A Is for Activist is a little square book (5.5 inches x 5.5 inches) by Innosanto Niagara, an Indonesian-born American immigrant who has worked as a free-lance designer since the 1980s while devoting himself to “activist organizations and campaigns.” Most of his published work is aimed at young children. A Is for Activist is an alphabet book that first appeared in 2013, and commences:

A is for Activist.

Advocate. Abolitionist, Ally.

Activity answering as A call to Action.

Are you An Activist?

The accompanying illustration shows three cadres perhaps on recess from kindergarten each clutching their little protest placards. Niagara proceeds through the alphabet with colorful images to enhance his vocabulary lessons. Most of the words are social justice exhortations, but some help young minds to focus their opprobrium. C is not only for Co-op, but also for “Corporate vultures.”

I picked up my copy of A Is for Activist at an “independent bookstore” in Sante Fe a while back, and it has stood me in good stead as I attempt to read the works of many contemporary academics. O is for:

Open minds Operate best.

Critical thinking Over tests.

Wisdom can’t be memorized,

Educate! Agitate! Organize!

Z, in case you are wondering, is for Zapatista.

Recently the New York Times polled 503 “novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics, and other book lovers” to compile a list of “The 100 Best Books of the 21st Century.” As a pretty avid reader, I was eager to see what made the cut. A Is for Activist is not among the favored one hundred, but the spirit of activism, political dissent, and alienation from social conventions is salient. The best books include:

- Detransition, by Torrey Peters, 2021, a novel about a “messy triangular romance— between two trans characters and a cis-gendered woman.”

- The New Jim Crow, by Michelle Alexander, 2010, a polemic on how blacks suffer from “systematic legal prejudice,” as evidence in mass incarceration.

- Nickel and Dimed, by Barbara Ehrenreich, 2001, in which the author tries out and reports on life in a variety of low-wage jobs including “waitress, hotel maid, cleaning woman, retail clerk,” all of which illustrate the essential unfairness of American capitalism.

- Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates, 2015, in which the author instructs a young relative on the perils of living in America “within a black body.”

- Fun Home, by Alison Bechdel, 2006, a memoir in the form of a book-length cartoon about the author’s self-discovery as a Lesbian, the family funeral business, and her father’s suicide.

- Citizen, by Claudia Rankine, 2014, prompted by the death of Trayvon Martin, “lays out a damning indictment of American racism through a mix of free verse, essayistic prose poems, and visual art.”

- Evicted, by Matthew Desmond, 2016, “crystallizing the ills of a patently unequal America—here it’s the housing crisis, as told through eight Milwaukee families.”

A fair number of the Times’s twenty-first century “best books,” however, deserve the accolade. Here are works by Denis Johnson, Alice Munro, Cormac McCarthy, Kazuo Ishiguro, Hilary Mantel, Jonathan Franzen, and Marilynne Robinson.

Other books fall into a category I would call strenuously pretentious such as The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis, the doyen of micro-fiction, known for stories that consist of one short paragraph or a single terse sentence. Jon Fosse’s Septology also fits this niche but in the opposite direction. Fosse is a Norwegian writer whose Septology consists of a single sentence stretched over 700 pages. Ben Lerner’s 10:04 is yet another version of oddity for oddity’s sake. Lerner creates an image of himself that may or may not be the real fellow struggling to write the book in hand.

The Times’ list includes other books that appear to be little more than yesterday’s cut flowers, now wilted. And a great many of the books ring the chimes of identity politics. Twenty-four of the selections are books about race and the black experience in the U.S. including Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped, Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, and Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of other Suns.

There are also generous helpings of books on the travails of other minorities: Vietnamese, Dominican, Korean, etc. and thirteen of the books are translations. Fiction dominates but the nonfiction includes the fourth volume of Robert Caro’s massive biography of Lyndon Johnson, Svetlana Alexievich's Secondhand Time an oral history of the fall of the Soviet Union, Lawrence Wright’s The Looming Tower: Al-Qaida and the Road to 9/11, and Tony Judt’s Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945.

It is arresting to see a handful of authors claim multiple spots on the list: Alice Munro, Denis Johnson, Philip Roth, Zadie Smith, and Hilary Mantel, each with two books, and George Saunders and Jesmyn Ward with three each.

The editors and authors they consulted may have passed over A Is for Activist, but they provide a rich harvest of what can best be called grievance literature, both fiction and nonfiction. This is not necessarily a complaint. Literature over the centuries has often dealt with social grievances, and expressing unhappiness at injustice and offense is—or can be—a worthy literary pursuit. But it isn’t the whole ball game.

Where are the twenty-first century literary works that trade in themes of hardship mastered, friendship and enmity, obstacles overcome or not, self-discovery eventuating in rue or satisfaction, virtue vindicated or overwhelmed? Some of these matters make fugitive appearances on the list, but on the whole, the Times’ enunciates the darkness of an age baked in its own dissatisfactions and pleased mostly with the opportunity to complain. When they aren’t complaining, they are often touring the outer edges of things. George Saunders, for example, is extolled by a Times’ reviewer for his “exuberantly weird stories.” He is best known for his novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, which depicts the sixteenth president visiting the Tibetan realm between life and death to commune with the spirits.

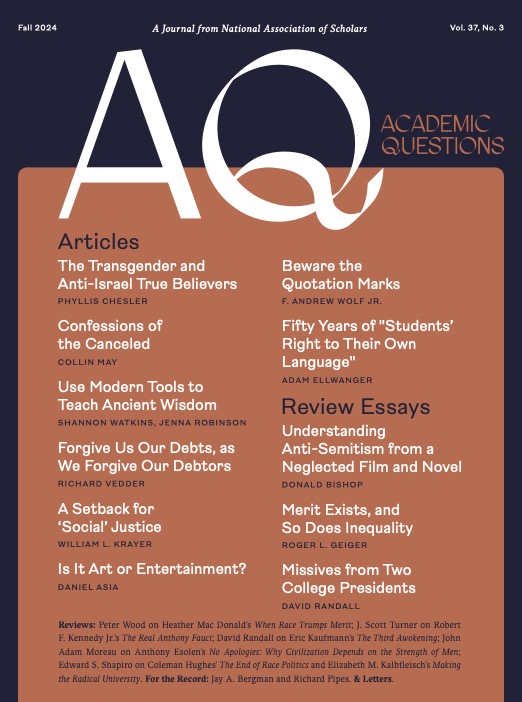

The New York Times, of course, is a voice of cultural authority, but so is, in his way, Innosanto Niagara. People tend to be generous in letting others know what really counts. “Educate! Agitate! Organize!” says Niagara. Mindful of this counsel, we dedicate this issue of Academic Questions to the debates over the sources of real and ersatz authority.

First we have an essay by Phyllis Chesler, psychotherapist, professor emeritus of women’s studies, and well-known second-wave feminist. Chesler explores the commonalities of transgender activists and anti-Israeli extremists. Both she says dispense with the authority of history in favor of narratives of their own invention. As Niagara put it, “N is for NO. No to what must go!” But, “Yes to what we want.” That simplifies things.

Collin May in his essay, “Confessions of the Canceled,” delves into the odd phenomenon in which the targets of cancel culture often confess their guilt. Why did the accused in Stalin’s show trials so reliably declare that they were indeed enemies of the state? And why do so many academics who are plainly innocent of the “hate crimes” charged against them capitulate to their tormentors? C is for co-operation.

Shannon Watkins and Jenna Robinson in “Use Modern Tools to Teach Ancient Wisdom,” walk us back to the heated dispute in the eighteenth century between those who upheld the authority of the ancient texts, and those who declared a new regime of modern science. Jonathan Swift depicted the confrontation as a literal “Battle of the Books” in the preface to A Take of the Tub. Watkins and Robinson call for an armistice in light of greater dangers. “U is for Union.” But probably not that union.

This issue of Academic Questions has more than an alphabet-full of authoritative articles, so at this point I will compress. Richard Vedder, professor of economics and NAS board member, elucidates the vexed issue of massive student debt. William Krayer offers a new look at the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Students for Fair Admission vs. Harvard and the University of North Carolina. Krayer reminds us to keep our eye on the “separate but equal” ball played by the universities to justify racial preferences. NAS board member and professor of music Dan Asia observes that the newly popular spectacle of “immersive experiences” in famous works of art is mostly testimony to contemporary narcissism.

F. Andrew Wolf, Jr., a retired colonel in the U.S. Air Force, examines how many academic economists have been seduced by sirens of postmodernism. One slant is that neo-liberal economists have ignored the harm of globalization and immigration to the American middle-class.

Adam Ellwanger pricks the balloon of the writing professors who champion the idea that students have a “right to their own language.” The result, of course, is instruction in composition that leaves the students bereft of ability to get their ideas across to anyone else.

Donald Bishop, a foreign service officer, offers a fascinating sidelight on the October 7 attack on Israel. He examines Nazi antisemitism as depicted in a novel from 1938 and the 1940 Hollywood adaptation, The Mortal Storm. The pre-Holocaust view of what Hitler was about is vivid.

Roger L. Geiger reviews two books on the nature of “merit” that take opposing views on whether we should expand or contract “meritocratic systems.” David Randall reviews two memoirs by former college presidents who, besides extolling their own accomplishments, explain how they each played the racial spoils sweepstakes and loaded their institutions with intellectually vacuous identity studies programs.

This issue of Academic Questions also includes “How the Intelligentsia Poisoned Modernity,” an extract from the late Richard Pipes’ The Russian Revolution (1990). Pipes’ son, Daniel, serving as executor of his father’s estate, spotted the stand-alone essay, and thinking it pertinent to the world today, offered us the opportunity to republish it. NAS board member Jay Bergman, himself an expert on Soviet matters and the Russian revolution, penned an introduction.

We also have a host of other book reviews. I review Heather Mac Donald’s When Race Trumps Merit, NAS Director of Science Programs J. Scott Turner reviews Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s The Real Anthony Fauci; David Randall reviews Eric Kaufmann’s The Third Awokening; John Adam Moreau reviews Anthony Esolen’s Of Men and Manliness. (Having Phyllis Chesler and Anthony Esolen in the same issue is testament to AQ’s catholicity—albeit they are at opposite sides of the volume.) Edward S. Shapiro reviews Coleman Hughes’ The End of Race Politics. Shapiro also reviews Elizabeth M. Kalbfleisch’s Making the Radical University, which is an attempt to justify the domination of contemporary American higher education by the left. A is for activism, after all.

I have been told by a few stalwart souls that they read Academic Questions cover to cover. I admire that devotion, and I guess I am one of the faithful as nothing reaches publication in this journal without my having read it three or four times. This is a sacrifice I willingly make to the cause of restoring legitimate intellectual authority in the commonwealth of letters. But that task is necessarily a collective enterprise. None of us can hope to read all of the New York Times’ “100 Best Books of the 21st Century.” And without having done so, our individual authority to pass judgment on the Times’s judgment or the judgments of the authors they consulted is imperfect.

I am probably not going to read Detransition by Torrey Peters, though I’ve made my way through Nickel and Dimed and Between the World and Me. I doubt I will get to Ali Smith’s How to Be Both, and may thus miss whatever delights are to be found in its “passionate, dialectical critique of the binaries that define and confine us.” But I don’t reject out of hand reading books or authors that I suspect I’ll find uncongenial or irritating. We ought to be willing to go places, do things, and entertain ideas that summon our attention and may require a temporary suspension of doubt. We find our way to real authority by testing our own convictions as well as those of others. Q of course is for Questions, Academic Questions.

Peter Wood is president of the National Association of Scholars and editor-in-chief of Academic Questions.

Photo by Artem Maltsev on Unsplash