several of SJP’s centerpieces of direct-action activism involve confrontational tactics that contribute to anti-Semitic campus environments. While not an exhaustive list of the group’s performative activism, SJP’s mock evictions, mock Israeli checkpoints, and mock “Apartheid Wall” in particular foster a broader anti-Semitic environment.

At Emory University in 2019, the school’s SJP chapter posted “eviction notices” in the college’s dormitory halls warning residents that their “suite is scheduled for demolition in three days.”75 Notably, Emory’s Office of Residence Life and Housing Operations allowed the posting of the flyers, despite SJP’s violation of the university’s policy against posting flyers on doors.76 SJP’s hostile theatrics led to Emory’s campus police receiving numerous complaints from the students who received the flyers.77 That same year at New York University (NYU), SJP received the school’s President’s Service Award for having “positively impacted the culture” of the university.78 NYU’s actions culminated in a complaint filed with the Department of Education that accused the university of violating the Trump administration’s addition to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.79 UC Berkeley was sued in 2011 by a Jewish student for failing to protect her civil rights when she was allegedly assaulted by a SJP student member during the group’s Israel Apartheid Week.80 In 2001, when SJP was still a new activist group, 79 people were arrested at a SJP sit-in protest at UC Berkeley’s Wheeler Hall.81 Seven students were accused of resisting arrest, including one student who allegedly bit a campus police officer as the protest was broken up.82

While SJP’s intersectional calls to action bring the organization allies from campus groups and help it secure the passage of BDS resolutions, the group’s reputation often proves problematic for college administrations. Administrators at Fordham University in 2015 rejected the formation of a SJP chapter, under the logic that the organization’s “political goals” would be “polarizing” on campus.83 Fordham’s decision ultimately resulted in a 2017 lawsuit filed by SJP, which was represented by Palestine Legal, the Center for Constitutional Rights, and attorney Alan Levine.84 After a court decision mandating that Fordham recognize the group, an appellate court overturned the ruling. The New York Court of Appeals ultimately denied SJP’s further appeal, backing the Fordham administration.85

Both AMP and SJP face continual accusations of anti-Semitism from pro-Israel groups, conservatives, and Jewish organizations.86 Despite the allegations, both AMP and SJP deny the anti-Semitism in their organizations and officially condemn it. On its official website, AMP posts an “Anti-Bigotry Statement” declaring that the organization “is categorically opposed to all forms of racism and bigotry, including Islamophobia, anti-black racism, anti-immigrants, anti-Semitism, and other forms of bigotry directed particularly toward people of color and indigenous peoples everywhere.”87 Similarly, SJP declares that it will “continue to fight against white supremacy, Zionism, antisemitism, Islamophobia, sexism, capitalism, militarism, imperialism, homophobia, transphobia, and all other political institutions that continue to oppress marginalized folks.”88 In 2014, SJP at Vassar College hypocritically used a vintage Nazi propaganda poster on social media that led the college to launch an investigation into the group for its use of the poster as a “bias incident.”89 Pro-BDS organizations on college campuses deflect accusations of anti-Semitism by couching their platform within the broader progressive political ideology that dominates the university.

This chapter serves to give an overview of the primary organizations and groups empowering the BDS movement on American campuses. Other organizations similarly support the BDS movement and the pro-Palestinian cause elsewhere in the country’s sociopolitical landscape, or to a lesser degree than the organizations mentioned above. However, the aforementioned organizations constitute the core of the BDS movement, link campus activism with political advocacy at the national level, and connect Israel as an issue of American politics to the political dynamics in the Middle East. The following chapter offers an overview of how BDS efforts succeed and fail by offering analysis and history of the movement on three campuses.

The BDS Movement on Campus: Anti-Semitic Menace or Paper Tiger?

The BDS movement constitutes an acute flashpoint of confrontational student activism. Unlike other campus causes, such as climate change, where the activism is virtually one-sided, the BDS movement faces natural opposition from Jewish student organizations and other supporters of Israel. The fact that pro-BDS student groups such as SJP are often supported by broad progressive student coalitions nonetheless creates a markedly politicized and hostile campus environment. While most Jewish students on campus may forego involvement in pro-Israel activism, the anti-Semitic overtones and activities of the BDS movement help foster a broader sense of insecurity among Jewish students and others who may support Israel.

This chapter assesses the BDS movement’s effectiveness on campus by examining three metrics by which to measure its successes and failures. The first metric is how successful the BDS movement is at passing anti-Israel resolutions at the student government level. The second metric is the degree to which these resolutions from the student government level translate into university policy in the form of academic and economic boycotts, with a particular focus on whether universities follow through on student demands to divest from companies that do business in Israel. The last metric is whether the on-campus BDS movement is successful in shaping political activity beyond the confines of the university and into the broader political environment. As will be shown below, the overall effectiveness of the BDS movement on campus is mixed.

Success and Failure of BDS Resolutions

Multiple studies have covered the BDS movement on college campuses and have tracked its development since 2005, with the most work coming from the American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE). Research conducted by AICE depicts a BDS movement that is vocal, acute, but ultimately narrow in its reach and shallow in its ability to achieve policy victories. Between 2005 and 2022, 150 BDS resolutions were initiated on college campuses, while 98 failed as the result of vetoes, repeals, and simply being voted down.90 Similarly, votes occurred at 73 schools out of the 4,298 four-year colleges included in the study, meaning the 44 BDS approvals represent 1% of American universities.91 In summation, BDS resolutions over this timespan have a 66% failure rate.92 Notably, BDS resolutions are often voted down both when they appear as student government initiatives and when they are attempted through student referenda.93 Despite failure characterizing the overall trend of student-led attempts to achieve BDS resolutions, some universities pass such resolutions. With large studies already indicating a limited campus effectiveness of BDS, the question remains regarding how such attempted resolutions take place.

Campus BDS efforts significantly increased over the past several years, and against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, greater polarization in US politics, and the 2020 riots following the death of George Floyd. The 2020–21 academic year had more successful passages of BDS resolutions than any other year since the movement began.

Figure 2.1: BDS Resolutions Success/Failure Rate as Of June 2022 (Source: AICE)

| BDS Wins | BDS Wins | BDS Losses | Total Resolution Votes | Failure Rate |

| 2021–22 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 100% |

| 2020–21 | 9 | 5 | 14 | 36% |

| 2019–20 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 100% |

| 2018–19 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 80% |

| 2017–18 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 64% |

| 2016–17 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 67% |

| 2015–16* | 7 | 11 | 18 | 61% |

| 2014–15 | 7 | 20 | 27 | 74% |

| 2013–14 | 7 | 11 | 18 | 61% |

| 2012–13 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 60% |

| 2011–12 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 60% |

| 2010–11 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 50% |

| 2009–10 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| 2008–9 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| 2007–8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% |

| 2006–7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0% |

| 2005–6 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 50% |

| Total | 53 | 97 | 150 | 65% |

| % | 35% | 65% | Source: AICE94 | |

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) notes that one of the engines behind the BDS movement’s success in the 2020–21 school year is its ability to connect anti-Israel activism with larger left-wing causes on campus. Specifically, such BDS strategies include equating support for the Jewish state with support for racism and conceptually separating support for Israel from the Jewish faith.95 On campuses where conflagration occurs between the BDS movement and broader social justice–driven activism, anti-Israel activity intensifies to exclude pro-Israel students and Jewish students from student life and deepens from criticism to essentialist anti-Semitic tropes. This activism is not limited to student organizations—it also includes professors. The ability of pro-BDS groups to attach anti-Israel activism to broader left-wing initiatives contributes not only to anti-Semitism but also to a larger politicization of college campuses that threatens academic openness and the institutional neutrality of the university.

From fall 2020 to winter 2021, Rose Ritch, vice-president of the University of Southern California’s Undergraduate Student Government, faced an intense, anti-Semitic publicity campaign that ultimately led to Ritch’s resignation. In the aftermath of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests and the accompanying riots, Abeer Tijani, a Nigerian-born senior at USC, launched impeachment efforts against Ritch and student body president Truman Fitch on the grounds that they did not “authentically represent nor promote the true breadth of diversity that our community has to offer.”96 Despite USC’s administrative efforts to contain a growing publicity frenzy on social media, Jewish Voice for Peace, the Council on American-Islamic Relations Los Angeles, the Middle East Studies Association of North America, and the California Scholars for Academic Freedom reasserted what they viewed as a false continuity between Fitch’s support for Israel and her Jewish identity.97 One student at USC, Yasmeen Mashayekh, an engineering student listed as a “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion senator,” tweeted her desire to “kill every mother---g Zionist.”98 After weeks of harassment and intimidation, Ritch ultimately resigned from her position. USC’s SJP chapter supported the pressure campaign.99

On June 14, 2020, University of California, Merced (UC Merced) professor Abbas Ghassemi promoted a social media campaign equating Zionism to classically anti-Semitic portrayals of Jews. In a series of social media posts dating from the latter half of 2020, Ghassemi speculated about the makeup of the “Zionist brain” and made repeated accusations about the US government, American banking, and the media being controlled by Israel.100 UC Merced’s administration ultimately opened an investigation into the postings, stating that the school must “not let anti-Semitism or any form of bigotry or hate toward any group take root in the UC Merced community.”101 Less than a year later, UC Merced and SFSU planned to host an online event titled “Free Speech and Palestine” featuring PFLP hijacker Leila Khaled. The event, which was cosponsored by SFSU’s program for Arab and Muslim Ethnicities and Diasporas Studies and the University of California Humanities Research Institute, drew condemnation and requests for cancellation from the Lawfare Project, which asserted that both schools could be in violation of US counterterrorism laws.102 The event was ultimately canceled, but it would have included former Black Panther Sekou Odinga and former Weather Underground member and convicted terrorist Laura Whitehorn.103 UC Merced passed its BDS resolution in April 2016.104

The BDS movement’s work at decoupling perceptions of traditional anti-Semitism from anti-Israel activism has proven incredibly successful at blunting accusations of anti-Semitism made against groups such as SJP. At Duke University in 2022, the student government unanimously passed a resolution condemning anti-Semitism and adopting the definition of anti-Semitism given by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA).105 The measure passed by Duke’s student government included training for student senators and others.106 Only a month after this resolution, the same student government allocated $16,000 to SJP in order to host anti-Semitic speakers and an event entitled “Narrating Resistance and Agency: Shifting the Discourse on Palestine.”107 One of the speakers at the event, Mohammed El-Kurd, is noted by the ADL for accusing Israelis of organ-harvesting and claiming that the cannibalism of Palestinians is due to Israelis’ “unquenchable thirst for Palestinian blood.”108 The fact that the BDS movement’s premier organization funded a speaker making classical anti-Semitic references did not faze the Duke University student government.

SJP’s image as a general left-wing organization, rather than an exclusive group devoted to a niche issue, is further seen by the actions of the chapter at the University of Chicago in early 2022. In the wake of the shooting of an Asian student in an armed robbery near campus in late 2021, a group of predominantly Asian international students organized a list of demands for increased campus safety.109 In response, a coalition of student organizations, SJP among them, condemned the pro-safety students for being ostensibly pro-police.110 SJP specifically stated that it “supports the complete abolition of prisons and policing as essential for racial equality.”111 While SJP has a devoted focus as part of the BDS movement and is arguably the movement’s core on-campus organization, it also operates as one segment in a broader mosaic of progressive groups and causes. Despite the BDS movement’s marked success in passing resolutions where it is present on campus, most schools in the US have no discernable BDS activity.112 According to research conducted by AICE, most college administrators are resistant to divesting funds from Israeli companies, companies that do business with Israel, and Israeli universities.113 This reluctance contrasts with the BDS movement’s occasional successes abroad and with fossil fuel divestment efforts in the US. In the United Kingdom, both the University of Manchester and the University of Leeds have divested from companies deemed to be involved in human rights abuses in Israel.114

SJP’s Imagined Success: Hampshire College and the War on Israeli Hummus

In 2009, Hampshire College divested from an investment fund called State Street that included six companies doing business in Israel: United Technologies, Caterpillar, Motorola, Terex, ITT, and General Electric.115 State Street was judged by the college’s director of communications, Elaine Thomas, to have held shares in “well over 100 companies engaged in business practices that violate the college’s policy on socially responsible investments. These violations include unfair labor practices, environmental abuse, military weapons manufacturing, and unsafe workplace settings.”116 Hampshire College’s Board of Trustees noted that the decision was based in part on the activism from the school’s SJP chapter, though the consideration itself “did not pertain to a political movement or single out businesses active in a specific region or country.”117 While the BDS movement held up Hampshire College’s divestment as a major win, several factors make the school an outlier and call into question whether the case is a victory for the movement.

Hampshire College was the first school in the US to divest from South Africa under Apartheid, indicating the institution may simply be ideologically primed to support left-wing causes in general rather than being specifically anti-Israel.118 Additionally, divisions within the school’s administration and leadership are indicated by the school’s response to criticism of the divestment move from the ADL. After criticism from the ADL and attorney Alan Dershowitz, Hampshire president Ralph Hexter responded by stating that the decision to divest was not focused on Israel, but was made independently of Israel.119 Hexter and the chairman of Hampshire’s Board of Trustees, Sigmund Roos, stated that “no other college or university should use Hampshire as a precedent for divesting from Israel, since Hampshire has refused to divest from Israel. We have stated this publicly.”120 In either scenario, the BDS movement itself seemed only to have an indirect effect on Hampshire’s decision.

Other purported BDS victories are minor in terms of actual boycotts, such as colleges attempting to boycott the hummus brand Sabra. A year after Hampshire divested from State Street, DePaul University and Princeton University both attempted to divest from the hummus-maker Sabra. At the time, Sabra was an American company based in New York and Virginia, but was co-owned by the Israeli food giant Strauss Group.121 At DePaul, boycott efforts commenced with SJP calling on the administration to ban the sale of Sabra hummus on campus; however, despite the quick and minor victory for SJP, the school shortly reversed its decision.122 After the reversal, SJP brought the issue to the student government at DePaul for a referendum vote in late May 2011.123 The vote to end the sale of Sabra hummus on campus passed with 80% voting in favor of the decision.124 Despite the victory, SJP’s activism was thwarted again by DePaul’s administration. DePaul’s Fair Business Practices Committee opted to keep the hummus brand for sale on campus.125 The committee deemed that banning the product was unwarranted.126 A similar student referendum was held at Princeton in late 2010; however, unlike at DePaul, students voted in favor of keeping Sabra.127

In contrast with their British counterparts, pro-BDS student governments in the US often meet a roadblock, with administrators refusing to follow through on BDS demands. The following chapters of this report describe this dynamic in detailed case studies of campuses that forced multiple attempts at passing resolutions. The common theme emerges that administrators at many schools view the BDS resolutions as a threat to academic freedom. Due to the BDS movement’s simultaneous attacks on ties between American and Israeli academic institutions, and on Israeli for-profit companies, the influence of pro-BDS student governments reaches only so far on college campuses when it comes to policy changes.

Influence of the On-Campus BDS Movement Off Campus

While setbacks for the on-campus BDS movement have thus far curtailed its ability to translate activism into policy controlled by administrators, the movement is beginning to enjoy greater political access to policymakers at the national level. Hyper-polarization amid the Democratic Party’s move to the left has created greater salience for the BDS movement and a more fertile political audience than in the past. At this higher political level, and in the US public at large, BDS is beginning to access those with greater authority in government and contribute to a more pro-BDS electorate.

American sentiment on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is well-known, as the US is generally pro-Israel. Despite this, sentiment is shifting along partisan lines. Data on how Americans view the BDS movement has been less understood until recently. According to a University of Maryland Critical Issues Poll conducted in the leadup to the 2020 election, more Democrats favor supporting the BDS movement than in the past. The poll discovered that 77% of Democrats held that the BDS movement more closely represented their views on the issue, and that the movement itself was not anti-Semitic.128 In contrast, Republicans held an opposite view, and did so more strongly, with 85% viewing BDS as inherently anti-Israel and likely anti-Semitic.129

This particular poll is indicative of the gradual increase in favorability that the pro-Palestinian movement enjoys among Democrats. In May 2022, a poll from Pew Research found that younger Americans view Palestinians and Israelis nearly equally in favorability, with 61% of Americans under 30 viewing Palestinians favorably.130 Notably, 53% of survey respondents had never heard of the BDS campaign, while another 31% had heard only a little about it.131 Demographically, atheists declared the most support for BDS among any other demographic group noted in the study.132

Resolutions both in support of the BDS movement and opposed to it have grown in prominence in recent years. In late 2019, the Trump administration issued an executive order to combat anti-Semitism on college campuses by expanding Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to include bigotry against Jews, and by adopting the “non-legally binding definition of anti-Semitism” from the IHRA.133 Section 1 of Trump’s executive order singles out the rise in “anti-Semitic harassment in schools and on university and college campuses.”134 The usage of the IHRA’s definition of anti-Semitism is significant, as it specifically cites the targeting of Israel as an example of anti-Jewish bigotry.

Figure 2.2 (Source: IHRA)135

| International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance Working Definition of Anti-Semitism and Israel-Related Examples: |

|

Definition: |

|

Examples:

|

By adopting guidelines from the IHRA into Federal regulation in order to combat anti-Semitism, the Trump administration effectively put activist groups such as SJP and supportive campus faculty and administrators at risk of penalty for violating civil rights.

The Trump administration was far from alone in tackling the BDS movement by means of legislation and regulation. Beginning in 2015, state governments began passing measures condemning the BDS movement and penalizing entities and businesses that that support the movement by means of policy.

Figure 2.3 State Governments and Anti-BDS Measures136

| State | Date | Legislation/Exec. Order (EO) |

|

April 21, 2015 April 8, 2022 |

SJR-170 SB 1993 |

|

June 4, 2015 | H-3585 |

|

July 23, 2015 | SB-1761 |

|

Feb. 16, 2016 |

SJR-6 SB81 |

|

Feb. 26, 2016 | HB-16-284 |

|

March 1, 2016 | HB-1378 |

|

Feb. 24, 2016 March 10, 2016 March 30, 2018 |

SB-86 HB-527 HB-545 |

|

March 10, 2016 | HJ 177 |

|

March 18, 2016 | HB-2617 |

|

April 26, 2016 | SB-327 |

|

May 10, 2016 March 24, 2022 |

SB-3087 SF-2281 HF-2331 |

|

June 5, 2016 | S-6378A |

|

July 1, 2016 | HB7736 |

|

August 16, 2016 | S-1923 |

|

September 24, 2016 | AB 2844 |

|

November 4, 2016 | HB2107 |

|

December 19, 2016 | HB-476 |

|

January 10, 2017 | HB 5821 and HB 5822 |

|

March 22, 2017 | Act 710 |

|

May 2, 2017 | HB89 |

|

May 3, 2017 | HF400 |

|

June 2, 2017 | SB26 |

|

June 16, 2017 | HB2409 |

|

July 31, 2017 | HB161 |

|

October 23, 2017 | EO: 01.01.2017.25 |

|

October 27, 2017 | SB553 |

|

May 22, 2018 | EO: JBE 2018-15 |

|

March 15, 2019 | HB761 |

|

August 27, 2019 | SB143 |

|

January 14, 2020 | EO: 2020-01 |

|

May 15, 2020 | HB3967 |

|

July 13, 2020 | SB739 |

|

March 17, 2021 | SB186 |

|

April 22, 2021 | SB1086 |

|

April 26, 2021 | HB2933 |

State laws can directly affect colleges and universities by opening them to potential fines and civil suits in the event that college administrations adopt resolutions passed by pro-BDS student governments. While businesses and for-profit entities are often the focus of the laws in question, the bills provide disincentives for administrators to acquiesce to activist demands. While state legislatures have passed condemnatory stances against the BDS movement, the movement itself is arguably a facet of the changing view of Israel among younger Americans who are more receptive to progressive causes.

BDS and American Jews

BDS is a fundamentally progressive movement, rather than a student-led movement devoted to Palestinian nationalism, and thrives in the progressive campus environment. Supporters of BDS are diverse, and such support includes Jews. Organizationally, Jewish groups such as Jewish Voice for Peace help spearhead anti-Israel campus activism. At the campus level, Jewish students are not inherently pro-Israel and are often involved in BDS activities.

Data on younger US Jews and their support for Israel is mixed. Nationwide, a sizable minority of American Jews support BDS. According to the findings of a recent study conducted by the Ruderman Family Foundation, 16% of American Jews support the BDS movement.137 Such findings reflect recent studies elsewhere, which have found that 70% of millennial US Jews view Israel as integral to Jewish survival.138 A recent study conducted by the American Jewish Committee about college-aged Jews found that 26% expressed willingness to forego open support for Israel in order to maintain social acceptability.139 In 2021, Pew Research discovered that only 48% of American Jews aged 18–29 described themselves as “emotionally attached” to Israel.140 The matrix of factors affecting young American Jews’ support for or opposition to the BDS movement is complex, with religiosity, political affiliation, and connection with Jewish organizations offering key indicators of levels of support.

Conclusion

In summation, the on-campus BDS movement is undoubtedly aggressive and prominent on a select number of campuses in the US. It is noticeably effective in securing the passage of student government resolutions against Israel when it has a large enough coalition of allied groups and when the endeavor is linked to broader progressive agendas. However, the ability of the BDS movement to secure policy victories from campus administrations is presently in doubt. When student governments are able to pass resolutions against Israel, they are often met with multifaceted, if disparate, roadblocks from reluctant administrators, student presidents, and popular pushback. Anti-BDS measures taken by state governments similarly complicate matters for administrations contemplating pro-BDS resolutions from student governments. Despite these victories for pro-Israel advocates, the increasing support for the BDS movement among younger Americans indicates that the anti-Israel sentiment on campus is likely having some effect on voter attitudes within younger age brackets.

Case Studies

Case Selection and Method

This section of the report closely analyzes three standout cases where BDS measures were attempted. In order to derive takeaway insights that can inform policy and pro-Israel activism strategy, key variables about the BDS movement’s success and failure need to be examined where different outcomes occurred. This section examines three universities based upon three different criteria. The first criterion is whether a college or university faced repeated BDS attempts, while the second and third criteria examine schools where BDS measures ultimately passed or failed. The schools examined below include: Columbia University, The Ohio State University, and the University of California, Riverside.

BDS Success, Failure, and Blockage

| School | BDS Attempts | No. of Passes | No. of Fails | Blocked | Pass After Failure |

| Columbia University | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Yes (Administrative) |

Yes |

| The Ohio State University | 6 | 0 | 6 |

Yes (Student Government) |

No |

| UC Riverside | 5 | 3 | 2 |

Yes (Administrative and Student Government) |

Yes |

Columbia University

Introduction

Columbia University’s student body successfully passed a BDS resolution in the fall of 2020 that called for the administration to divest the university from “stocks, funds, and endowment from companies that profit from or engage in the State of Israel’s acts towards Palestinians.”141 The successful resolution resulted from years of anti-Israel activism at Columbia, some of which pre-dates the founding of the formal BDS movement in 2004. The resolution was a campus-wide referendum in which fewer than 50% of students voted, with 61% of students favoring divestment from Israel.142 Despite its passage, the resolution was met with opposition by Columbia’s administration, which publicly rejected calls to divest from Israel.143 Far from a case of straightforward and open anti-Israel activism and pro-Israel responses from Jewish students, the history of the BDS movement at Columbia involves outside threats, harassment, accusations of censorship, and administrative distance from the movement’s successful resolution.

Origins of the BDS Movement at Columbia

The American BDS movement arguably has its philosophical and organizational origins at Columbia. One of the founders of the movement, Omar Barghouti, began his activism career at Columbia while studying engineering and protesting against Apartheid in South Africa.144 Barghouti helped found PACBI,145 as well as the BDS National Committee (BNC).146 In 2019, Barghouti was denied entry into the US when attempting to undertake a speaking tour at NYU and Harvard.147 While he was ostensibly denied over an unspecified “immigration matter,” then-House Representative Lee Zeldin noted that the “rise of anti-Semitism and anti-Israel hate throughout the world” justified the move.148 Barghouti was also denied entry to a Labour Party conference in Britain several months later under a similar rationale.149

Columbia is perceived as one of the most anti-Semitic colleges in the US. In 2014, the David Horowitz Freedom Center, a conservative think tank, published a report outlining anti-Semitic activity on American college campuses that gave Columbia the worst ranking in the country for hostility toward Jewish students.150 Aside from hosting an aggressive SJP chapter and talks by figures such as Omar Barghouti, the report noted how the prominent presence of anti-Semitic faculty such as Rashid Khalidi and Joseph Massad contribute to an anti-Semitic campus environment.151

Khalidi, a professor in Columbia’s history department, has his own controversial past. After obtaining his doctorate from the University of Oxford in 1974,152 Khalidi was involved in Palestinian politics and is believed to have worked for the PLO’s press agency in the early 1980s.153 Another Columbia professor in the university’s Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies progam, Joseph Massad, has held anti-Semitic talks using his academic position as a platform. In 2002, one of Massad’s talks was titled “On Zionism and Jewish Supremacy.”154 Massad’s other talks, on themes such as “Zionist-Nazi Collaboration” and the “Anglo-American Gay Agenda,” carry similar anti-Semitic tropes. In 2013, Massad wrote a piece published in Al Jazeera asserting that Nazi Germany was “pro-Zionist.”155 Prior to the BDS movement’s formal founding, Massad was investigated in 2002 for intimidating a Jewish student.156 Despite years of controversy over the anti-Jewish sentiment at Columbia, both professors retain their positions on campus. A third Columbia professor of note, Nadia Abu El-Haj, was the center of controversy in 2007 while seeking tenure due to her anthropological work accusing Israel of systematically doctoring and destroying archaeological evidence to legitimize the existence of a Jewish state.157 Columbia’s culture of anti-Semitism is promoted in part by university faculty.

As a specific brand of activism, the BDS movement at Columbia came to the fore in 2010 in conjunction with SJP’s “Israel Apartheid Week” (IAW). In March 2010, the Columbia SJP chapter (CSJP) launched a series of events for IAW that included a “mock Apartheid wall,” a talk with a producer from the organization Democracy Now!, and a demonstration at New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel in protest of the “Friends of the Israel Defense Forces” annual fundraiser.158 What is notable about CSJP’s first major salvo of activism at Columbia is that it included an array of progressive organizations that reached beyond the confines of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.159

On March 3–4, 2010, the IAW included events that framed the BDS movement as part of a wider postcolonial struggle. One workshop titled “Occupation and Resistance from Palestine to Turtle Island” included self-described “strategizing with 7th Generation Indigenous Visionaries-Students,” encompassing Native American activists, while the workshop the following day featured the same theme, but included former activists from the boycott against South Africa in the 1990s.160 The protest at the Waldorf Astoria demonstrates the same dynamic of broadening the BDS movement beyond its issue-specific base, including groups such as CODEPINK, the Center for Immigrant Families, the New York chapter of the National Lawyers Guild, and American Jews for a Just Peace.161 One of the main groups sponsoring Columbia’s larger IAW events, such as themed talk on “Indigenous Struggle” and the protest at the Friends of the IDF dinner, was WESPAC, a group known for funding the BDS movement.162

In April 2010, in commemoration of the “Nakba” (“catastrophe”) of the creation of Israel in 1948, CSJP reified its hardline stance by asserting its rejection of “normalization” with Israel.163 In its official rejection of normalization, CSJP adopted the standard set by PACBI and the BNC.164 Translated from Arabic, SJP’s rejection of normalization consists of:

Participating in any project, initiative or activity whether locally or internationally that is designed to bring together-whether directly or indirectly-Palestinian and/or Arab youth with Israelis (whether individuals or institutions) and is not explicitly designed to resist or expose the occupation and all forms of discrimination and oppression inflicted upon the Palestinian people.165

From its first forays into activism in 2010, CSJP brought regular demonstrations both on and off campus. The 2010 protest at the Friends of the IDF dinner set a precedent where on-campus activism involved the greater public square. In May 2010, CSJP protested in Times Square in reaction to Israel’s storming of the Mavi Marmara, a Turkish ship seeking to land in Gaza.166 In fall 2010, other demonstrations included a “mock Israeli checkpoint” in front of Columbia University’s Low Library.167 The checkpoint included CSJP members depicting Israeli soldiers harassing and humiliating other members performing the roles of Palestinian civilians.168

While the first year and a half of SJP’s work at Columbia consisted of establishing a record of educational activism, the chapter facilitated and hosted the National Students for Justice in Palestine Conference at the university in 2011.169 The goals of the conference focused on developing the pro-Palestinian movement and a “particular (but not exclusive) emphasis on Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS).”170 The conference culminated with nearly 400 students and more than 130 different student groups in attendance.171 The conference also began internal SJP dialogue about formulating the group’s national organization.172 By 2014, CSJP’s efforts lead to conflict with Jewish students on campus and official calls for divesting from Israel among university faculty.

Anti-Israel Activism on Campus and Divestment Efforts (2016–2021)

In 2013, BDS efforts at Columbia reached a new level of intensity when more than 100 faculty from the school, and faculty from Barnard College, demanded that the university’s pension fund, TIAA-CREF, divest from companies viewed as affiliated with Israeli security operations.173 Notably, the faculty directly petitioned Roger Ferguson, CEO of TIAA-CREF, to divest from five specific companies deemed to be “supporting human rights abuses.”174 These five companies were Elbit Systems, Motorola (due to its Israeli subsidiary), Hewlett-Packard, Veolia, and Northrop Grumman.175

While CSJP applauded the faculty for pressuring the pension fund, it also endorsed the prison divestment movement in the United States. In a move of economic activism beyond the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, CSJP demanded that Columbia University divest from portfolio holdings worth $8 million from the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), and demanded that the university direct its fund managers to pressure banks, financial firms, and venture capital groups to divest from CCA.176 Along with its endorsement of the prison divestment campaign, CSJP demanded that the university make its investments transparent to the student population.177

Far from ineffective, CSJP’s efforts, and those of other left-wing campus groups, culminated in Columbia divesting from CCA in 2015. Indeed, Columbia was the first university to follow through on such economic activism and divestment.178 Columbia’s president, Lee Bollinger, declared, “the issue of mass incarceration in America weighs heavily on our country, our city, and our University community.”179 In contrast to his tacit support for prison divestment, Bollinger declared opposition to divestment from Israel in 2020, when he asserted that the university “should not change its investment policies on the basis of a political position unless there is broad consensus within the institution that to do so is morally and ethically compelled.”180 It is noteworthy that CSJP’s first major drive to secure a BDS victory at Columbia took place in the 2016–2017 academic year, shortly after the school decided to divest from prisons. For reference, Columbia also divested from coal in 2017.181