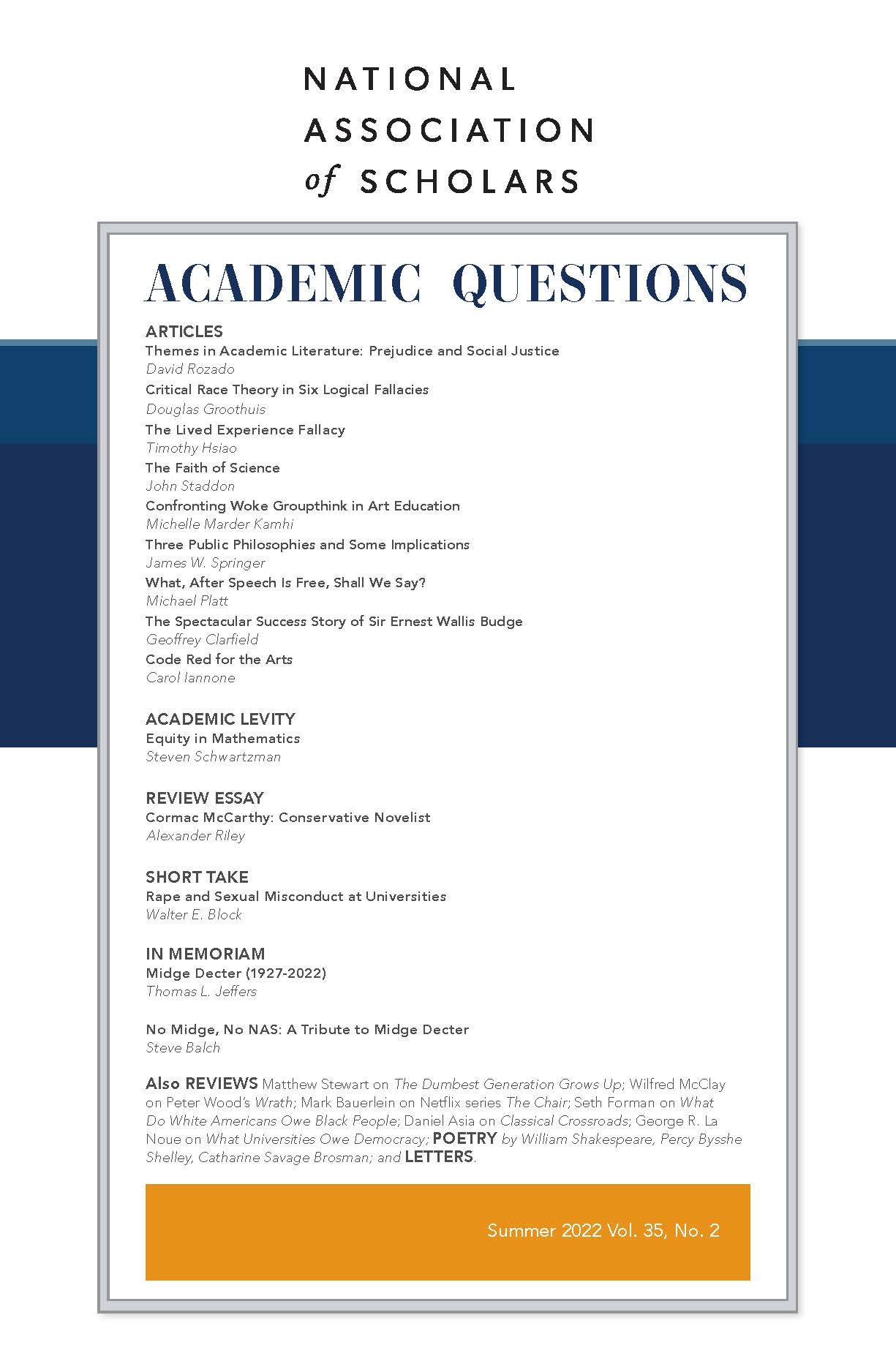

Wrath: America Enraged, Peter W. Wood, Encounter Books, 2021, pp. 256, $24.49 hardbound.

Wilfred M. McClay is the Victor Davis Hanson Chair in Classical History and Western Civilization, and Professor of History, at Hillsdale College. He gave the keynote address at the Thirtieth Anniversary Conference of the National Association of Scholars.

Peter Wood has undertaken something quite exceptional, even daring, in this book. It is a bit of a high-wire act, and I have to say that there were times when in reading this most unusual study I felt the way one feels when one watches an acrobat high above the floor of the arena, especially at those moments when he is adjusting and compensating to maintain his balance. It’s not that Wood isn’t always in masterful control of his unruly and temperamental subject. But I often found myself leaning this way and that, in body-English sympathy with the performer, hoping to provide him that slight edge from the audience that makes the difference and keeps him from tipping over and plunging down into the net. Which is another way of saying that Wood draws you in, and makes you a part of his quest.

That quest matters profoundly, even if its essential character and objectives are elusive at times, hard to define and hard to frame. But this is precisely a sign of the book’s importance. I am reminded of a saying by one of my graduate-school teachers, who formulated something that he called (I’ll give him a different name) Smith’s Law: the more precisely a question or research problem can be stated, the more trivial the answer will be. Oddly enough, Professor Smith was himself an exponent of highly technical and quantitative research; he was good at asking precise questions, and using sophisticated social-scientific methods to answer them precisely.

But he was also, like Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry, a man who knew his limitations. He knew that the world needs other kinds of works: ones that are willing to speculate, to take chances, to draw on a long line of credit in order to stimulate and provoke. Wrath: America Enraged is such a book. Its central contention is a proposition, or rather a set of propositions, that are profoundly important, and yet defy easy formulation.

What Wood is trying to do is get to the heart of the growing role of anger in our culture, to criticize it in some ways and yet to legitimate it in others, and give us clues as to how it might be refined into something essential. It’s a subject he visited once before, in his 2006 book A Bee in the Mouth: Anger in America Now, but it’s clear that he regards our country’s current circumstances as sufficiently altered in the decade and a half since then, and the problem sufficiently deepened, to require that the subject be revisited. He makes a complicated argument, and in the end, its persuasiveness to readers will depend on the degree to which it helps us to think differently about the cultural and political challenges that we face, in what seems increasingly to be a disintegrating society.

To begin with, there is the problem that haunts all cultural generalizations: how does one go about measuring the extent of a given society’s emotional makeup, and compare it to the emotional quotient of other times? Do such comparisons even make sense? Or are they little better than the cartoonish semi-journalistic periodizations—the Gay Nineties, the Roaring Twenties, the Me Decade, and so on—that pass for understanding? How do we compare the anger quotient of today’s America to the anger quotient of yesterday’s, or nineteenth-century America, or some other country or time? This would seem to be just the kind of undertaking that Smith’s Law would warn one against even attempting.

Add to that the difficulty that “anger” is not a single clear and undifferentiated thing, but a complicated compendium of emotions, that encompasses everything from mild annoyance to homicidal fury—well, then it seems clear that you have set yourself a problem of near-indecipherable intricacy, when you set out to generalize about anger in America at the present moment.

These criticisms can all be easily argued. And yet it is precisely the unwillingness to tackle such tangled issues that has made so much modern historical and social-scientific writing so arid and listless. Wood has a very precise and orderly mind, but that has not stopped him from venturing forward boldly with his project, precisely because the subject is too important not to be addressed. The result is an effort that is both credible and full of potential further insight. If one can accept the foundational idea that our times are peculiarly marked and animated by rising anger, and by anger of a particular kind, then there is much else that flows from that assumption.

Let’s begin with the word wrath. Wood distinguishes between wrath and garden-variety anger, the former being a form of high-octane rage that is more expansive, more comprehensive, and more unappeasable than mere anger. Anger is something one has, but wrath consumes us, becomes a part of our being, threatens to swallow up our entire identity. We have all had the experience of listening to a rant from a man or woman who is so completely under the spell of some moral conviction or ideological fantasy or conspiracy theory or other perceived existential threat to their dignity that, when the moment arrives for them to display, they swell with a sense of perfect righteousness, of perfect confidence in the righteousness of their plaint. It can be both impressive and appalling to witness such displays. The speakers are making an emotional move that draws together all their life’s troubling complexities, all the burdens of their anxiety and shame and guilt and fear, and offloads them into the container of this grand rage—which, like an enormous and continuously burning bonfire, offers the possibility of purification, sanctification, complete moral release, and overcomes all need for argument, data, proof, and the requirement to listen to the other side of things. Because in fact there is no other side; there can be no other side; and if you disagree you are not merely wrong, but a criminal, who acts in bad faith and deserves to be silenced.

We use the word “woke” as a shorthand for our current experience of this fanatical disposition. But that somewhat anodyne word perhaps understates the weird combination of pathology and seriousness—and its obvious potential for violence—with which we are increasingly faced. Wrath is not a new word in the American vocabulary; we know it through the Bible’s descriptions of the end times, incorporated into the words of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” in which God is “trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.” In the past wrath has generally been associated, rightly or wrongly, with divinely ordained causes. In a culture in which the idea of God’s providence has but a weak hold even on the mind of those who believe in Him, and in which religion itself is often a principal object of wrath, that may no longer be the case.

The potential for carnage, and for the wreckage of institutions and procedures that are fundamental to the conduct of liberal democracy, is becoming immense. And when wrathful figures from our past, such as the murderous abolitionist zealot John Brown, are exhumed and elevated into culture heroes because of the diamond-like purity of their intentions, as opposed to compromisers like Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, our democracy is in trouble.

Let me provide a few recent examples of present-day wrath, if examples are needed. As I write these words in early June of 2022, Americans are trying to come to terms with fresh news about an attempted assassination of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, even as the Department of Justice seems to be making no effort to enforce Federal laws designed to protect the Justices. Threatening protestors have gathered around the homes of conservative Justices whom it is thought will vote “wrongly” on the Dobbs abortion case currently before the Court.

In early June, a retired Wisconsin circuit judge named John Roemer was shot and killed at his home in Wisconsin in what has been described by officials as a “targeted” attack against people who were “part of the judicial system.” There has been little if any sustained reaction to these horrors, and the Washington Post relegated the Kavanaugh story to page A-10 the day after the news broke.

Or consider the case of Dr. Preston Phillips, a surgeon who was gunned down on June 2nd along with three others at Saint Francis Hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma, by a wrathful former patient who found himself in pain after a May 19th back operation. A letter recovered from the gunman made it clear "that he came with the intent to kill Dr. Phillips and anyone who got in his way," Tulsa Police Chief Wendell Franklin said. "He blamed Dr. Phillips for the ongoing pain following the surgery."

These examples taken from just a few days could be multiplied, but they serve to amplify Wood’s point: there is something distinctive about these acts, a pattern in which a grievance is taken up, and the sheer emotional size and intensity of the grievance establishes the fact that there can be no justifiable limit to the extent of retribution for it. Yet the catalyzing event can often be something pathetically trivial. Wood begins his book with an example of a 2021 Pennsylvania incident in which a quarrel over snow-shoveling led to the death of three neighbors. A great many of us have experienced or witnessed “road rage” incidents that begin with something almost unimaginably small, and yet the bottled-up rage that seems to be resident in so many of us these days cannot resist the chance to burst forth, and expend itself cathartically upon whatever hapless object appears in its path.

As Wood puts it, dryly, “the angri-culture is, in this sense, an overthrow of older ideals of temperance and self-control.” In a culture that has abandoned all regard for the moral value of restraint, and distrusts old virtues such as modesty and politeness as forms of genteel lying, anger is authenticating; that is why everyone, from politicians to otherwise demure soccer moms, feels compelled to add the once forbidden modifier “fucking” to intensify every noun and every verb in every statement in which one is stating a passionately held view (e.g., “There is no fucking way I am going to do that!”) There is an implicit intransigence, bordering on violence, in this way of expressing oneself, a warning that to disagree means entering into a realm in which reasonable discourse has no standing and no force.

Instead, we have enthroned passion as our psycho-spiritual God-term. And this is not just a feature of the therapeutic ethos at bicoastal prep schools. I remember visiting a small and putatively very conservative Catholic college several years ago, and seeing lovely banners all over campus proclaiming: “Find your passion at St. X’s!” Of course, I knew what they meant; and every parent wants for his child to find some interest in life that will mobilize his energies and direct them toward some constructive purposes, and every parent (and every teacher) hopes that college will be the means of that discovery. But I was too polite to ask my hosts: what about finding reason? Or faith? Or virtue? Or the capacity for devotion and sacrificial love? If St. X’s wants to stand against the angri-culture, as presumably it does, shouldn’t it promote these things? Of sheer passion, we would seem to have more than enough.

And one might well assume that this is where the argument of Wood’s book is taking us. As the predictably banal Peggy Noonan puts it in a recent column, entitled “The Boiling Over of America”: “The lesson of this political moment: Don’t be radical, don’t be extreme. Our country is a tea kettle on high flame, at full boil. Wherever possible let the steam out, be part of a steady steam release before the kettle blows.”

That is the counsel of the complacent. But what if there are instances in which the anger has ample justification? What if the problem with wrath is only partly due to the intransigence it induces? What if the kettle needs to blow? Wood’s book does not make the mistake of treating psychology as an independent variable, and wrath as nothing more than a pathology brought on by miseducation and self-indulgence.

Hence the book never degenerates into a sermon against kettle-blowing passion. Just when you think he’s about to make that move, he turns, and makes it clear that this is not a book directed against wrath per se, but that wrath is a symptom as well as a cause, and people can be wrathful for good reason. He wishes to give wrath its due, and argues that a great many Americans are consumed with a wrath that is, despite its occasional ugliness, justifiable. It represents their response, often inchoate but entirely genuine, to the takeover of the American economy, society, culture, and politics by a new ruling class that has disempowered them, made a mockery of the electoral system, and seeks to erase every element of their traditional culture and make them wards of the state. About these things Wood is not neutral.

So in the end, the problem of wrath becomes more one of redirection than suppression. Of harnessing it. Many of the most reasonable among us don’t “do wrath” well, because we are . . . reasonable, reticent, temperate, sane. We don’t do well living on a diet of righteous indignation. But circumstances are different, and the importance of the things that are at stake mean that we have to be willing to credit wrath and recruit it to the cause at hand, without letting it take command. That is a difficult task. But like the charioteer in Plato’s Phaedrus, we must learn anew how to command the dark horse of passion in order to save what is precious to us. So concludes Wood in this unusually thoughtful, subtle, wise, and challenging book.